by Stephen Wass

The Citadel, view from Mount Batten to the south east

As one of Britain's major naval ports Plymouth has had defences since the late medieval period. In 1859 under the direction of Lord Palmerston a Royal Commission was undertaken to consider the defences

of the United Kingdom largely because of the perceived threat of an attack by the French. As a result the period between 1860 and 1869, when a second commission was appointed to review progress, a programme of fortress design and construction unprecedented in its scale and cost gripped the south coast.

The purpose of this preliminary study is to investigate the defences within their landscape setting and in particular some of the lesser works such as connecting ramparts and ditches and the covered military ways. It is also instructive to consider questions of access, visibility and use both in the original context of the works and particularly how they are presented to the inhabitants of and visitors to the city. As far as I am aware this complex of defensive works is unique in this country. The starting point was to map the fortifications using modern Ordnance Survey maps and aerial photographs as well as consulting historical maps many of them made available on Steve Johnson's Cyberheritage pages. These original plans may be revealed by running the mouse over the redrawn versions. Following this initial piece of digital prospecting a three day visit was made in April of 2010 when as far as possible sites were visited photographed and videoed, sections measured and drawn and the connecting linear features identified and recorded. In addition a number of conversations were had with local residents and visitors which provide the material for the brief remarks below. Given difficulties of access some interesting techniques were resorted to for surveying the remains about which a separate note follows.

DISCLAIMER: This is not really my subject, I consider myself to be a dirt based archaeologist and so I appreciate that my knowledge of nineteenth century gunnery and fortifications is limited and it is likely therefore that I have unwittingly made a number of mistakes, not least in mixing up casemates and casements - now corrected! It is also important to note that I have done virtually no work to consult contemporary documents relating to the planning and construction of these works. However, the great advantage of publishing on line is that it is easy to rectify mistakes and I would, therefore, be grateful for any amendments or corrections that anyone feels moved to send in. Emails please to editor@polyolbion.org.uk Most of the sites discussed present many dangers to the unwitting explorer. Readers must not assume that places mentioned in the text are available for public access, I have tried to give some indication for each monument what the access issues are. Despite the use of material from various urban exploration groups this site does not endorse the committing of acts of trespass whilst at the same time admitting a sneaking admiration for those who do! I also apologise to those whose displays cannot handle the wide screen format, sorry but I just love the big picture. |

The defences of Plymouth can be divided up into a number of sectors or regions. They are:

The Northern Line

The Staddon Line or Eastern Defences

The Western Defences

(Coming next year)

The Citadel

Other City Defences

(Coming next year)

The Devonport Lines

(Coming next year)

The Staddon Line or Eastern Defences

The Western Defences

(Coming next year)

The Citadel

Other City Defences

(Coming next year)

The Devonport Lines

(Coming next year)

Observations on the current condition of Plymouth's Fortifications

Clearly the whole span of the defences of Plymouth represent an extraordinary collection of monuments and an associated military landscape. Remarkably despite extensive housing development, especially along the northern line across what was originally open farm land much has survived of the lesser earthworks. Unfortunately it is equally obvious that despite the statement by the city council (see below), there are no evident signs of a co-ordinated response to explain, make accessible and preserve these sites in context. The view that the local population remain largely in the dark about these matters and the frustration felt by those who do show an interest is well expressed in a blog entry by 'GeorgieKirrin' who comments:

"We live in a city rich in history; one that over time has played vital roles in exploring, conquering and defending. Yet even locals struggle to point out a handful of the countless landmarks and buildings that rot away in hedgerows or fall prey to private ownership with no hope of preservation. There are some 150 military fortifications across the city and surrounding area, we pass them daily. Just a simple 3 mile drive West along Crownhill Road and Fort Austin Avenue takes us past Ernesettle Battery, Agaton Fort, Knowle Battery, Woodland Fort, Crownhill Fort, Bowden Fort, Forder Battery, Eggbuckland Keep and Austin Fort. But how many of us can say they have glimpsed anything more than a hint of the imposing limestone walls often barely visible through a cloak of undergrowth? It drives me to Victor Meldrew-ism that we city-folk don’t have the opportunity to explore and experience for ourselves some of these elusive and romantic historic monuments."

It is easy to see why we are confronting hard issues here. The technical problems of conserving such complex structures are formidable and the sheer scale of the surviving works offer a daunting prospect but more could and should be done. That little is being undertaken suggests that the remains have very little value in the eyes of the public and by extension of politicians. Having toured the area extensively it is hard to recall a major set of monuments with so low a public profile, apart from individual name boards the only informative notice discovered in whole of the Northern and Staddon lines was a remarkably smart one in granite at Mount Batten.

There are of course several reasons for this ‘low profile’, one of them curiously enough being the physical ‘low profile' that artillery fortifications in the nineteenth century were forced to adopt. Despite being huge structures the forts hunker down in the landscape and rapidly become invisible. Many sites from a distance simply appear as isolated patches of Woodland, they are easy to ignore unless one’s attention is drawn to them and there is precious little to do this. The authorities who promote tourism in Plymouth make very little mention of the sites. Crownhill is an exception but it hardly qualifies as an accessible venue for casual visitors. There is not even an information panel on display outside a site which must, one way or another, have attracted considerable public funding for its restoration.

The general lack of information was reflected in the many conversations I had with residents during my tour. Apart from one extremely knowledgeable enthusiast met in St. Budeaux’s churchyard most people were confused about purposes, functions and dates, mistook artificial features for natural ones or were simply unaware of what was around them. Of course there is little to inspire interest or excitement in the defences since the story they tell whilst a salutary one offers very little that is exciting or romantic. The simple fact is that like so much military spending the works were obsolescent before the country had finished paying for them. In most cases they were never armed and they played no part in significant sieges or dramatic battles. A number of cases are high lighted of accounts, some of them quite moving, of the role some of the forts played during the two world wars but the stories are peripheral to the grand sweep of history.

So

the fortifications of Plymouth remain largely invisible both within the

landscape and within the historical narrative. Worse still when the

public do stumble across these sites with a few honourable exceptions

the messages they receive are negative ones. Looking specifically at

the Northern Line the sequence we have can be tabulated thus:

| Site | Access | Positive Features | Negative Features | Scheduled Monument | On English Heritage 'At Risk' register |

| Ernesettle | None | Secure | Some tipping over the fences, forbidding signs and fencing | Yes | No |

| Agaton | Limited | Interior neatly maintained | Given over to testing of vehicles, tipping in ditches | Yes | Yes |

| Knowles | Limited | Educational setting | Poorly maintained | Yes | Yes |

| Woodland | Open | Use as community centre, some clearance | Some vandalism and tipping | Yes | Yes |

| Crownhill | Limited | Very well maintained | No information about a major monument | Yes | No |

| Bowden | Limited | Attractive garden centre | Hard to see the fort for the plants | Yes | No |

| Buckland | Limited | Well maintained | Cluttered with ancillary buildings | Yes | Yes |

| Forder | None | BT Station, secure | Very overgrown | No | No |

| Austin | Limited | Council depot some maintenance | Dominated by council activities | Yes | Yes |

| Deerpark | Open | Landscaping within housing estate | Uncared for, litter and tipping | No | No |

| Efford | None | Location dominates E approach to city on A38 | Overgrown, Under private occupation | Yes | Yes |

| Laira | Limited | Some attempts at conservation | Used as equipment store limits access, surrounding area unkempt | Yes | Yes |

Plymouth City Council's own 'Buildings at Risk Register'. compiled in 2005 can be accessed

here, a useful document in terms of setting a context for the needs of

these military sites as compared with buildings in the rest of the city. Here is an extract from the English Heritage Buildings at Risk Register for 2009.

Visually most sites and their surroundings are plagued by litter, graffiti and vandalism and apart from Crownhill and Bowden present an unattractive face to the public. The Citadel is a special case, well maintained with a readily accessible exterior this is a major monument of international significance yet apart from a few ancient 'Ministry of Public Buildings and Works' plaques there is nothing in the way of information panels or labeling anywhere to be seen on such a prominent and touristic location. Why? Why not?

Let us now consider the statement by Plymouth City Council.

Statement by Plymouth City Council from their web site:

"The extent of care or repair ideally needed for each of the forts varies greatly from one site to the next. In fact the range of uses that these structures have been put to is diverse and each type of use can bring its attendant problems, in addition to the day-to-day maintenance required to keep them functioning as useful buildings. All of the forts are in beneficial ownership of one kind or another, whether this be public or private. However an overall management strategy for their well being based upon recognition of their original purpose and the common management problems encountered would be a step forward.

In a recent characterisation study of Plymouth undertaken on behalf of English Heritage, the Palmerston Forts, particularly those of the north east defences, were recognised as contributing towards the development of the neighbourhoods to the north of the city, due to the existence of the major east/west route created by the linking military road. This study has raised the profile of the Palmerston forts and has led English Heritage to call for more detailed studies of the contribution that the forts make to the heritage of northern Plymouth and to the city as whole, and to their consideration within local area action plans.

Plymouth City Council intends to follow up on the renewed interest in the Palmerston Forts and their unifying heritage value, and intends to promote policies for their increased recognition within the emerging Local Development Framework"

"The extent of care or repair ideally needed for each of the forts varies greatly from one site to the next. In fact the range of uses that these structures have been put to is diverse and each type of use can bring its attendant problems, in addition to the day-to-day maintenance required to keep them functioning as useful buildings. All of the forts are in beneficial ownership of one kind or another, whether this be public or private. However an overall management strategy for their well being based upon recognition of their original purpose and the common management problems encountered would be a step forward.

In a recent characterisation study of Plymouth undertaken on behalf of English Heritage, the Palmerston Forts, particularly those of the north east defences, were recognised as contributing towards the development of the neighbourhoods to the north of the city, due to the existence of the major east/west route created by the linking military road. This study has raised the profile of the Palmerston forts and has led English Heritage to call for more detailed studies of the contribution that the forts make to the heritage of northern Plymouth and to the city as whole, and to their consideration within local area action plans.

Plymouth City Council intends to follow up on the renewed interest in the Palmerston Forts and their unifying heritage value, and intends to promote policies for their increased recognition within the emerging Local Development Framework"

It is my intention to further research exactly how this follow up is being undertaken. Practically nothing has filtered through yet to the various on-line resources bundled together under the heading of ‘Tourist Information’. A little patience will enable the determined browser to track down Plymouth City Council’s account of the Palmerston forts at: http://www.plymouth.gov.uk/palmerstonforts which does provide a basic account of the defences and also mentions the features which link them together such as the bank at St. Budeaux’s Churchyard but there is no map to show where the sites are located or suggestions for visits. An Email to Plymouth’s Tourist Information asking about details of the fortifications confirmed that they had nothing in print but they did make a helpful referral to the local studies department of Plymouth City Museum..

My personal feeling is that three very simple tasks could be undertaken at comparatively low cost which would at least make a start in raising public consciousness of these extraordinary monuments. Firstly a standardised information plaque should be attached to all sites – if vandalism is a problem print them in a large type face and fix them well above head height. Secondly a leaflet should be produced and circulated which offers the prospect of a guided walk or bike ride along some of these remarkable defensive lines. One could even imagine an event to publicise the launch of such a publication be recruiting some stalwarts from an organisation such as the Portsdown Artillery Volunteers to trundle a field gun along the line of defences pausing for photo opportunities en route! Finally the works which link the named forts and batteries should also be declared scheduled ancient monuments by English Heritage. Better knowledge of these sites may go a little way towards promoting greater understanding of their role in both the history of the city and the wider history of technology and perhaps help all those concerned with their welfare to take greater pride in their appearance and think more carefully about their long term preservation. One has top ask if this is a systemic problem given that in 1989 in Cherry and Pevsner's Buildings of England volume for Devon they write that : "... the deplorable neglect of worthwhile older buildings still continues, coupled with a lack of will to find appropriate new uses."

Principal Sources:

'Coast Defences of England and Wales' by Ian V. Hogg, David and Charles, Newton Abbot 1974

'The Historic Defences of Plymouth' by Andrew Pye and Freddy Woodward, 1996

On-line resources are linked to from the text.

A Note About Survey Methods.

It is remarkable the extent to which modern technology can help and support an enterprise such as this one. I have already mentioned the initial work that went on to prepare the ground before visiting. Using a combination of Bing Maps for access to Ordnance Survey maps and oblique aerial views and Google Earth for vertical aerial photographs with the facility to measure distances on the ground, contributions of photographs to Panoramio and of course Street View imaging it was possible to undertake a visit without leaving one's desk. Of particular value was Google Street View. Its detailed coverage meant I was able to track the course of banks and ditchs from street to street across the suburbs of Plymouth. As a tool this will obviously be of enormous significance to those studying fortifications in urban settings. All of this meant that when planning to visit sites on the ground a lot of time could be saved by heading to exact location of the relevant monuments.

Many people will be familiar with the techniques, some old and some new that can be deployed in producing a full measured survey of an archaeological or architectural site. At complex locations even with full access and co-operation from the authorities these can take days. Students of artillery fortifications know that in reality when access is granted it is often limited both in terms of duration and in the sense that some areas will be off limits. I was fully aware of the constraints of time and so did not undertake measured plan drawing, these were created from a combination of old maps and aerial views with some checking of details on the ground. However, I was aware that measured sectional drawings would be needed to illustrate fully the range of defences and that in some cases this work might have to be done, in the case of deep vertically sided ditches for example, remotely.

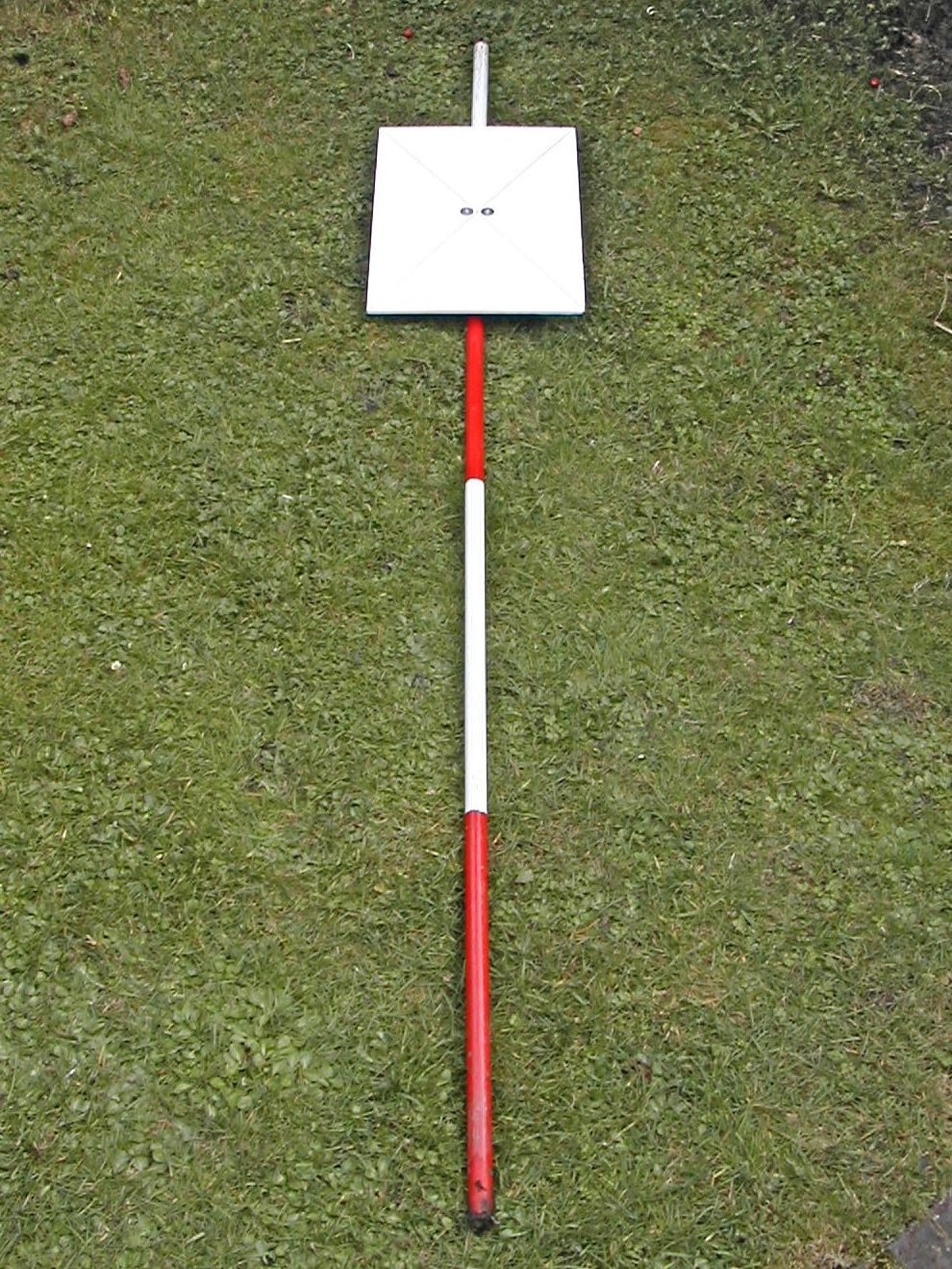

To this end I purchased for around 100 GBP a Bosch PLR50 Digital Laser Range Finder. With a claimed range of up to 50 metres this seemed an ideal entry level system. In addition I equipped myself with a couple of ranging rods and mounted a target onto one of them. In general terms over larger distances I was aiming for an accuracy of around plus or minus 1 percent, 10centimetres error either way over 10 metres. On the scale of monument we are considering that seemed about right given the uneven surface of some of the stonework or the overgrown nature of some of the earthworks. Where full access was possible using the target plate enabled a high degree of accuracy but where one had to operate from one side, at Grownhill for example it was only a moments work to take several measurements of the same distance and average out the differences.

The unit also has the facility to calculate heights, or indeed depths from a horizontal measure to the base of a structure (there is a built in spirit level, albeit tiny} and a sloping one to its top - or bottom. Of course this is not so useful on sloping surfaces but with the help of a number of measurements and a little trigonometry - actually to tell the truth I made scale drawings - it was possible to capture most profiles. Given the problems of establishing accurate measurements at many fortified sites i look forward to seeing how else the capabilities of this piece of equipment can be extended.

Stephen Wass April 2010