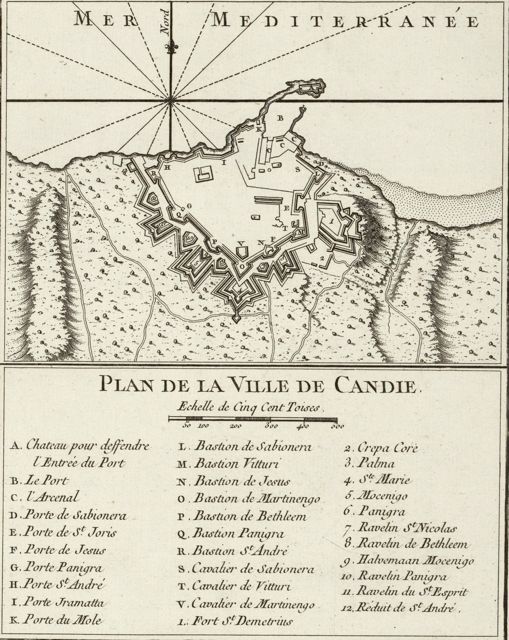

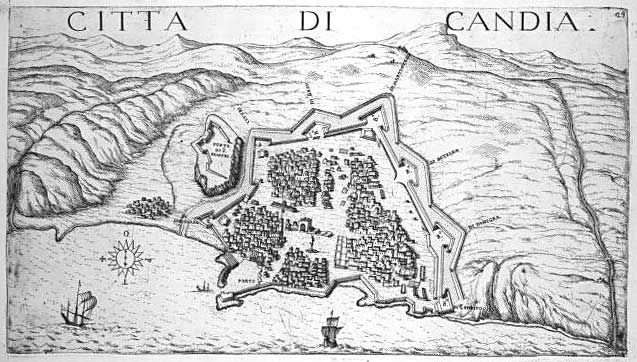

Heraklion

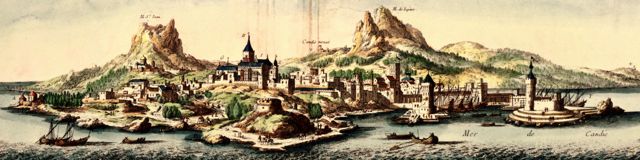

became one of the largest and most heavily defended cities in the

Mediterranean but its origins are uncertain. There are scattered

remains of Minoan settlement in the area and there may have been a

small town and harbour on the site in classical and early Byzantine

times. However, the town did not really take off until after the Arab

conquest of the island between 824 and 828 under the command of the

Saracen Abu Hafs Omar. Heraklion became the chief town of the island and

was used as a base for pirate raids across the Aegean. The town was

defended by a brick wall on stone foundations and further protected by

a wide ditch (Khandaq in Arabic) which lead to the town being renamed

Chandakas in Greek and Candia in Latin.

Crete

was retaken for the Byzantine Empire by the general, Nicephorus Phocas

in 961 and the devastated walls rebuilt. Chandakas became the largest

town on the island. The Fourth Crusade in 1204 and the fall of

Constantinople lead to Crete being ceded to the leader of the

Crusaders, Boniface of Montferrat, who sold the island on to Dandolo,

the Doge of Venice. The Venetians established control by 1211 and

developed the city to the point where it was viewed as second in

splendour and prosperity only to Venice itself. The growth of the town

lead to work beginning on a new set of walls in 1462 when the Venetian

senate, aware of the growing threat of the Ottoman Empire, ordered the

refortification of the city and its harbour. Local labour was

conscripted in on this huge project which occupied much of the

following century. In 1532 the Venetian engineer Michele Sanmicheli

arrived on Crete having previously worked on the fortifications

of Padua and Verona.

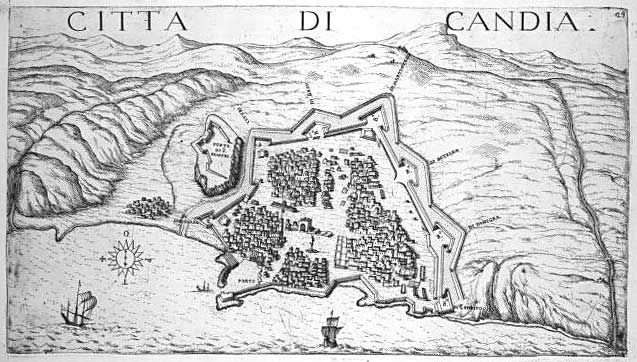

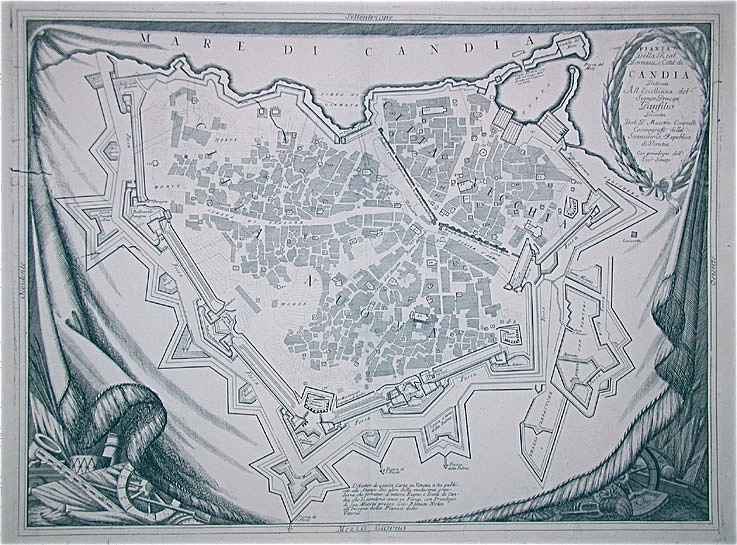

By the end of the 16th. century the town

was

defended by a huge circuit of walls with a perimeter of four and a half

kilometres. The massive nature of the construction meant that in places

the walls are 40 metres thick. The circuit boasted seven enormous

bastions with broad fronts and deeply recessed flanks and five city

gates. Additionally on a small hill immediately to the east

of

the town the detached Fort of St. Demetrius was erected consisting of a

trace with a small central bastion flanked by two demi-bastions. A

detached fort was built between 1523 and 1540 to protect the harbour. Known

as the Koules Fortress or the Rocca al Mare this rectangular

building has a large curved bastion overlooking the harbour entrance.

In a final phase of building the works were extended into the

countryside beyond the town with a series of detached ravelins, three

hornworks: two protecting the western wall and one in front of the

Jesus Bastion, and a crownwork to strengthen the Martinengo Bastion on

the south west corner of the town.

Boschini plan of 1651

In

1645 a Turkish fleet landed an invasion force in Western Crete which

progressively took over the entire island except for Heraklion which

was first invested in May of 1648. The siege continued for the next 21

years before being pressed to completion. In 1667 a Venetian

military engineer Colonel Andrea Barozzi defected to the Turks and

described to them the weak spots in the town’s defences especially

where they met the coast at St. Andrew’s Bastion on the west and the

Sabbionara Bastion to the east. A further blow came in 1669, when a

French expedition failed to lift the siege and lost

the

fleet's vice-flagship in an accidental explosion. Following these

setbacks the French abandoned Candia leaving General Francesco Morosini

with a much reduced garrison and limited supplies. He surrendered the

town on September 27th. 1669. The Turks repaired the town’s defences

but added few further improvements as the place became something of a

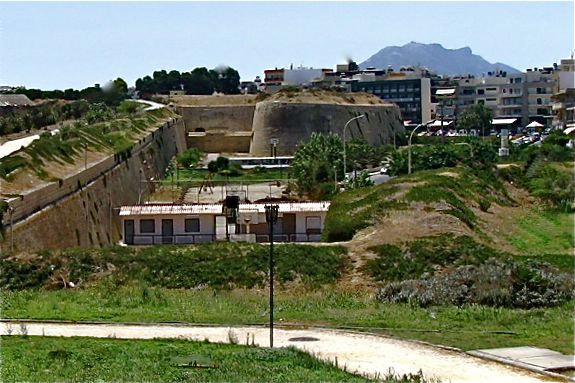

provincial backwater. The walls were seriously damaged by German

bombardments during the Second World War but have since, especially in

the last fifteen years, been heavily restored.

De Fer 1669 Plan showing Turkish Siege Works

Visiting Heraklion

Heraklion

today (2007) is a big bustling city with extensive modern development

beyond the line of the walls and a massive traffic problem within them.

Walking the entire circuit of the walls is perfectly possible

but

given their length can be quite grueling in the heat of summer. Work

continues to repair and restore the walls, especially along the west

side and as a result much of the area has a rather raw and

unfinished feel to it and can be particularly dry and dusty. Starting

at St. Andrew’s Bastion it is possible to follow a footpath along the

top of the wall to the Pantocrator Bastion.

Restored

section of St. Andrew's Bastion

Bethlehem Bastion from N

Crossing

over the top of the largely modern Bethlehem Gate the path continues on

to the Bethlehem Bastion rewarding the traveler with contrasting views

across the old town and the modern concrete suburbs. Much of the line

of the moat along here is taken up by public sports facilities. The

huge Martinengo Bastion contains a football pitch and in the well

preserved cavalier is the tomb of the Cretan writer Nikos Kazantzakis.

Beyond this point the area around the walls is quite heavily planted

which makes the environment much pleasanter but getting a good view of

the walls becomes increasingly difficult. Heading east takes us towards

the Jesus Bastion and beyond that the Vitouri Bastion with its very

overgrown cavalier. Leaving the line of the walls and threading our way

eastwards we eventually come to the restored St. George's Gate.

Curtain

and St. Andrew's Bastion looking N

Steps to

Martinengo Cavalier

Sabboniera Bastion from SW

View

towards St. George's Gate

SE curtain wall

Beyond

this, around 200 metres further east are the considerable remains of

the stone faced ramparts of the Fort of St. Demetrious which begins in

Archimidous Street. Back on the top of the wall we walk past the rear

of the Archaeological Museum towards the Sabboniera Bastion, now taken

up by a school and its playground. The walk can now be directed down

towards the harbour past the huge ruinous Venetian Arsenali or ship

sheds towards the Koules Fortress on the end of its breakwater. There

is an admission charge and opening hours, from Monday to Saturday 8.00

a.m. to 4.00 p.m. and 10.00 a.m. to 3.00 p.m. on Sunday. The interior

of the fort is well preserved and amply repays careful examination.

Koules

Fortress from SW

Venetiam

Arsenali from N

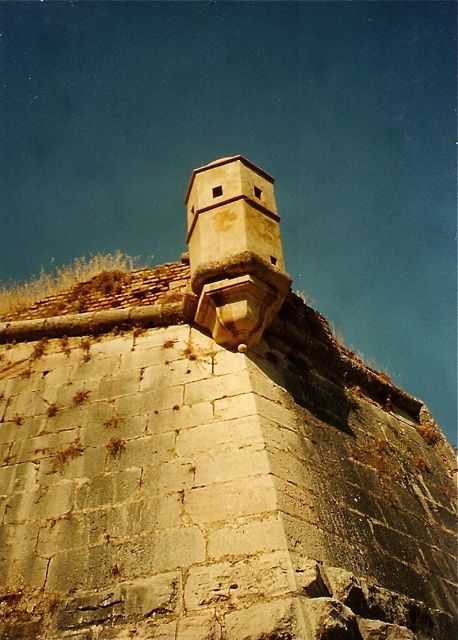

Koules Fortress

detail of NW corner

Finally

the story of the town and its defences is admirably told in the

Historical Museum at 27 Sofokli Venizelou Avenue, about 350 metres west

of the harbour on the coast road, open Monday to Saturday, from 9.00

a.m. to 5.00 p.m. closed on Sundays and holidays. It is a remarkably

pleasant alternative to endlessly congested Archaeological Museum!

Relief sculpture from the

facade of Santa Maria Zobenigo in Venice

Coronelli

1689

Bellini 1764

N Curtain, gate and NE

Bastion from N

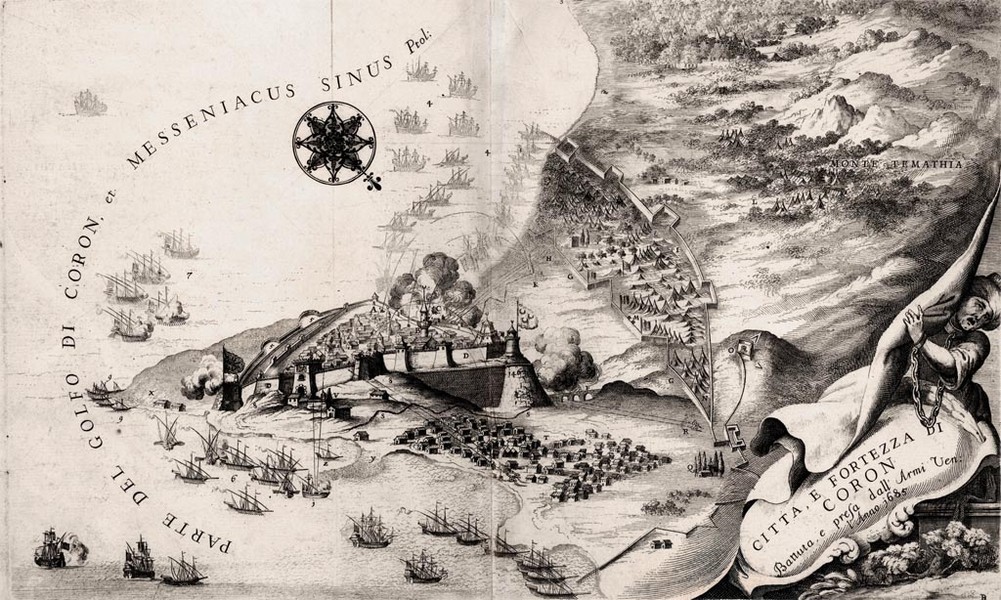

The

modern town of Koroni was founded in the 9th century on the site of the

ancient city of Assine. The remains of the classical temple to Apollo

can still be seen on the highest point of the headland, the

ruins intermingled

with an early Christian basilica and a small Byzantine

Church. In 1205 the town was captured by the Franks but they

in

their turn were expelled by the Venetians in 1207 who set about

strengthening the walls. The town together with Methoni became a vital

link in the chain of defended harbours which sustained Venetian trading

and commerce.

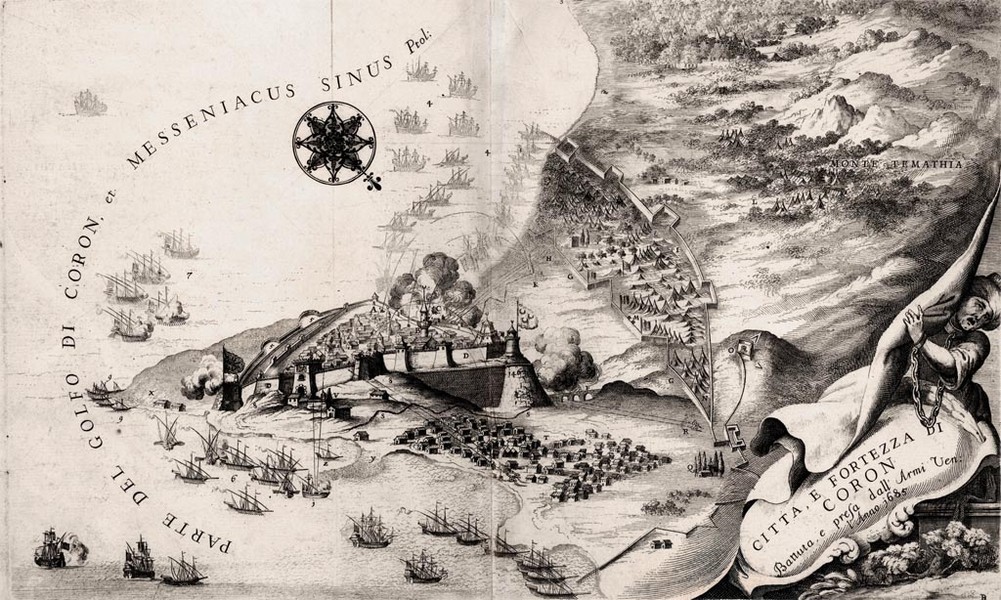

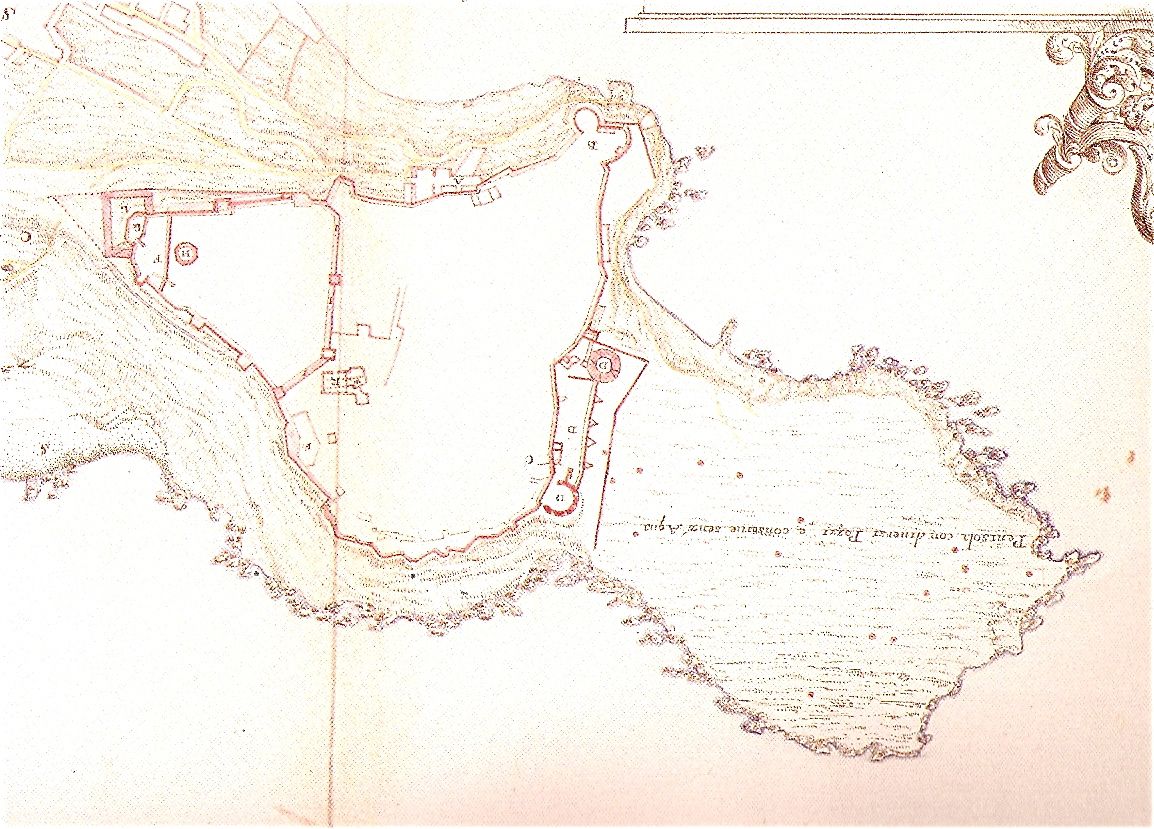

Drawing

by De Witt 1680

Siege of 1685

Venetian plan from Grimani

Portfolio 1700

Following

the capture of Methoni in 1500 and the subsequent massacre of its

defenders the local population were unwilling to mount a defence and

abandoned the town. In 1532 the Genoese admiral Andrea Doria assaulted

the town at the behest of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V but was only

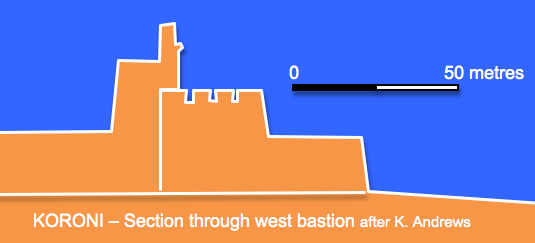

able to hold it for 2 years before it was retaken by Turkish forces. Both maps indicate a double line The fortress

fell after a two parallel galleries packed with 250 barrels of

gunpowder had been used to blow up the massive western bastion. The

fortress returned to Turkish control when Venetian forces pulled out in

1715. Following the Greek uprising of 1821 the Greeks attacked the town

but were unsuccessful in taking it. The fort was eventually surrendered

together with Pylos and Methoni to the French general Maison in 1828.

Interior

of N gate

N gate

and curtain looking W

Square tower on S

curtain

W

Bastion from NE

Repairs to E curtain

Terrace and SE bastion from N

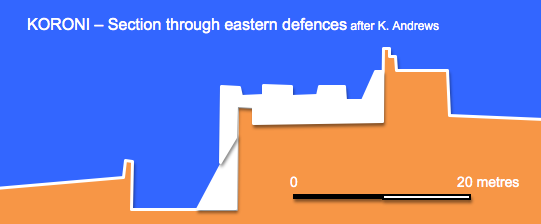

It

is possible to reach the southern curtain beyond the adjacent

churchyard to enjoy striking views of the square towers set above a

massive sloping talus to the west before turning to the east and

following the wall along the cliff top towards the eastern defences.

These consist of four massive circular artillery towers in a north

south line cutting across the headland. The southern most two are

linked by a double wall and terrace with an outer moat. Considerable

restoration work is underway here (2008), the central bastion was badly

damaged by an explosion during World War II. The southernmost tower

encloses a single huge chamber with the roof being supported by a

central octagonal pillar 11 metres high. The chamber contains four

casements at floor level covering the approach to the harbour whilst

there are five further emplacements on the roof. At the north east

corner are two linked circular bastions at different levels containing

embrasures and musket loops.

Bibliography:

Castles of the Morea by Kevin

Andrews, Revised Edition, Princetown 2006

Venetians and Kinghts

Hospitallers – Military Architecture Networks, by Archi-med

Pilot Action, Athens 2002

Pylos – Pyla – A Journey

Through Space and Time by G. and T. Papthanassopoulos, Athens 2002

Fortresses and Castles of

Greece, Volume 2 by A. Paradissis, Athens 1994

Crusader castles in Cyprus,

Greece and the Aegean 1191 – 1571 by David Nicolle, Osprey Publishing,

London 2007

Venetian

Fortresses in Greece at: http://romeartlover.tripod.com/Venezia.html

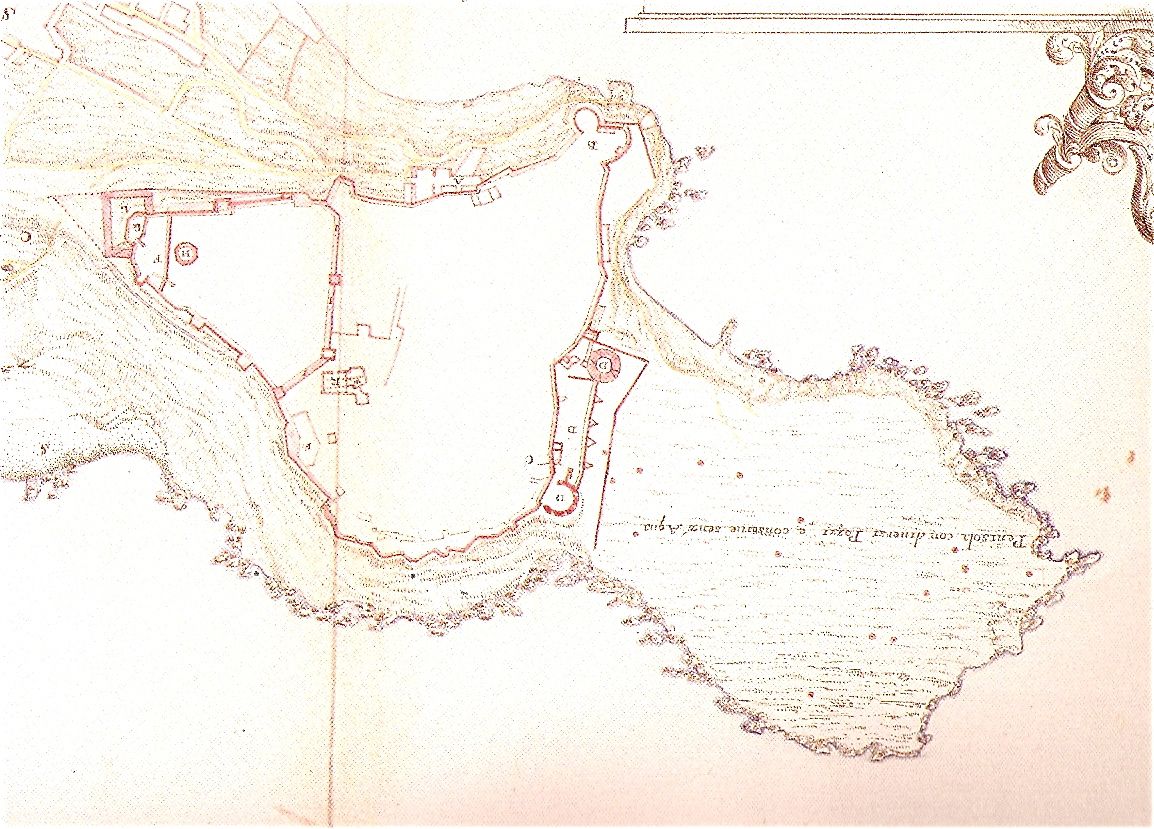

Methone

This

small flat peninsula with its natural harbour to the East has been

occupied and fortified from the earliest times. It featured in the

Peloponnesian wars of the 4th century BCE, was taken by the Macedonians

and Romans and was later an important port and fortress for the

Byzantines. Following the collapse of the Byzantine empire after the

fourth crusade the town was taken by the Franks in 1205 then occupied

by the Venetians the following year. They maintained it as a trading

port until 1500 when it fell to the Turks. The Knights Hospitallers

failed to recapture it in 1531 and it remained in Ottoman hands until a

three week siege in 1686 began the second period of Venetian

occupation, By 1715 the Turks were back in control and remained so

until the Greek War of Independence following which in 1828 it was

briefly base to a French contingent. Italian forces built pillboxes

around the site, now largely removed, and it was damaged by two

separate explosions during WW II.

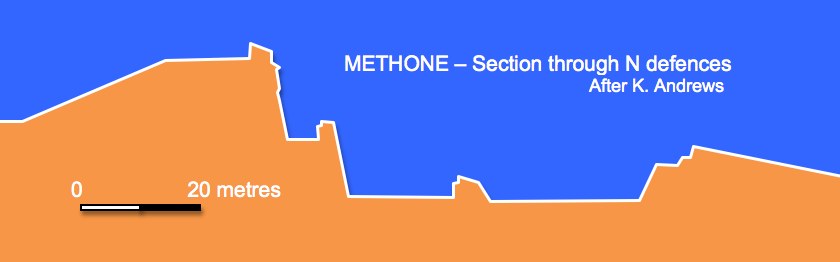

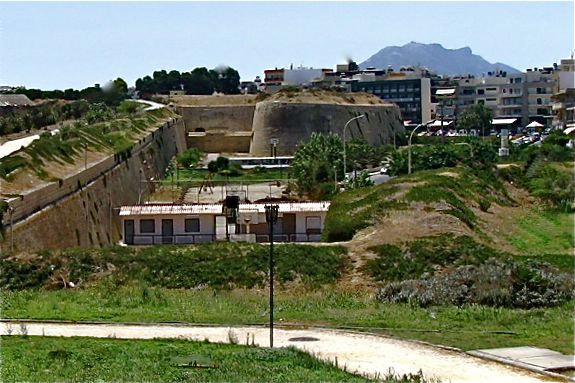

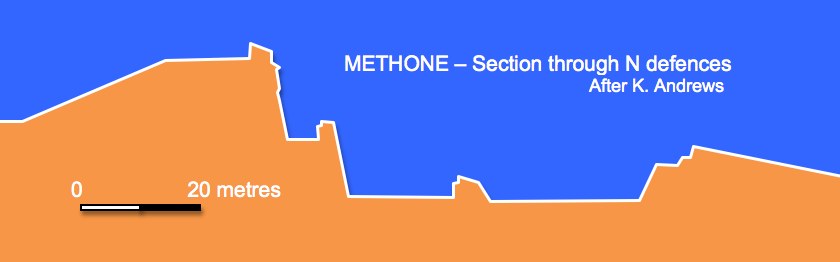

The

land front on the Northern side of the old town is the most strongly

defended sector. A broad ditch separates the peninsula from the

mainland. This was designed to be flooded by the sea but after several

remodellings remained unfinished. To prevent access to the north end of

the ditch a detached battery was built in the early 18th century . A

fausse braye defends the ditch between flanks of two bastions: Loredan

to the East and Bembo to the west.

The

Bembo Bastion from SE

Bridge and main gate from N

The

two bastions are linked by a double curtain wall which creates a

covered way between them. The inner wall may contain elements of the

original Byzantine defences although it is mainly from the first period

of Venetian occupation. In the 15th century it was strengthened with a

central round tower and the wall was reinforced by a hefty earth

rampart and a curved bulwark built at the east end. Late in the century

the fan shaped Bembo Bastion was added at the west end. Early 18th.

century improvements saw the Loredan Bastion built in front of the

eastern bulwark and the covered way extended to the east of the Bembo

Bastion to create a demi-bastion at a lower level. An additional

flanking battery in the shape of a demi-bastion was added to the

south.

The

entrance to the site is across a stone bridge built by the French in

the 19th. century to replace the earlier wooden one. The present outer

gateway is a fine example of early 18th. century Venetian work and is

decorated with carved flags and pikes. At the eastern end of the

covered way is a late medieval double gate giving access to the main

part of the town although the northern section immediately behind the

land front is closed off by a wall with square towers and a single gate

all dating from the 16th. century Turkish occupation.

Inner

Fortress Wall looking NW

The Sea Gate from S

The

wall around the remainder of the town follows the coast line and is

mainly 13th. century with considerable patching and other additions from

the following centuries. East of the Sea Gate is a square tower of the

16th. century ruined by a World War II explosion!

At

the southern tip of the peninsula is the Sea Gate with two square

towers, the eastern tower has some earlier Venetian material but the

entrance was remodelled in the 16th century with addition of the

western tower. A causeway links the gate to the small island fortress,

the Bourdzi. This octagonal lantern shaped tower of the 16th. century

has two levels within an outer wall with a loop holed parapet. Another

World War II explosion took out a section of the western curtain wall

revealing

the huge depth of stratified archaeological deposits which has built up

on the site.

Other

surviving buildings include two 18th. century powder magazines, one with

pyramidical roof, a ruined Turkish Bath and a 19th. century chapel. Some

clearance has been done opening out the lines of streets and lanes from

the town which was finally abandoned early in the 19th. century

Magazine

from S

Stratification N

side of peninsula

looking S

Visiting

Methone

Public

transport options for getting to Methone are limited. There is a bus

service from Kalamata but for those who drive there is a free car park

on the site of the former glacis. The ticket office is sited on the

landward side of the bridge but when not staffed the gates appear to be

left open. Since the 1970s there have been sporadic campaigns by the

Greek Ministry of Culture to consolidate and restore the remains

despite this the area remains fairly unkempt and the walls in places in

poor condition. There is plenty of accommodation and several good

tavernas in town including the Methoni Beach Hotel (good for a cold

beer and fresh orange juice) and the Akro Giali restaurant which

lie on the beach next to the Loredan Bastion. There was no

guidebook to be had on site but the widely available publication “Pylos

– Pyla – A Journey Through Space and Time” has very good coverage of

all the fortifications in the vicinity.

Bibliography:

Castles of the Morea by Kevin

Andrews, Revised Edition, Princetown 2006

Venetians and Kinghts

Hospitallers – Military Architecture Networks, by Archi-med

Pilot Action, Athens 2002

Pylos – Pyla – A Journey

Through Space and Time by G. and T. Papthanassopoulos, Athens 2002

Fortresses and Castles of

Greece, Volume 2 by A. Paradissis, Athens 1994

Crusader castles in Cyprus,

Greece and the Aegean 1191 – 1571 by David Nicolle, Osprey Publishing,

London 2007

Venetian

Fortresses in Greece at: http://romeartlover.tripod.com/Venezia.html

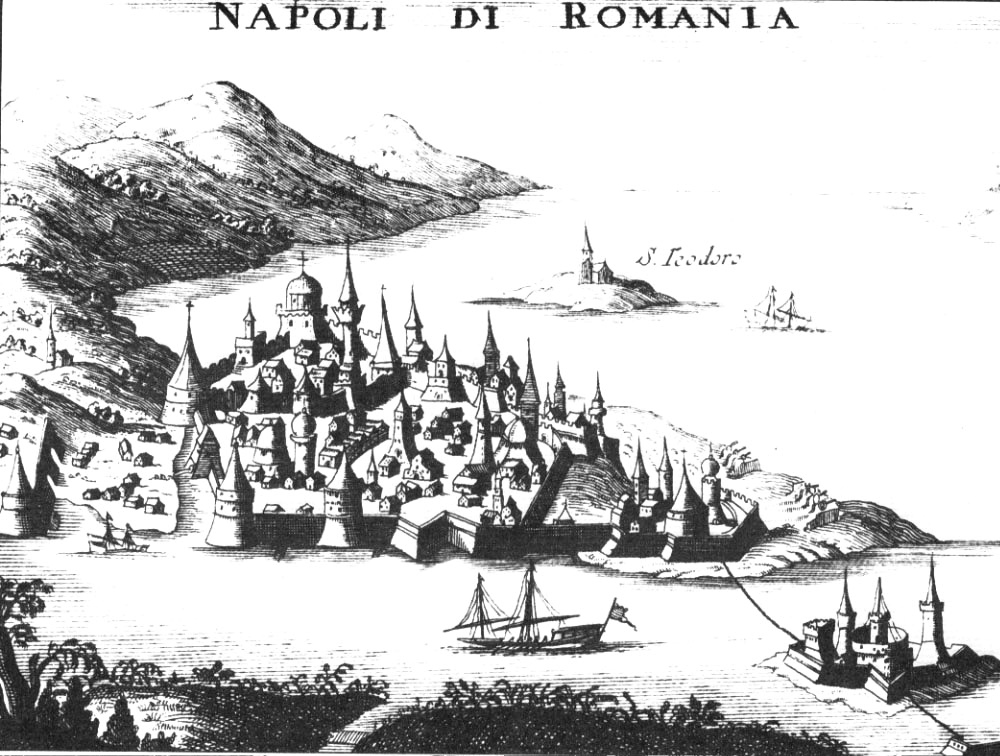

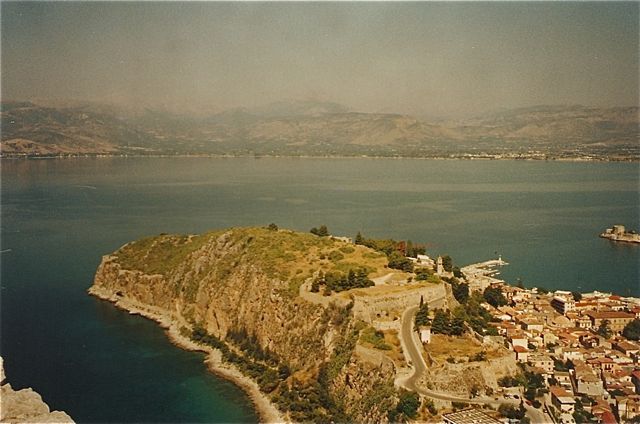

Nauplion – Palamidi

The

complex of fortifications centred round the town of Nauplion (or

Nafplion) is one of the most important and spectacular on the

Greek mainland. Defensive works from many eras are easily accessible

with the shady streets of the town offering respite and refreshment

between periods of ruin hopping.

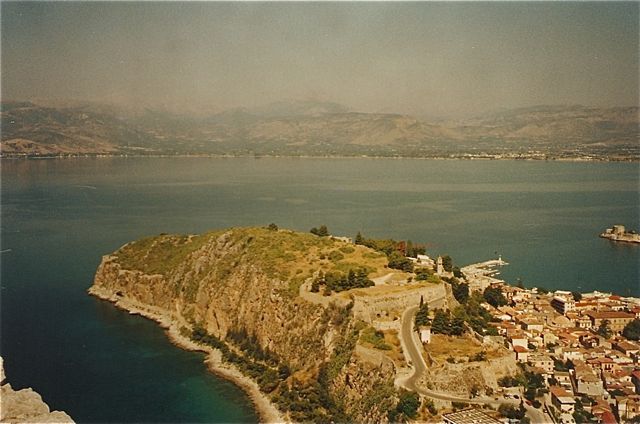

The

modern town stands on largely reclaimed ground below a rocky promontory

that juts out into the Argolic Gulf. According to myth the town’s

founder was Nauplios, son of Poseidon. His son, Palamedes, after whom

the crag that dominates the town was named, was a participant

in

the Trojan War and was credited with the invention of writing. Whatever

the town’s early origins it was clearly an important port from the

outset and there are traces of a Mycenaean defensive wall near the S

corner of the Castello di Toro. The developing town was destroyed in

600 BCE by Argos because of its links with Sparta but by the

Hellenistic period it was sufficiently recovered to boast a fortified

acropolis. At a number of locations the roughly coursed rubble walls of

the medieval period are underpinned by the massive dressed ashlar

blocks from the classical walls.

Arab

incursions in the late 6th. century may have prompted a refortification

of Acronauplia by the Byzantines. Further work was probably undertaken

in the 11th. century, especially after Nicephoros Karentinos was

appointed ‘general’ of the town following a decisive defeat for Arab

forces in 1032. It is likely that a wall was extended to cover the

growing town at the foot of the acropolis in the 12th. century. After

the fall of Constantinople in 1204 and a successful two year siege by

the Frank, Godfrey de Villehardouin in 1210 the works of Acronauplia

were divided into two sections, the western most being left in the hands

of the Greeks – Castello di Greci, while the invaders occupied the

eastern portion – Castello di Franchi. In 1382 following difficulties

over inheritance the rights to the town were ceded to the Venetians who

took control for the next century and a half.

The

Venetians improved the layout of the town, erected a number of public

buildings and strengthened and updated the defences of both Acronauplia

and the town. They repaired the walls of the two earlier castles and

added the Castello di Toro to cover the approach from the

east.

They also erected in 1471 the small defensive work on an islet in the

harbour known as the Bourdzi. By 1530 the population stood at around

10,000. However, after fending off a number of Turkish raids the town

finally fell to Kasim-Pasha, vizier to Sultan Suleiman I, in 1540 after

a three year siege. The town was forced to capitulate having been

largely reduced to rubble by cannon mounted on the nearby Palamidi Hill

that overlooks the town.

1573

1686

17th. century

Following

the fall of Crete to the Ottomans the Venetian general

Francesco

Morosini attacked the town in 1686. The destruction of a powder

magazine close to the Land Gate together with much of the south east

quarter of town lead to the surrender of the Turkish forces. It had

become clear that the existing fortifications fell far short of what

was required for modern warfare. As well as reinforcing the entry to

the Acronauplia and covering the Land Gate with the massive Grimani

Bastion and strengthening the remaining walls and towers they also

began work to turn the towering crag of Palamidi into an utterly modern

and impregnable fortress. Its design was the responsibility of two

engineers: a Frenchman, La Salle and a Dalmatian, Giaxich, and it was

largely completed between 1711 and 1714, a remarkably short period for

such a massive undertaking. However, in 1714 when the Ottoman general

Ali Dagut Pasha attacked with an army of over 100,000 there were only

1,700 defenders to oppose him and the Palamidi fell after a siege of

just two weeks allegedly because of the treachery of its French

commander.

1700

During

the second period of Turkish occupation the town became something of a

provincial backwater and little was done with its defences except an

extension eastward to the Palamidid and some limited maintenance work.

At the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in 1821 a series of

attacks and a protracted siege lead to the fall of the town and its

defensive works in November 1822. From 1828 to 1834 Nauplion

was

the first capital of the new Greek state.

Visiting Nauplion – Palamidi

Acronauplia

The

headland can be approached on foot from the town. Any one of a number

of lanes approach the foot of the acropolis rock at which point one

turns left and follows a path that leads through a gate flanked by a

round tower into a open space in front of the east facing wall of the

Castello di Franchi. Try and ignore the decaying concrete and glass

former Xenia Hotel that takes up most of the internal space of the

Castello di Toro.

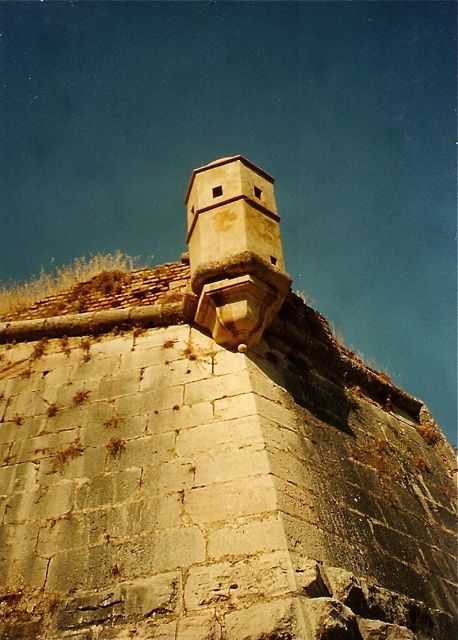

Gate

to Castello Di Toro from W

N wall of Acronauplio looking E

E Wall of

Castello Di Greci

A

road curls

round the southern end of

this wall

revealing the ruins of a number of chambers built against the inside

face. Further up the slope is the massive cross wall which marks the

eastern limit of the Castello di Greci, reinforced by the Venetians

with a talus and a low round tower loopholed for musket fire. The hill

top beyond this is an overgrown and rather confusing jumble of low

ruined walls and impenetrable scrub. Retracing one’s steps and

following the road past the derelict hotel leads to a large circular

artillery tower of the late 14th. century which marked the eastern end

of the Castello di Toro. Beyond this is the huge quadrangular Grimani

Bastion of 1706. This replaced an earlier detached ravelin and was

contiguous with the east front of the town wall. The bastion was banked

inside into three terraces backing onto the parapet with embrasures.

Below these are a series of vaulted galleries. Part of the walling

consists of large rusticated blocks of stone which are carried up the

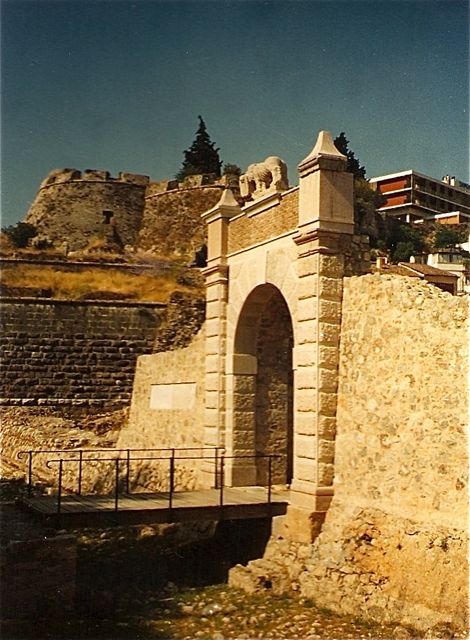

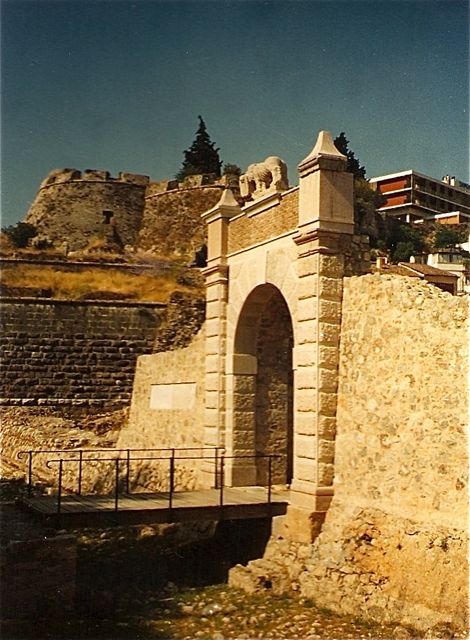

angle of the bastion to the height of the cordon. In a park below the

bastion are the reconstructed remains of the Land Gate and a section of

town wall and moat.

Grimani

Bastion

Acronauplio from E

Restored Land Gate with Grimani Bastion and 14C artillery tower

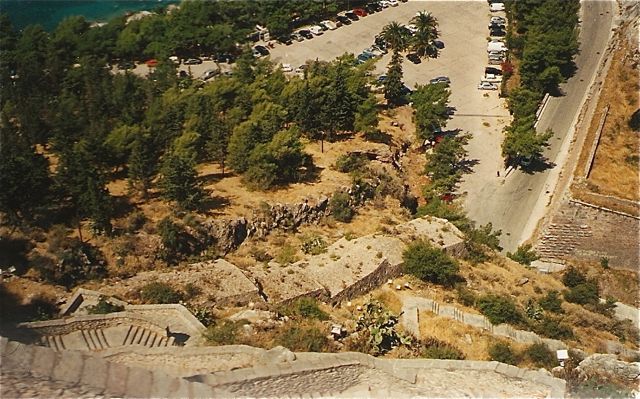

Steps on W face of Palamidi

and Caponier

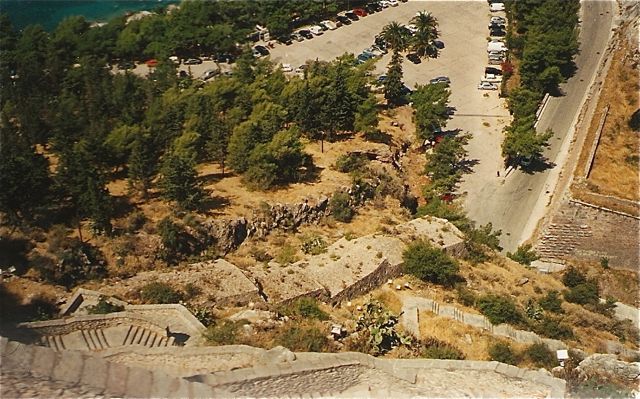

Vehicle

access is available from the town but many visitors prefer to

experience the extraordinary climb up the staircase which zig-zags up

the northern face of the crag. This can be quite challenging as for

much of the day the 900 or so steps rising around 200 metres are in

full sun. However the ascent does offer a magnificent unfolding

panorama of the old town and Acronaupila and a view of the curious

loopholed caponier like structure which runs down the lower portion of

the slope. Half way up one passes the small Robert Bastion

before

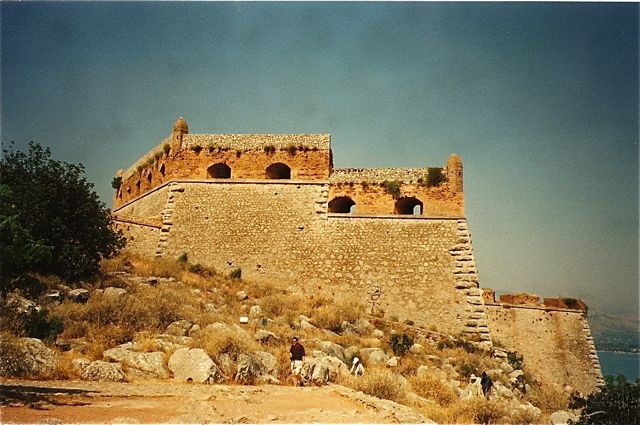

entering through a series of gates and terraces the massive Ag. Andreas

Bastion. This was the first to be completed in 1712 and illustrates

well the concept behind the fortress which is that of a series of

detached and semi-independent forts located within a larger but less

heavily defended outer enclosure wall. The bastion was fitted

out

as the command point for the garrison and as well as residential

accommodation included a small church dedicated to St. Andrew. The

walls can be approached either by steps or a horribly slippy steep

stone ramp now highly polished by the feet of passing tour groups.

The

Robert Bastion

The

Ay. Andreas Bastion from

E

The

Ay. Andreas Bastion Interior

To

the north is the small Leonidas Bastion defending the northern most

corner of the enciente and beyond this looms the huge bulk of the

Miltiades Bastion, really a detached pentagonal fort in the form of an

acute angled ravelin pointing towards the main land approach from the

east. It contains a large rainwater cistern and a number of dismal

chambers which functioned as prison cells from 1840 until 1920. Further

east against the cliff top is the Themistocles Bastion

containing

a six gun battery which would also flank the approach road from the

east and dominate a ridge which extended along the cliff top further to

the east. The Achilles Bastion occupies the central portion of this

ridge but was possibly unfinished at the time of the Turkish assault as

it was here that the breakthrough was made. Beyond it is the Phokion

Bastion built by the Turks after 1714 to strengthen what they obviously

saw as a weakness in the defences.

The

Miltiades Bastion from W

The Themistocles Bastion from N

An

admission charge is made and the whole site is freely accessible

although there is little by way of facilities within the

fortress

except for a couple of water taps.

The Bourdzi

The

Bourdzi.

This

well preserved little fort has fulfilled a number of non-defensive

functions including being the home for the town’s executioner. More

recently it has been a hotel, a restaurant and a cultural centre. There

are many small boats available with boatmen to take visitors round the

island but it is best to check with the tourist information office

opposite the bus station for current arrangements for access.

Bibliography:

Castles of the Morea by Kevin

Andrews, Revised Edition, Princetown 2006

Venetians and Kinghts

Hospitallers – Military Architecture Networks, by Archi-med

Pilot Action, Athens 2002

Fortresses and Castles of

Greece, Volume 2 by A. Paradissis, Athens 1994

Nauplion-Palamidi by E.

Spathari, Hesperus Editions, Athens 2000

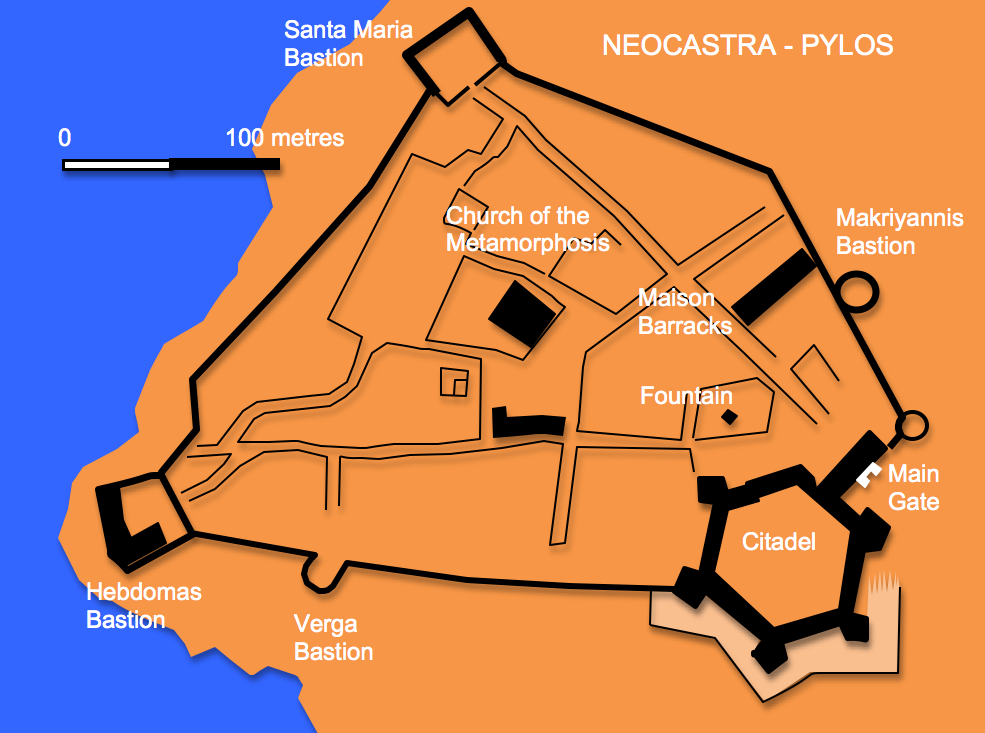

Pylos – Neocastro

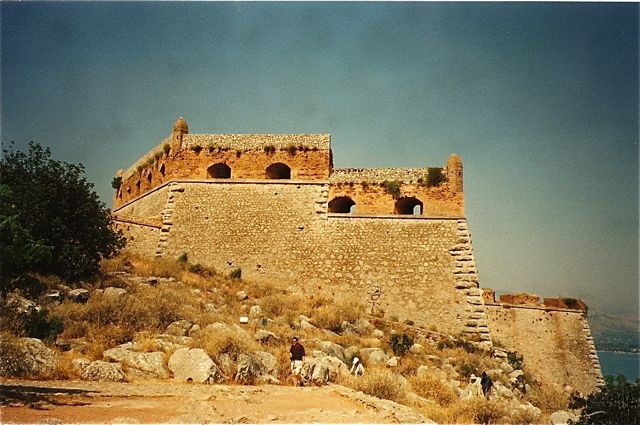

The

Bay of Navarino on the west coast of the Peloponnese has a long

military history stretching back to the construction around 1300 BCE of

the Mycenaean citadel known today as ‘Nestor’s Palace’ some 8

kilometres to the north. In 425BCE at the battle of

Sphakteria

the Athenians defeated the Spartans below the classical city

of

Koryphasion which in its turn became a Byzantine

citadel

and a castle constructed after 1278 by the Franks and strengthened by

the Venetians and Turks, now known as the Paleocastro.

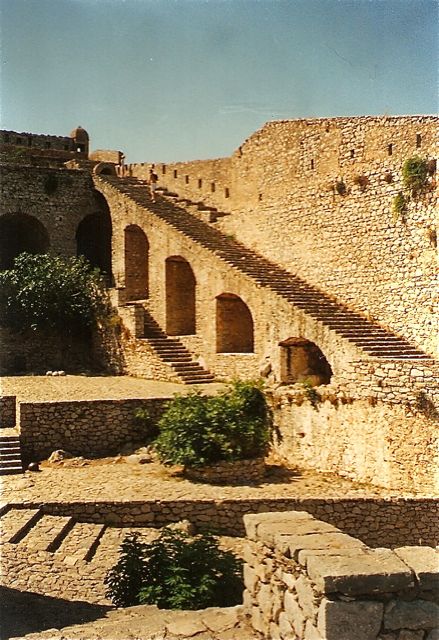

N gate, paved way and Maison

Barracks

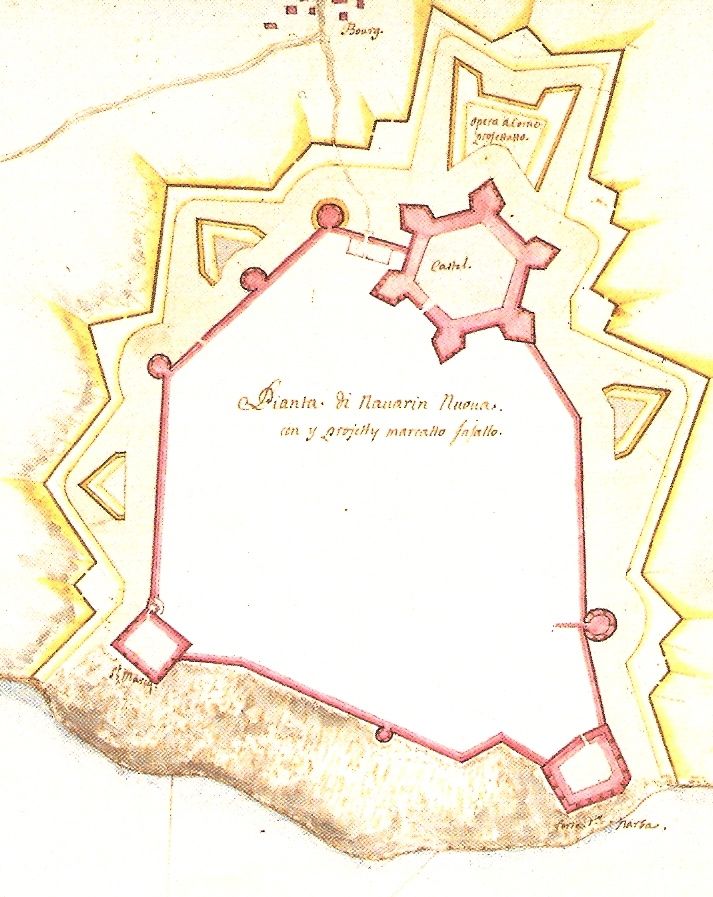

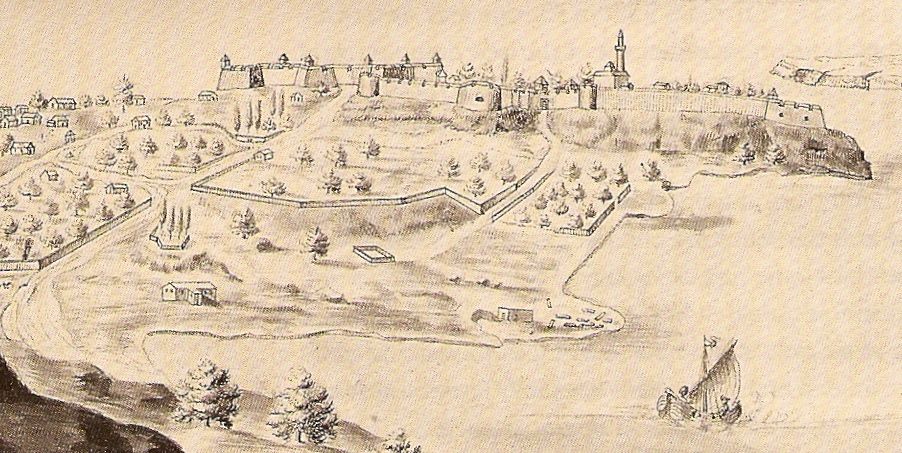

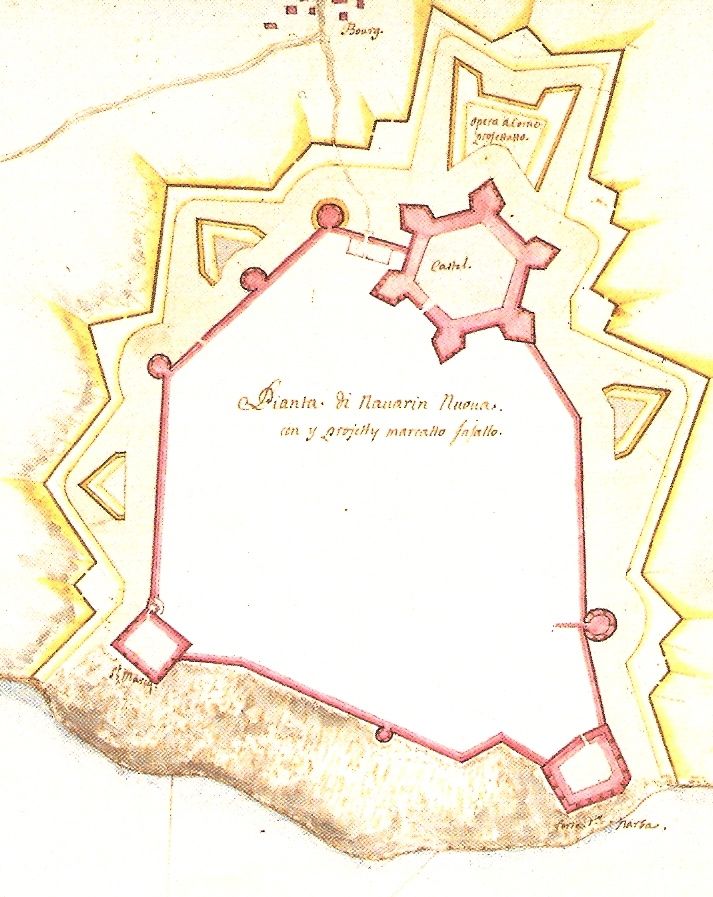

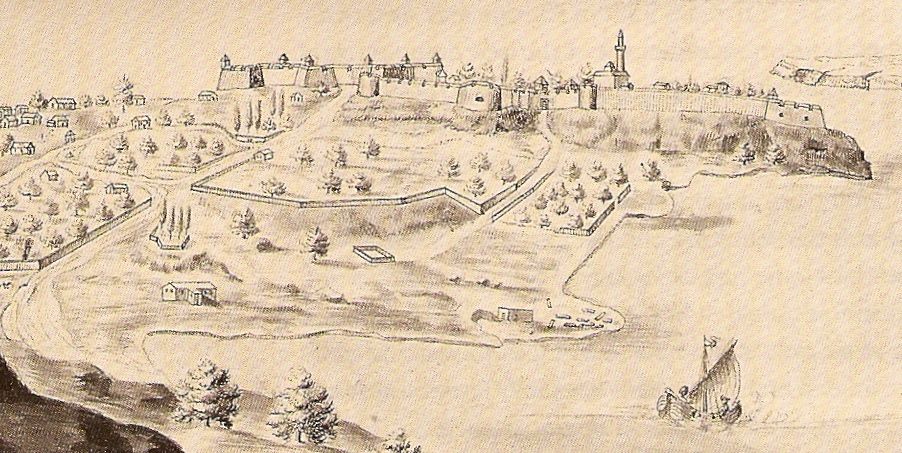

In

1573, two years after the naval battle of Lepanto the Turks further

strengthened the defences of this important anchorage with a new work

opposite the southern entrance to the bay.

This

consisted of two large rectangular batteries dominating the entrance to

the harbour which may be earlier than the hexagonal bastioned citadel

on the crest of the hill. Between these was laid out a small walled

town with a central mosque. In 1686 the fortification was taken by the

Venetians under Francesco Morosini after a 12 day siege. During the

course of this operation and powder magazine exploded destroying the

northern most bastion of the citadel. The Venetians were quite

dismissive of the site’s military value citing its poor position and

lack of ditch. Ambitious proposals were drawn up for work including

three detached ravelins and a hornwork defending the approach to the

citadel from the east but apart from the construction of two curious

little loopholed ravelins in the ditch around the citadel little was

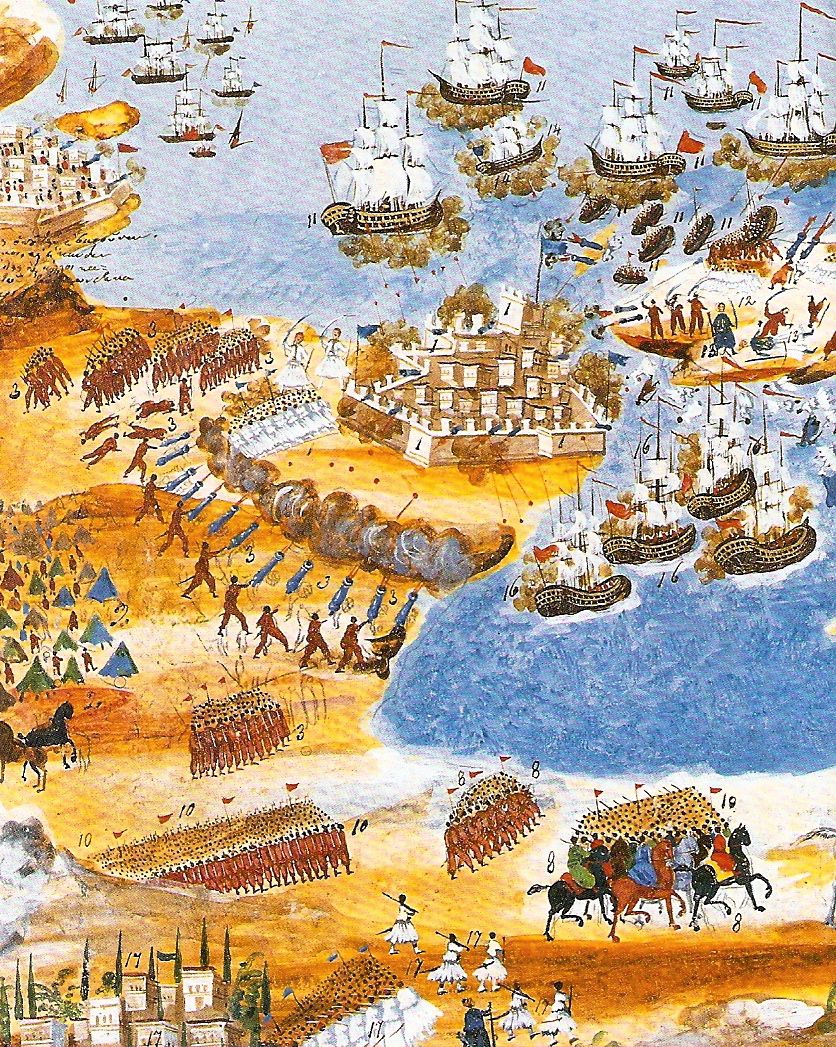

done. In 1715 after a lightening campaign by the grand vizier Ali

Kioumourtzi Turkish rule was restored and the Venetian forces driven

out. The declaration of war on the Ottoman Empire in 1770 by Russia saw

an attack on defences in the area by a small Russian force under the

brothers Orloff working together with local Greek forces. Neocastro

surrendered after a six day bombardment, however, following the arrival

of an Ottoman army consisting of several thousand Albanians the

Russians in turn withdrew. This failed uprising had tragic consequences

some of which were replayed in the Greek war of Independence

(1821 -1828). The Greeks captured the fortress after a siege lasting

several months and then held it until in 1825 Ottoman forces under

Ibrahim Pasha from Egypt landed and retook it. Intervention by the

three European powers of Britain, France and Russia saw the arrival in

1827 of a large combined fleet who anchored in the bay. Here they

clashed with a Turkish fleet whose almost total destruction signaled

the collapse of Turkish domination of the area. The castle was

surrendered to the French general Maison who carried out some repair

work and erected a new set of two storey barracks.

Venetian

Plan

and view early 18th century

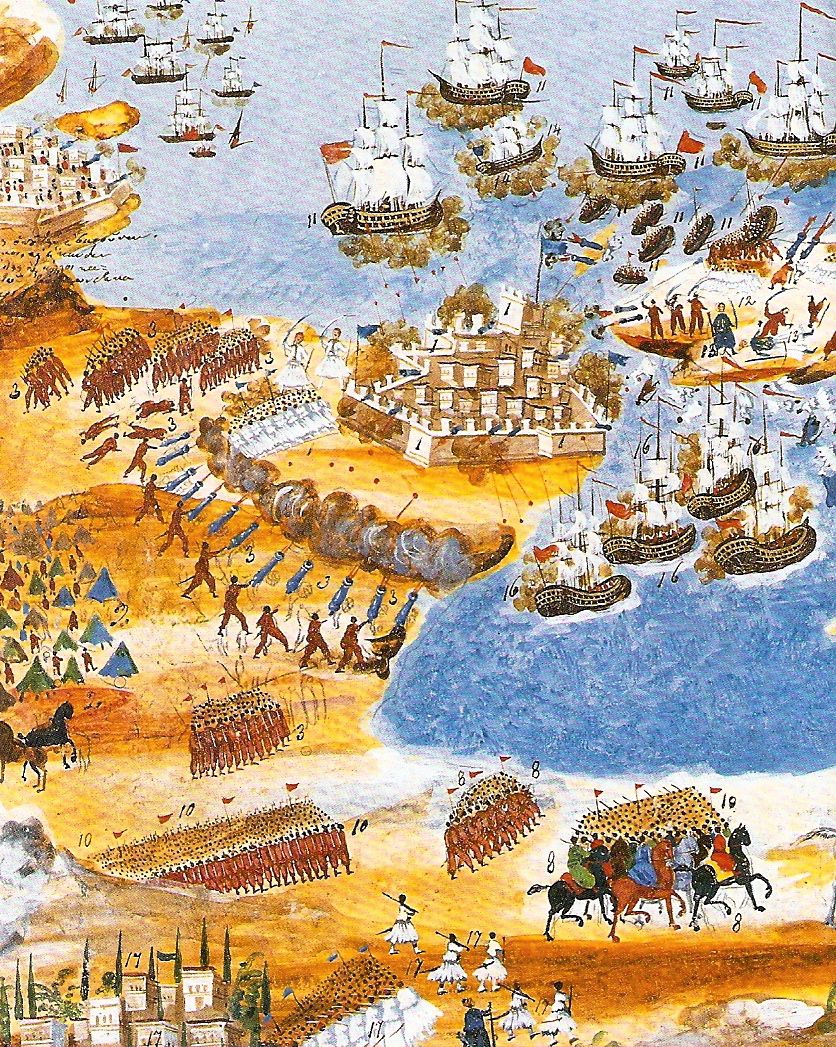

Painting of 1825

seige

The

castle became a prison in 1864 and the interior of the citadel was

partitioned with radial wars to control the prisoners. During the

Second World war and number of gun emplacements were set up around the

castle. A major programme of restoration and rebuilding was carried out

between 1982 and 1987 opening part of the barracks as an art gallery

and setting aside other areas to serve the needs of the Greek

Centre for Underwater Archaeology.

Visiting Pylos – Neocastro

The

pleasant little town of Pylos can be accessed either bus from Kalamata

but for the independent traveler the best solution is to fly into

Athens and hire a car. This then also allows visits to be

made to

Koroni, Methoni and other sites in the area. The castle is open to the

public from Tuesdays to Sunday 8.30 a.m. to 3.00 p.m. with an entrance

charge of 2.50 Euros (2008).

Santa Maria

Bastion from N and S

Makriyannis Bastion from NW

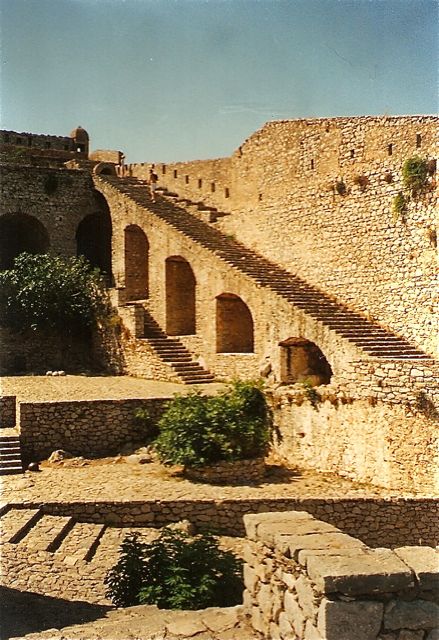

Public

entrance is through a simple gate in the curtain north of the

Makriyannis Bastion. To the left is the restored Maison barracks and

the path leads to a crossroads in the centre of what would have been

the old town. To the right a path leads up the hill to the citadel past

a small rectangular fountain house. This was formerly fed by two

aqueducts which brought water to the town. The original main gate lay

to the north east of the citadel and consists of a heavily buttressed

square tower. The hexagonal citadel is now flanked by five (one having

been destroyed) small two story bastions. The citadel is entered

through a simple gate on its north face and a broad ramp gives access

to the wide paved wall walk which links all the bastions and the gate

tower.

The Citadel: Entrance from N,

Ramp looking E, S Bastion from NE

The

southern curtain carries an arcaded wall walk down to the semi-circular

Verga Bastion the interior of which was destroyed by British bombers in

1943 while the fortress was occupied by the Italians.

Overlooking

the rocky coast at the south west corner is the Hebdomas Bastion also

known by the Venetians as the Forte Santa Barbra. This carried 15

cannon placed at two levels. It was largely destroyed during the attack

of 1825 and rebuilt by the French. At the northern corner of the site

stands the second rectangular bastion known as the Santa Maria. The

interior contains a variety of overgrown foundations and ruins as well

as the aptly named Church of the Metamorphosis having been converted

either from mosque to church or vice versa no less than seven times.

Sadly it is currently closed having been badly damaged by fire.

The

Hebdomas Bastion, interior looking S

Church

of the Metamorphosis

from E

Aqueduct E of citadel

Bibliography:

Castles of the Morea by Kevin

Andrews, Revised Edition, Princetown 2006

Venetians and Kinghts

Hospitallers – Military Architecture Networks, by Archi-med

Pilot Action, Athens 2002

Pylos – Pyla – A Journey

Through Space and Time by G. and T. Papthanassopoulos, Athens 2002

Fortresses and Castles of

Greece, Volume 2 by A. Paradissis, Athens 1994

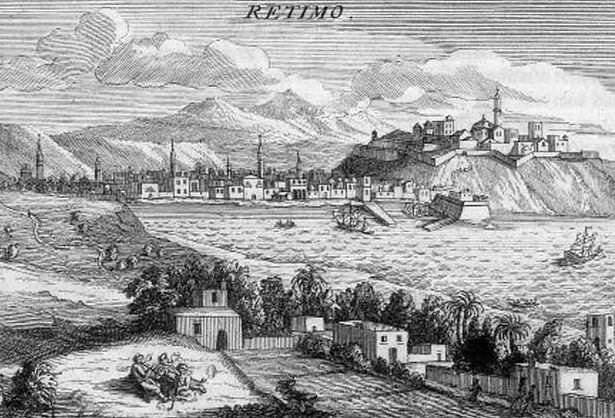

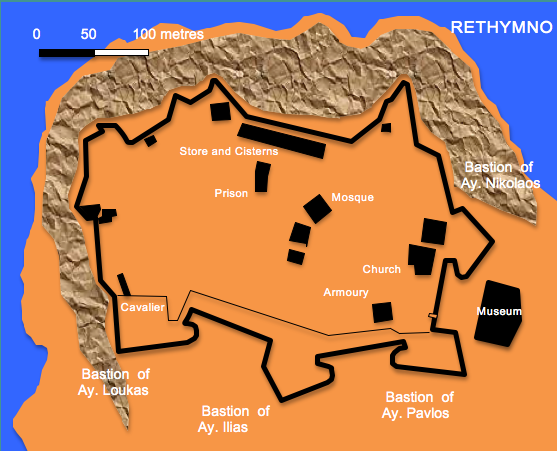

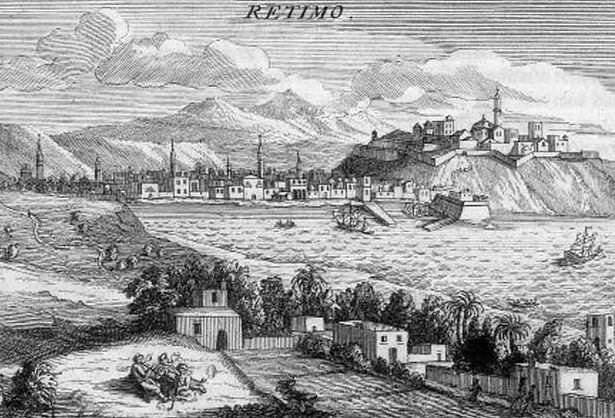

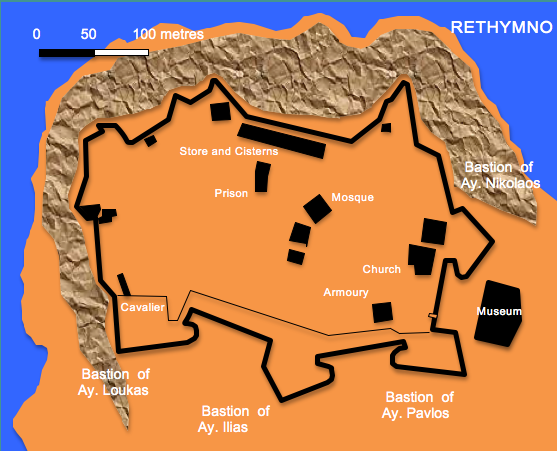

The Fortetza of

Rethymno - Crete

The

rocky coastal headland at Rethymno in northern Crete has been occupied

since prehistory. In classical times it is likely that the area was

site of an acropolis and temple to Artemis whilst the civil settlement

occupied the ground covered by the modern town. Little is known of the

town during the early Byzantine (325 – 824) and Arabic (824

-961)

periods. During the second Byzantine period (961 – 1204) a defensive

wall with round towers enclosing a roughly triangular area was built

next to the small harbour. This was taken over by the Venetians,

following the fall of Constantinople to Frankish and Venetian forces in

1204 but it was not until the disaster of 1571 when a Turkish raid

resulted in the destruction of a newly constructed city wall and the

Byzantine Fortress that thoughts turned to refortifying what was known

to the Venetians as the palaeo kastro or ‘old castle’.

Approach

from S, ravelin on right

Main Gate from NE

In

1573 work began on this new larger fortification on the site of the old

acropolis which would, it was hoped, be large enough to rehouse the

whole population. Initial plans were drawn up by the architect Sforza

Pallavicini and realised by the engineer Gian Paolo Ferrari. The fact

that the trace of the new bastioned defence work had to follow the

profile of the hill top so closely meant that dissatisfaction was

frequently expressed by the Venetian military engineers about the short

comings of the new fortification, especially the narrow flanks to the

four bastions which protected the landward side.

Plan

late 17th century

Engraving 1717

Cost

constraints and a number of changes in plan meant that only a portion

of the new fortress was occupied, largely with important civil,

ecclesiastical and military buildings. The bulk of the population

rebuilt their homes on the lower ground adjacent to the fortress on the

SE. A number of impressive structures exist in town dating from this

latter phase of Venetian constriction, most notably the Loggia

constructed around the middle of the 16th century possibly to the

design of the military architect, Michele Sanmicheli. It has

been

suggested that as well as functioning as a meeting place the strongly

built rectangular structure as served as a detached fort in times of

need. Other relevant remains of the fortified town are the Rimondi

fountain on 1626, the much decayed remains of barracks associated with

the Santa Barbara Bastion on the SW corner of the town defences and an

arch marking the site of the once important Porte Guora.

Barracks at St Barbara Bastion

The Loggia

Porte Guora

The

Venetian fortress was finally put to the test in 1646 when the whole

complex was captured by the Turks after an outbreak of plague amongst

the defenders.

The

Turkish authorities undertook basic maintenance on the walls and

erected a large detached raveling to cover the approach to the main

gate from the east. During the following centuries a range of domestic

buildings came to occupy the interior of the fort which much diminished

its military capabilities. Clearance, repair and restoration began

after the Second World War.

Magazine

Prison and Mosque

Ramp to

Ay. LoukasBbastion

Visiting

Rethymno.

The town remains one of the most attractive in Crete but

becomes very crowded in the main holiday season. A modern and

attractive archaeological museum now occupies the Turkish ravelin which

while very interesting in its own right rather obscures the internal

arrangements of the defensive work. Entrance to the fortetza

is

by the ticket office situated inside the main gate. Access to all parts

of the fortress is freely available and there is considerable

restoration work still underway. The most impressive work done to date

includes the clearance and consolidation of the main magazine close to

the north wall and the repairs to the ramp and cavalier that dominates

the Ay. Loukas Bastion. Another striking monument is the

Mosque

of Sultan Ibrahim on the site of the former Cathedral. A complete

circuit of the defences is possible offering striking views over the

town and coast.

The site is in the

guardianship of the Greek Ministry of Culture and a useful guidebook is

available.

Bastion

of Ay. Loukas from E

Bastion of Ay.

Pavlos from W

Bastion of Ay. Nikolaos from S

17C view

17C view

Bibliography:

Castles of the Morea by Kevin

Andrews, Revised Edition, Princetown 2006

Venetians and Kinghts

Hospitallers – Military Architecture Networks, by Archi-med

Pilot Action, Athens 2002

Rethymno by S. Kaligeraki,

Mediterraneo Editions, Athens 2002

Fortresses and Castles of

Greece, Volume 3 by A. Paradissis, Athens 1999

The Fortetza of Rethymno by I.

Steriotou Athens 1997

Venetian

Fortresses in Greece at: http://romeartlover.tripod.com/Venezia.html