Relief Models of Venetian Fortifications at the

Church of Santa Maria del Giglio

Back to 'Fortified Places in Greece'

Church of Santa Maria del Giglio

Back to 'Fortified Places in Greece'

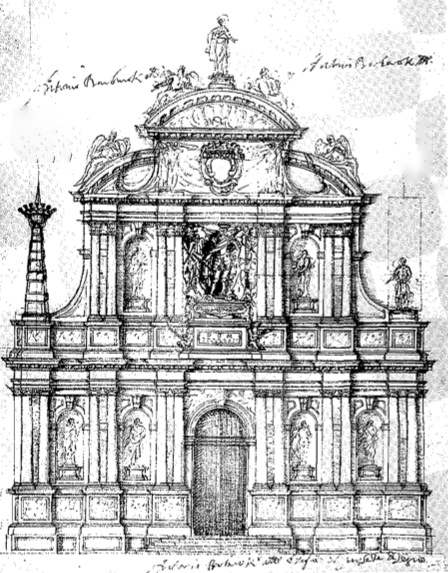

In

1689 the Venetian Admiral Antonio Barbaro died leaving detailed written

instruction and the sum of 30,000 Ducats for work on the facade of the

church of Santa Maria del Giglio (also known as Santa Maria Zobenigo)

in the Campo Santa Maria Zobenigo, west of the Piazza San Marco. This

remarkable baroque construction was erected with the sole aim of

glorifying the Barbaro family, much to the disgust of pious Venetians

who noted that there was not a single item of religious imagery

anywhere on the facade. A detailed drawing by the architect Giuseppe

Sardi was attached to the will making it clear that the entire

decorative scheme was approved of if not actually designed by the

admiral himself.

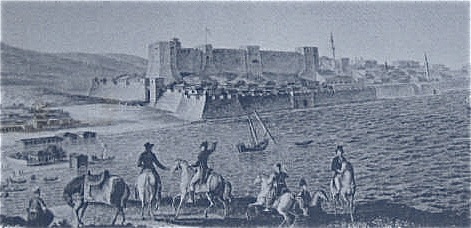

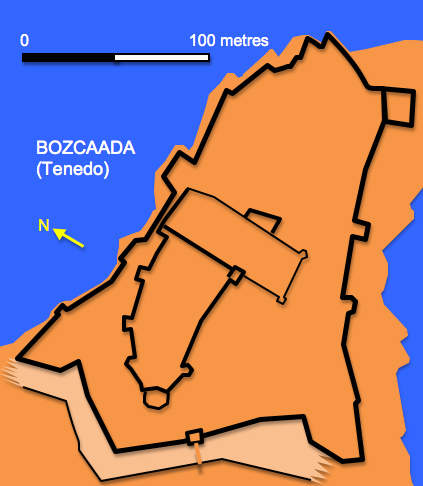

Antonio Barbaro was born in 1627 to a patrician Venetian family with a long history of service to the republic. He took part as a naval commander in many engagements against Turkish forces. In 1656 he fought bravely in an attack during which the Turks lost 84 ships and the island of Tenedo but was reprimanded for his unruly and undisciplined conduct.

Tenedo ( Bozcaada) from a 19th. century engraving and plan

Similarly in 1661 he was called before the great Venetian admiral Francesco Morosoni to answer charges of insubordination. In 1666 he was sent to support local forces during the siege of Heraklion and was responsible for amongst other things the fortifications. However, he returned to Venice the following year with further accusations and counter accusations hovering about him. Despite this in 1669 he was named governor of Dalmatia and Albania and in 1672 of Padova (Padua). After a disastrous period as ambassador to Rome from 1675 to 1679 he was recalled to Venice where he died in the same year. His turbulent career had involved him going against some of Venice’s most important families and it seems that his need both to justify and glorify himself and cock a snook at his enemies lay behind his extraordinary architectural commission.

A – Antonio Barbaro, B – Giovani Maria Barbaro, C – Marino Barbaro, D – Francesco Barbaro, E – Carlo Barbaro

1- Zara, 2 – Candia, 3 – Padova, 4 – Rome, 5 – Corfu, 6 - Spalato

As well as statues of himself, other members of the family and half a dozen panels showing naval engagements Barbaro also had six panels sculptured and set at ground level portraying six of the locations where he no doubt in his own eyes distinguished himself. These are in effect relief models of six fortified places and his military interests are emphasized by the fact that the actual fortifications figure strongly in the panels. The marble panels are around 2 metres long and a metre high and feature the following locations (moving left to right) across the facade:

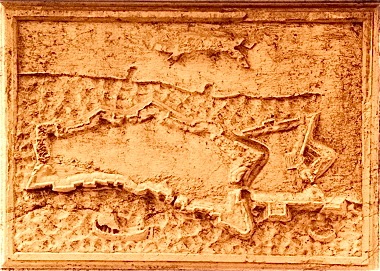

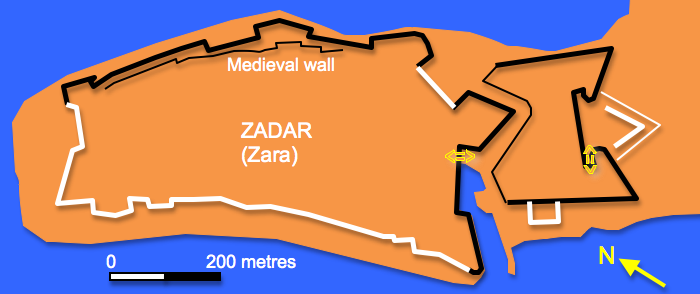

Zara (Now Zador in Croatia )

Zara had first come within the Venetian sphere of influence in the ninth century but in the eleventh century had returned to being a vassal of the Byzantine Empire. In 1202 the city was sacked by a combined Venetian and Frankish force at the start of the Fourth Crusade. In 1409 Venice purchased the right to the Dalmatian coast and occupied the city until their fall in 1797. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the town was subject to repeated attacks by the Ottomans and consequently the defences were strengthened until they took on the form shown in the relief which is oriented as if viewed form the south west. The peninsula on which the town sits is defended by three bastions joined by a curtain wall with a gate just to the west of the central bastion and beyond that and set slightly to one side a large hornwork

The town and its peninsula were also surrounded by a sea wall. The defences remain largely intact today. The carving shows no internal detail to the city except for a broad flight of steps leading up to the central portion of the hornwork but two vessels are depicted sailing off the coast. This is probably the most seriously eroded panel of the six.

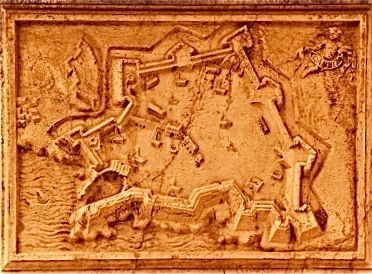

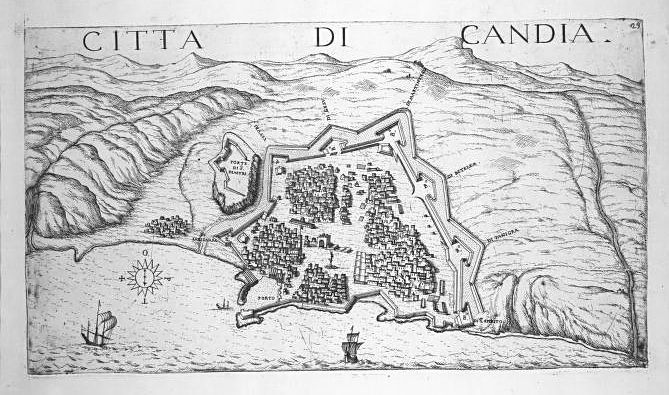

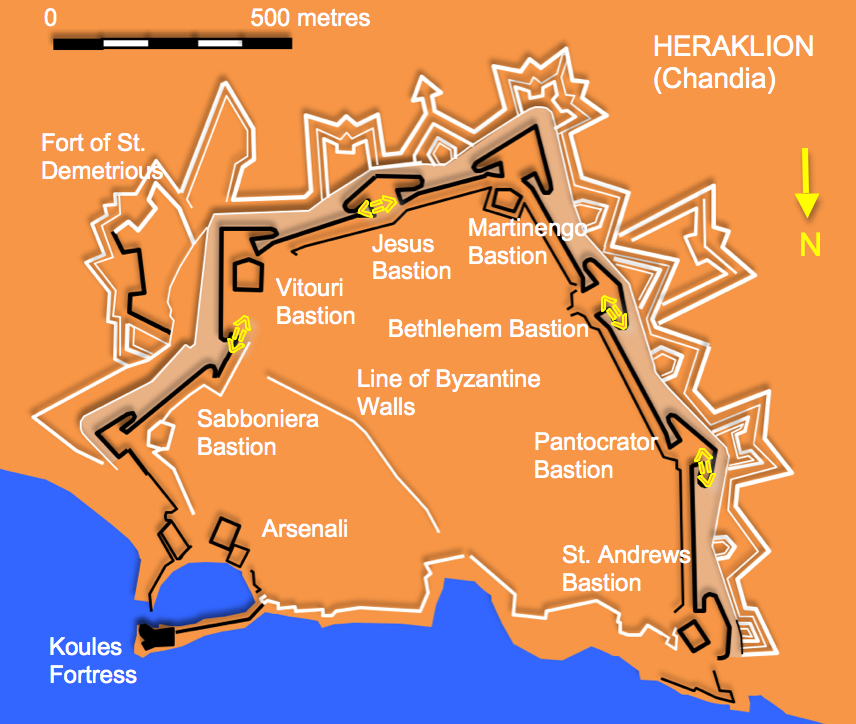

Candia (Now Heraklion in Crete)

We have already given an account of Candia ( see http://www.fortified-places.com/heraklion/ ). The relief is very similar to the plan depicted in Marco Boschini’s “Il regno tvtto di Candia. Delineato a parte”, published in Venice in 1651, right down to the small two masted ship entering the harbour. It also shares the same orientation as this map viewing the city from the north. The sculpture also clearly shows the harbourside ship sheds with their ‘corrugated’ roofs, cavaliers inside some of the bastions and a line of buildings possibly marking the line of the earlier town wall with a gateway. Also shown are the detached works of the Fort of St. Demetrious and other domestic buildings.

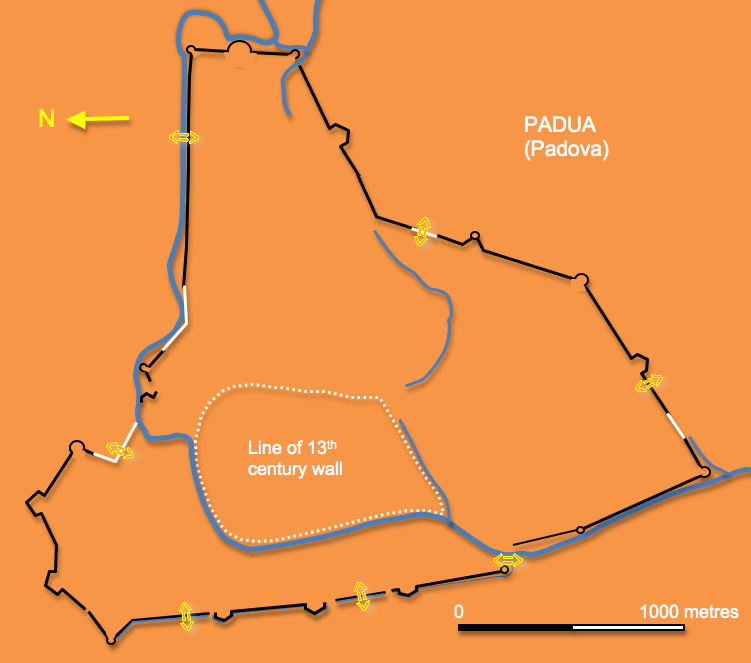

Padova (Now Padua in Italy )

Padua lies some 35 kilometres west of Venice and after a turbulent history came under Venetian control in 1405. After a brief reversal of fortunes the Venetians defended the city successfully in 1509 against forces lead by the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I. Considerable damage was done to the 14th. century Carraresi walls which were rebuilt over the next four decades to complete a circuit around 11 kilometres long. Some of the work was undertaken under the direction of the engineer Michele Sanmicheli.

Padova in 1704 by Blaeu

The relief viewing the city from the west clearly shows the medieval core of the city with its 13th century walls largely intact. A rectangular enclosure at the bottom right corner of the medieval city represents the castle and the massive Palazzo del Ragione stands out towards the centre. Other interesting structures shown outside the medieval walls include the circular botanic garden founded in 1545. The area outside the town wall is divided up into a patchwork of fields by a series of incised lines marking out the dividing drainage ditches.The walls which are on the whole in good condition and easily accessible are a mixture of small bastions with flanks set out perpendicular to the curtain and large low circular bastions. The town still has an impressive series of contemporary gates.

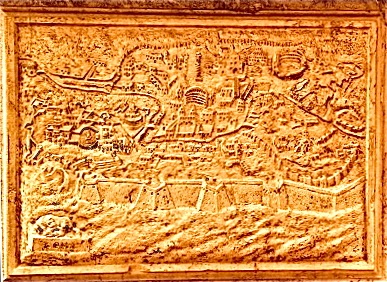

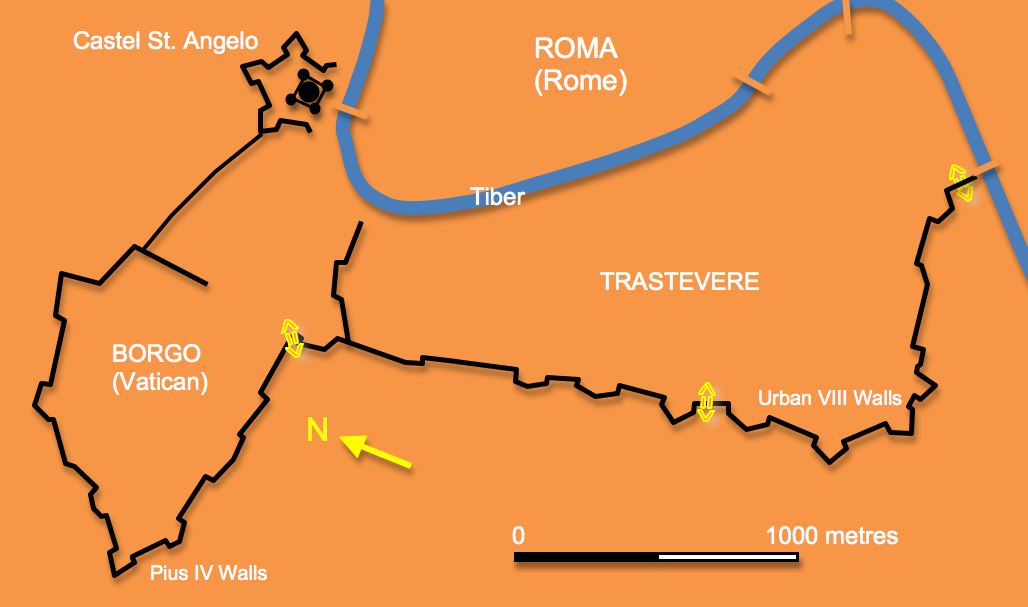

Roma (Rome – modern capital of Italy)

The panel devoted to Rome is more of an oblique view than a relief plan. The view is from the south west which ensures that the most prominent feature in the foreground is the wall and bastions along the ridge of the Gianiculum Hill. These works were erected on the orders of Urban VIII (1623-1644) to link the fortified area around the Vatican Palace, known as the Borgo with Trastevere. The Borgo itself is clearly delineated as is the Castello St. Angelo and its surrounding bastions. Paul III (1534-1549) defended the Borgo with bastioned walls whilst Pius IV (1559-1565) doubled the urban area of Borgo and enclosed this area with a wall anchored on the newly bastioned Castello St. Angelo. Towards the top right of the panel can be seen further elements of a bastioned trace erected by Paul III in an attempt to replace the full circuit of the late Roman ‘Aurelian’ walls, a project which was never completed. Otherwise the Roman and medieval walls are shown as a series of small rectangular towers strung along the curtain wall like beads on a wire. A number of important structures can be identified within the city including the Theatre of Marcellus, the steps up to the Capitoline Hill, Trajan’s Column and Market and of course the Colosseum. The seventeenth century walls of Rome remain very well preserved and present a magnificent if rarely visited spectacle.

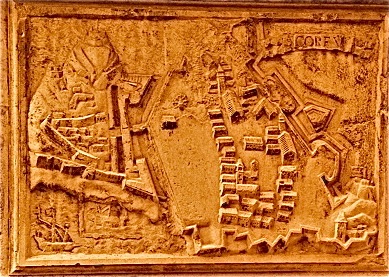

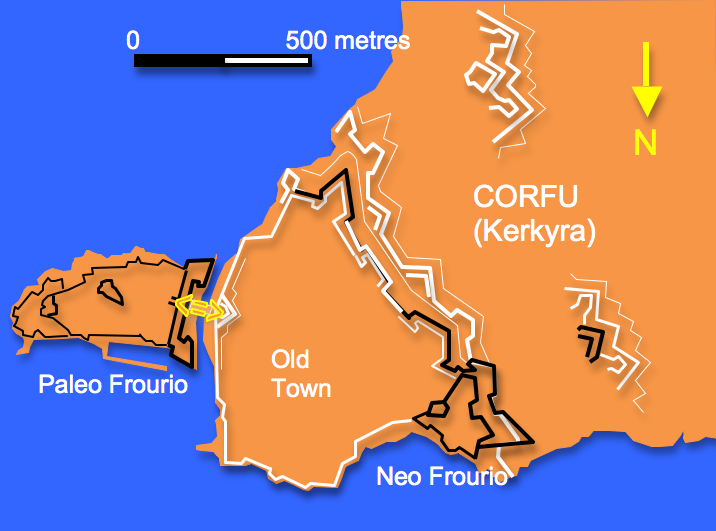

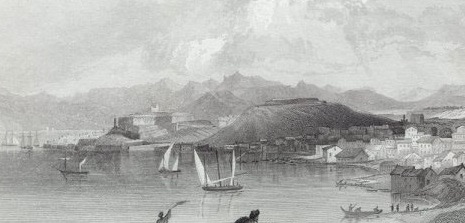

Corfu (Keryka in modern Greece )

.Corfu with its strategic position at the southern end of the Adriatic Sea was first occupied by the Venetians in 1401 having passed through a series of hands since was taken from the Byzantines in 1081 by the Norman Robert Guiscard. Venetian forces with stood a number of major attacks by the Ottomans most notably in 1537, 1571 and 1716. The first defences were built in the sixth century on two rocky outcrops on a peninsula which dominated the bay and harbour to the south and were maintained and extended throughout the middle ages. In the sixteenth century the land front was constructed with two bastions joined by a curtain with a central gateway all fronted by a sea water moat. Following the 1571 siege the developing town was further protected by a large fortification built on a hill just over a kilometre further west. This consisted of two large connected bastions fronted by a wide terrace. The town itself was also fortified by a trace consisting of a large shallow bastion, a central rectangular bastion, an acute angled bastion at the southern corner and a smaller bastion against the coast. This work was initially carried out by the engineer Vitelli, in the mid-seventeenth centuries these works were extended with outer trace containing two bastions and three demi-lunes and beyond them two detached earthwork forts.

The sculptor has had to resolve a number of difficult issues on this panel. The main defences of the old fort are shown in plan whilst the two rocky eminences which bore the earlier fortifications are shown in elevation, one behind the other. The view is from the north and the works of the new fort are sketchily shown crammed into the bottom right corner. On the other hand the northern most bastion of the town trace is clearly presented as is the demi-lune beyond it and the squared bastion next in line, however, lack of space means that the southern most defences are again quite restricted. In the bottom left corner are shown two galleasses, one under way and other in the harbour with its sail furled. The surviving fortifications on Corfu today are some of the best preserved and most impressive in the eastern Mediterranean.

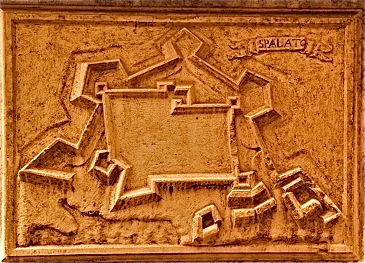

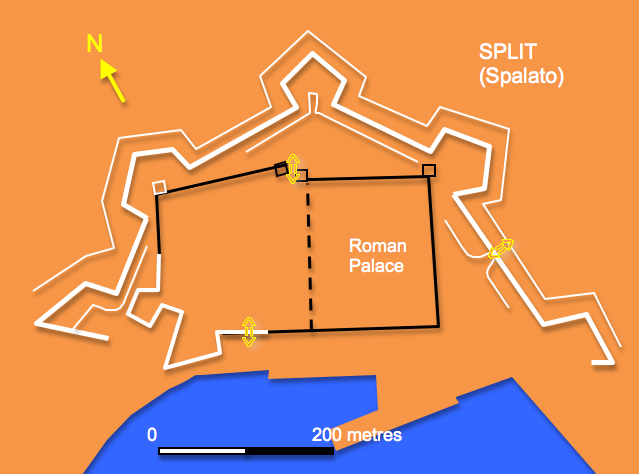

Spalato (Split in modern Croatia )

An enormous palace was built here by the Roman Emperor Diocletian in 293 AD for his retirement and later formed the shell within which the early medieval town grew. The Medieval period in Split is marked by the waning power of the Byzantine Empire, and by the struggle of the neighboring states, namely the Venetian Republic, the Kingdom of Croatia, and (later) the Kingdom of Hungary, to fill the power vacuum. Having purchased the ‘rights’ to Dalmatia the Venetians moved in 1420. The port was extensively developed in the late 16th Century for Venetian trade by a Levantine Jewish merchant named Daniele Rodriga. The defences were modified and extended in the late 16th century and again in the mid 17th century before being almost completed demolished in the 1800’s. The relief panel views the town from the south and shows a rectangular inner enclosure made up by the roman walls and square towers to the right and medieval walls and towers to the left. In addition there is a large triangular bastion on the south west corner with a small pentagonal bastion to the north. An outer line of defence creates a roughly pentagonal enclosure with a longer side being made up by the water front. Two large triangular bastions flank this and there are three slightly smaller pentagonal bastions shown defending the rest of the circuit. A handful of large buildings are shown at the harbourside presumably warehouses and ship sheds. Whilst the Roman and medieval defences remain well preserved most of the later work has been swept away apart from a few traces preserved in a park and in elements of the street plan.

Although unique in their ostentation other carved relief sculptures of fortifications are known in Venice. There are carvings of the siege of Candia in the mausoleum of Alvise Mocenigo in the Church of St. Lazarus of Mendicoli, images of S. Mauro and Cephalonia on the Sarcophagus of Benedict of Pesaro and views of Smyrna and Cyprus on the funeral monument of Doge Pietro Mocenigo in the Church SS. Giovanni e Paolo

The Naval Museum in Venice has a collection of 18 models of Venetian strongholds from the sixteenth and seventeen centuries. Originally kept in the Arsenal they are made of wood, papier mache and plaster and were restored in 1872 and more recently. Some models in the collection are:

Fortress of Chania - Year 1608

Castle at the mouth of the port of Heraklion - 1620

Cliff Grabosa in Heraklion - 1620

Scoglio S. Theodore in Heraklion - 1625 (Fortress Spinalunga)

Fortress of Kythira - 1707

Fortress Carabus - 1614 (Islet of Spinalunga)

Fortress Spinalunga - 1619 (Fort Botticelli in Split)

Fortress of Famagusta in Cyprus - 1571

Mama Morea - 1686 (Fortress Details Famagusta)

Fortress of Naples of Romania - 1625 (Zante)

Fortress Suda -1612

City and Fortress Zara -1612

Candia -1612.

Castle at the mouth of the port of Heraklion - 1620

Cliff Grabosa in Heraklion - 1620

Scoglio S. Theodore in Heraklion - 1625 (Fortress Spinalunga)

Fortress of Kythira - 1707

Fortress Carabus - 1614 (Islet of Spinalunga)

Fortress Spinalunga - 1619 (Fort Botticelli in Split)

Fortress of Famagusta in Cyprus - 1571

Mama Morea - 1686 (Fortress Details Famagusta)

Fortress of Naples of Romania - 1625 (Zante)

Fortress Suda -1612

City and Fortress Zara -1612

Candia -1612.

Two others have been lent to the Museum of Military Engineers in Rome.

Relief plan of Famagusta in the Venetian Naval Museum

The use of relief modelling for military purposes may have originated with Italian military engineers during the fifteenth century. Pope Clemens VII used a cork model of Florence created by Benvenuto di Lorenzo della Volpaia and Niccolo Tribolo to plan his siege of 1529. The first centre of relief modelling became Venice in the middle of the 16th century. Originally nearly 200 models were created to depict the possessions of the Venetian Doges in the Levant.

The close resemblance between the carved image of Heraklion and the pictorial map of Boschini published in 1651 has already been mentioned. The panel for Rome shares a viewpoint with a 1658 engraving by Janssonius. The appearance of the panels suggests that they were based on similar printed maps rather than from observations of the more technical relief models kept in the city. The printed maps which may have been used could have come from a number of different sources thus explaining the variation in approach between the panels, for example the limited internal detailing for the Dalmatian sites and the striking use of elevation for the Corfu carving.

Plan of Rome by Janssonius 1658

A detailed report on the history of the church and its restoration printed in 1969 for the World Monuments Fund can be found at :

http://www.wmf.org/dig-deeper/publication/church-santa-maria-del-giglio

An account in Italian of the relief models is at:

http://www.iapad.org/history_serenissima.htm

A useful audio-visual tour of the church is at:

http://www.museumplanet.com/tour.php/venice/gig/0