Back to Introduction and Contents

The last two

months of 2015 were given over mainly to producing reports arising from

commercial work that had been undertaken including the two jobs for the

National Trust detailed in the the coverage for earlier months. In

addition a private commission for work on a house in Northamptonshire

also had to be written up so it's no surprise that there was not a lot

going on out and about in the run up to Christmas. We did undertake

some back-filling in the sunken garden to enable the snowdrops to be

replanted where necessary.

After a final clean up the walling along the eastern edge of the Sunken garden was photographed and Peter completed the planning then it was on to the backfilling, Peter tramples it down.

After a final clean up the walling along the eastern edge of the Sunken garden was photographed and Peter completed the planning then it was on to the backfilling, Peter tramples it down.

Then just before Christmas I was

contacted by University with the news that my application for transfer

of status (it's an Oxford D.Phil. thing) had to be in by the 20th. plus

5,000 words or so of relevant specimen prose. Well, that wasn't

going to happen so after a certain amount of negotiation we agreed that

it could all be handed in on the first day of Hilary term so that saw

much of January similarly spent at the keyboard. You can see the text

of this offering below. Then as the end of the month approached we were

back in action at Farnborough getting geared up for a major project. You can read all about it here.

Back in Farnborugh, the Cascade is given a wash and brush up.

Back in Farnborugh, the Cascade is given a wash and brush up.

Prologue

In the seventeenth century Oxfordshire was home to three remarkable gardens: Wadham College, Hanwell Castle and Enstone, site of the Enstone Marvels. In the finished thesis it will be argued that these gardens, through the medium of the people associated with them, played a role in the development of a way of working and indeed thinking which was later characterized as the Scientific Revolution. However, to establish this as being the case, it is important to understand the place these sites occupy in the general history of gardens and specifically the ways in which technology was expressed in the design and functioning of gardens. Hitherto garden history has been the largely a product of the views of art historians who have given the study a very specific focus and in the process have under-emphasised some of the social, cultural and technical significance of gardens, a situation which can be partly remedied through archaeology.

One could give an account of popular misconceptions along these lines… Garden history is easy. The Romans had gardens and some got buried. In the middle ages the Romans were forgotten about and gardens were little square plots and all about courtly love and medicinal herbs. Then came the Renaissance and the Italians dug up the Romans and a few books and copied them and we copied the Italians… and then the French… and then the Dutch and everything was terribly formal until Capability Brown came along and made the world safe for future generations of film producers wishing to shoot Jane Austen movies. In fact the English parkland style was so self-evidently superior it took over the world. Oh and then there was someone called Gertrude something who did something grey with her borders.

Although this is a caricature it captures something of the way in which garden history has been profiled in countless guidebooks and other popular publications. Like all caricatures there is, of course, an element of truth buried within it but so much is based on errors of one kind or another that it is, at heart, fundamentally misleading.

Garden History and Archaeology

The history of gardens has been written primarily by art historians and this simple fact has had a profound effect on our understanding of how gardens have developed and their importance in a wider cultural and social setting. Research over the past 25 years has revealed how flawed that understanding can be. The common assumption was that if gardens are essentially works of art then there must be an artist or at least a designer behind them and that all gardens must equally have a programme based on a recognizable and understandable iconography. Landscape architect Rafaella Giannetto has written extensively on this and has pointed out that one of the key locations used by garden historians in proclaiming the birth of the Renaissance garden ideal and its literary antecedents, the Villa Medici at Fiesole, has been misread on both historical and archaeological grounds (Giannetto 2008). From an historical point of view the chronology is all wrong and she has established that the gardens were essentially complete several decades before their purported designer came on the scene. In fact she shows that most of the early gardens in her study were the product of those craftsmen charged with management of the estate whose work was drawn into later theoretical constructs. It is an important point that will link with future analysis of seventeenth-century technology in that her concept of the artisan designer chimes with some of the recent archaeological work done on early scientific instruments where it is clear that workmen were manufacturing sophisticated measuring devices up to half a century before their assumed ‘inventors’ first wrote about them (Johnston, S. 2013).

Her archaeological perspective has allowed her to demonstrate that a number of key features which have been designated as being Renaissance garden archetypes were not constructed until the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries (Fig. 2). She further notes that, ‘writings on the most popular of the Florentine gardens tend to reiterate information that is often taken for granted and accepted without reservation’ (Giannetto 2008:ix). In a more radical challenge Lazzaro argues twentieth-century views of Italian garden history are primarily a by-product of fascist ideologies (Lazzaro 2005). Gianetto’s more empirical approach to garden history has been championed by archaeologists in the United Kingdom and United States who have, as we shall see, reshaped our understanding of medieval gardens to a remarkable degree.

Fig. 2 the Medici Villa at Fiesole, view from south east. Some of the terraces and walkways have been shown to be later additions.

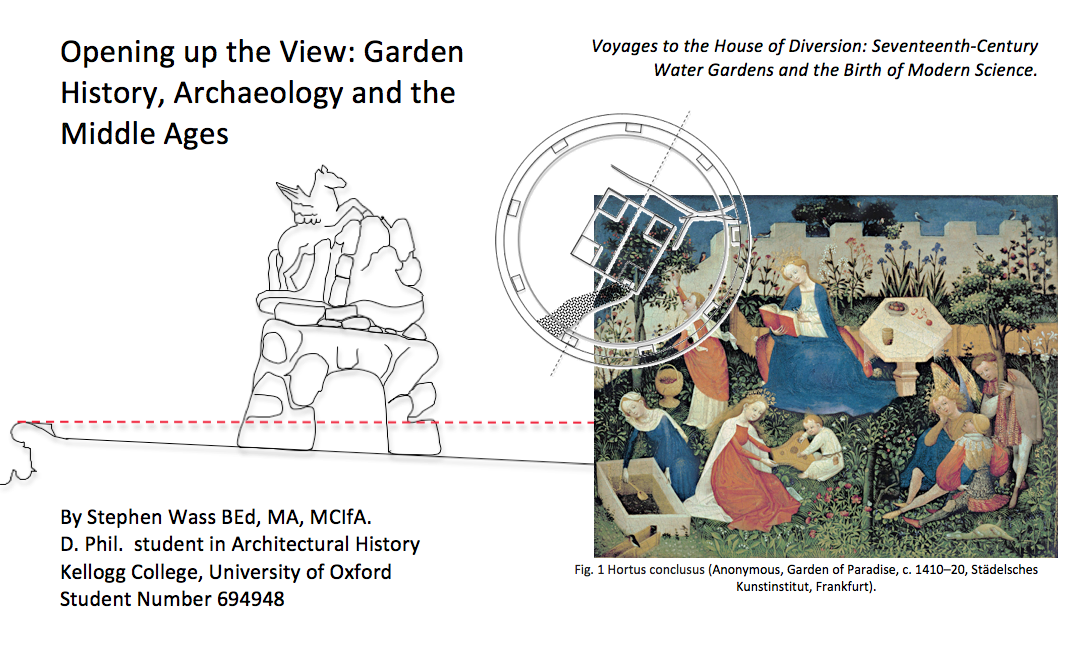

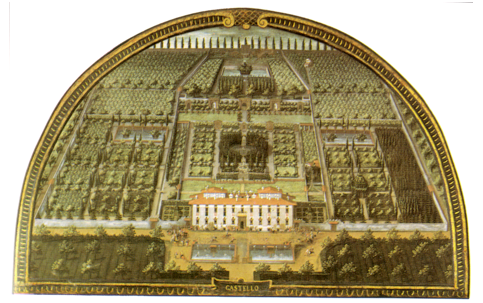

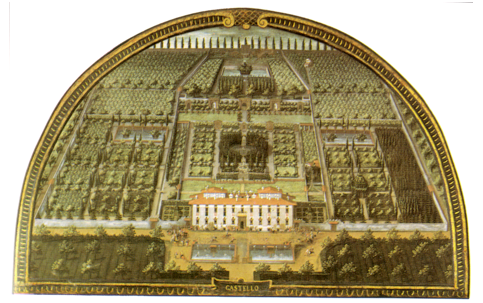

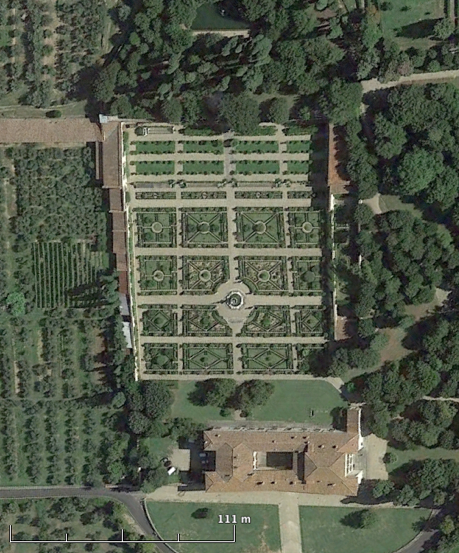

Many of the most trenchant criticisms of art history have been made by art historians themselves. Rabb and Brown comment on the difficulties implicit in the fascination for ‘hidden messages, in teasing out the complex implications of symbols, mental patterns and cultural structures’ yet underscore ‘the hope for the tangible and the concrete’ (Rabb and Brown 1988:2). The primacy of images in art history in general and the study of historic gardens in particular is perfectly understandable, why get mud on your boots when the whole scheme of things is displayed in this painting or that estate plan? The fact is that images in this context can be profoundly misleading for three reasons. Firstly they give a distorted view of the generality of gardens by shifting the collective gaze onto a particular group of elite gardens. The richer and more admired the patron the more likely they would have been to have illustrations commissioned of their properties. Secondly such illustrations are then subject to the editorial control of both the patron and artist so that the portrayal may be flattering to the original and influenced by aesthetic principles so that particular features within the garden are relocated simply to make a better picture (Figs. 3 and 4). This in itself is not without significance as Halpern says, ‘They [ the images ] tell us what mattered to the villa owners, and in many respects they are most interesting in their contradiction of reality’ (Halpern 1992: 183), Ribouillault amplifies the point, ‘images of gardens which were previously considered to be “documents” are now starting to be studied as “monuments” ‘( Ribouillault 2011: 204). Any account which builds elaborate theories about space, time and perspective on images of gardens alone must be suspect. Finally further complications arise when illustrations of planned proposals are treated as if the features were actually built which was quite frequently not the case (Currie 2005:27).

It is obvious that garden history would not exist without art history and much of what has been written over the past century constitutes an essential part of the study of gardens but many gardens, actually most gardens, lack the kind of source materials that makes them accessible to this kind of investigation and so the particular contribution that archaeology can make comes to the fore. The criticism has been made in the past that the use of archaeology to study the historic past is ‘the most expensive way in the world to know something we already know’ (Deetz 1991:1) but then archaeology goes on repeatedly to deliver the goods when it comes to new understanding of the recent and not so recent documented past (See for example Tarlow and West 1999 and Hall and Silliman 2006 ). It does this by drawing on a variety of techniques to expose the material remains of the past. In the context of gardens this includes survey, notably of earthworks, analysis of aerial photographs, geophysics and in some cases excavation. This data is then subject to what Gleason describes as, ‘The ever expanding variety of analytical techniques available to archaeologists to help reconstruct the spatial and perceptual environment people would have experienced in the built landscape’ (Gleason 1994: 3). Archaeologists may be deluding themselves to a certain extent in their claim to scientific objectivity and only dealing with facts but there is no doubt that archaeological input can have the effect of nailing theoreticians’ feet to the ground.

Fig. 3 Villa Medici at Castello, lunette by Giusto Utens from 1599 from the Villa Medici at Petraia, note the strongly symmetrical layout.

Fig. 4 Aerial view of Villa Medici at Castello from Google Earth showing the true asymmetric arrangement of villa and gardens

An extraordinary instance of the tendency to theorise in the absence of all the facts is the flood of scholarly articles that have followed the ‘rediscovery’ of the Sacro Bosco at Bomarzo, Italy in 1947 by the surrealist Salvador Dali and critic Mario Praz (Morgan, L. 2012). Remarkable by any standards this site might today be termed a sculpture park. Scattered around a fairly limited area are a number of huge figures carved out of natural boulders of the local peperino stone lining a narrow stream cut gorge. Constructed between 1550 and 1580 by retired soldier Vicino Orsini the garden has inspired almost as many interpretations as there are commentators. Literary inspiration is claimed for Colonna’s Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1499), Aristo’s Orlando Furioso (1532) or Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata (1581). (See summary in Darnall and Weil 1984). The futility of all this effort is captured by Cody, ‘the bosco’s ability to attract all manner of iconographic or programmatic readings while ultimately partaking of none, seemingly explains the near total lack of analytical or interpretive consensus within the last sixty years of scholarly inquiry (Cody 2013: 124). A particularly interesting proposal by Scheeler is that the slightly tipsy stance of a Pegasus poised unsteadily upon a token Mount Parnassus is that this reflects Orsini’s conviction that the full body of learning itself stood on uncertain ground (Scheeler 2007: 56). In fact a careful examination on the ground reveals that the whole stone basin supporting the fountain has cracked away from the bedrock and slumped to one side almost certainly as a result of an earth tremor (Fig.5). Sharp has gone even further proposing an entire programme of water powered automata installed as an aid to seduction (Sharp 2015). Archaeological examination of identified features showed them to be mainly lavatoio (washing places) or drinking troughs (Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 5 Bomarzo, The Pegasus Fountain view from west, the crack can be seen on the left hand side.

Fig.6 Bomarzo, lavatoio view from south east – not a housing for automata.

Medieval Gardens

In attempting a brief history of gardens we need to pay due attention to the basics, so until the advent of modern materials and technologies the ingredients available for garden making have been essentially the same: rock, earth, water and of course plants. The permutations within these ingredients are both limited and infinite so a hillside can be either sloping or stepped, few options, but within that limitation many different configurations are possible. Hence it is that something like terracing on its own as a stylistic trope is of limited use for what else are you going to do on a sloping site? In addition England with its preponderance of clayey soils and frequently more than ample supplies of water is a land where no gardener operating on a large scale can afford to be ignorant regarding the management of water. A further consideration may be that the best way to identify foreign influences, especially south European, is by picking out those elements which are clearly unsuited to the British climate; it rarely makes sense to soak your visitors to the skin over here but those kinds of giochi d’acqua (water games) are perfectly suited to a summer’s day in Italy. Archaeologists know that gardens don’t stand alone but must be considered within many contexts ranging from the geological to the political but as we have already noted, this has not always been the case.

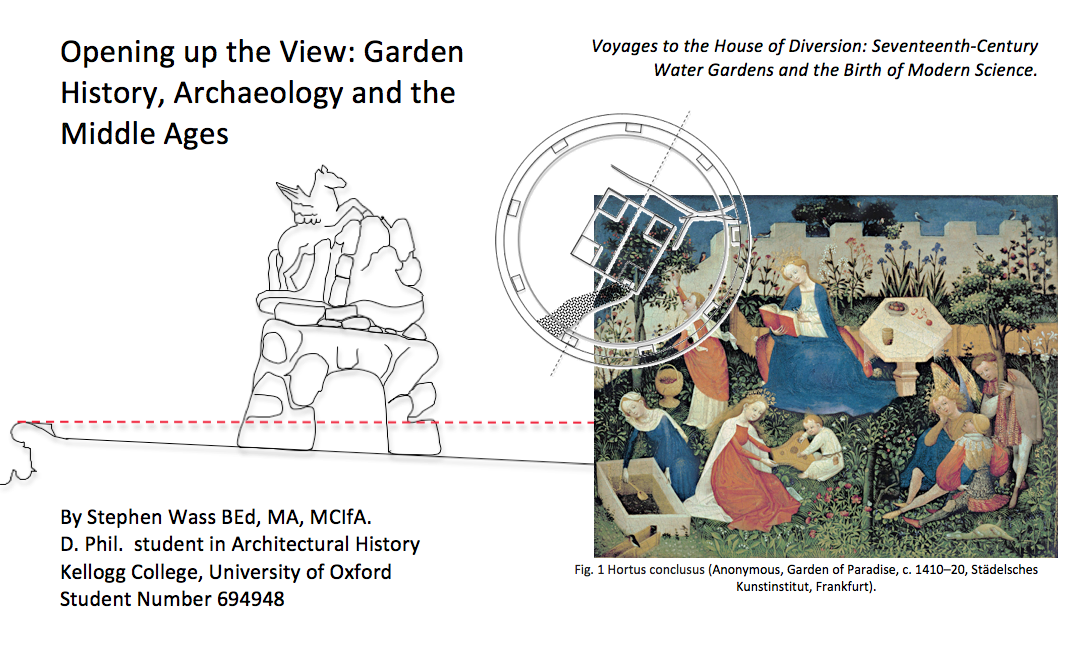

It is troubling that in his admirable and comprehensive ‘The Civilization of Europe in the Renaissance’ Hale could note that, ‘It was not until the mid-fifteenth century that actual gardens began to be developed as amenities that deliberately expressed social and aesthetic ideas (Hale 1993: 520). Writing as recently as 2012 Louise Wickham could still maintain of the early Renaissance that enclosed medieval gardens, Hortus conclusus were ‘opened up by new ideas inspired by classical models’ and that ‘this was the first time that gardens had used borrowed scenery since Roman times’ (Wickham 2012: 62). Again, over reliance on images has warped our views of medieval gardens (Fig. 1), as Currie points out, the compressed perspectives of medieval illustration affected perceptions that medieval gardens uniformly consisted of small closely bounded spaces (Currie 2005: 9).

At the core of any study of medieval parks, gardens and managed landscapes lies the castle. There has been a really significant move away from regarding castles as military mechanisms to a much more nuanced appreciation of their role as administrative, social and cultural hubs which formed a back drop for economic, political and technological display, what Liddiard calls ‘courtly choreography’ (Liddiard 2005: 51). Goodall in his magisterial survey of English castles suggests that, ‘discoveries and research over the last twenty years… have reformulated the received understanding of the castle to the point of revolution’ (Goodall 2011: xvii) and this applies as much to the landscapes around them as to the buildings themselves. So, although a comprehensive history of medieval gardens in Britain has yet to be written, ample work has been dome on many individual sites and it is possible to begin a synthesis by examining some individual case studies. As we shall see there is much evidence for extensive and sophisticated developed landscapes in England from at least the twelfth century onwards. Indeed the Norman conquest is an appropriate place to begin; evidence for early Norman settlement is plentiful and the Gens Normannorum bought a degree of sophistication across western Europe from Ireland to Sicily. There are many instances of early Norman estates where the layout of castle, gardens and park clearly demonstrate the ability to use locations to make points about dominance and subjugation whilst at the same time creating a landscape that is productive and beautiful.

At Restormel in Cornwall the castle was established around 1100 by the Cardinham family (Salter 1999:32). Its location has many points of interest (Fig. 7). It is certainly not the most defensible spot in the area which actually lies to the south west and is occupied by the site of a Roman fort, nor is it close enough to offer protection to the town and bridge at Lostwithiel but it is intervisible with the town and the surrounding countryside which by the mid-thirteenth century had become a elaborate park under the control of the Earls of Cornwall. In his analysis of the landscape Creighton describes how, ‘the building was ‘keyed into’ a local setting that was manipulated, at least in part, with an eye for aesthetic value, thus amounting to a designed landscape’ (Creighton 2009: 17). Features included a mill and hermitage set on the banks of the Fowey below the castle and the careful alignment of the park boundary so it is, in effect, invisible from the castle creating the illusion of a much larger estate. Particularly noteworthy is the circular wall walk on the castle which seems designed for promenading and appreciating the view, it makes poor sense defensively. Now it may be argued that aspects of this are simply an over-interpretation of fortuitous juxtapositions within an entirely functional landscape but these ideas can be seen further developed at Kenilworth where the physical efforts to transform the landscape were enormous.

Fig. 7 The park at Restormel (after Creighton 2009). Inset aerial view of castle (Google Earth).

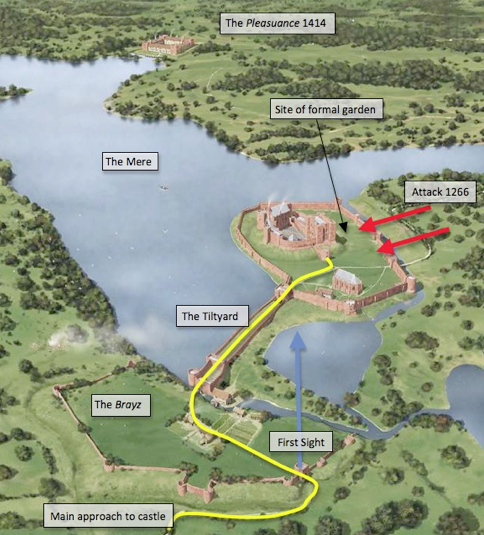

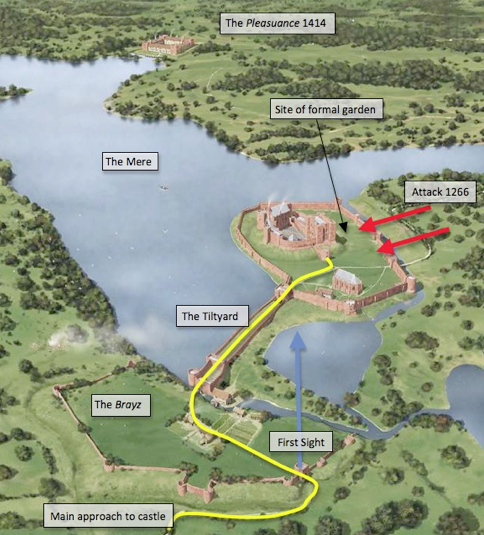

Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire was also begun in the twelfth century. From a study of contemporary charters Liddiard contends that the founder Geoffrey De Clinton defined a designed landscape of multiple components which formed the setting for four centuries of refinement (Liddiard 2005: 120). Examination of the castle’s plan as it stood prior to the famous siege of 1266 is instructive. A huge dam lay to the south of the main castle enclosure with further dams to the east which created an extensive mere that surrounded the castle on the south and west sides (Fig. 8). According to earlier accounts this defensive work was further protected by a massive crescentic earthwork known as the Brays (Thompson 1982: 25) and together formed one of the most sophisticated examples of military engineering seen in the country. In practice this huge investment makes little sense militarily as it could be simply ignored by mounting an attack on the weakly defended northern side of the castle. Further developments in the thirteenth century underlined the true nature of this complex as a grand ceremonial entrance to the castle with a staged unfolding of what was in effect a landscape of pleasure and beauty, when approaching from the south the view is blocked by the Brayz and only starts to unfold once one has passed through the first gate. In 1374 instructions were given to create an enclosed garden which may have been on the site of the Elizabethan garden created in the early 1570s (Demidowicz 2013: 33). This investment continued, in 1414 Henry V ordered the construction of a pleasaunce north east of the castle, a large rectangular moated site enclosing gardens and pavilions all approached by boat across the mere and into a dock.

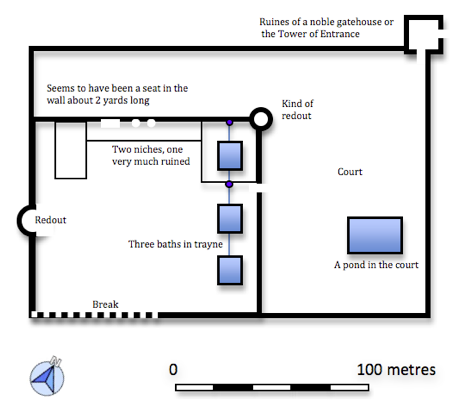

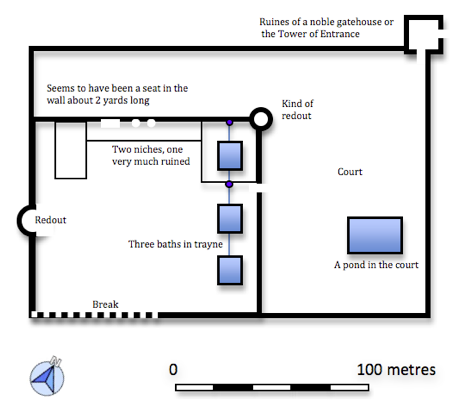

This idea of a separate enclosed garden or pleasance finds earlier expression in the feature later known as Rosamund’s Bower at the royal palace of Woodstock. This garden based on a water source known as Everswell lay around 300 metres to the west of the palace. The surviving remains are fragmentary (Fig. 9) but John Aubrey sketched the ruins in the seventeenth century enabling a tentative reconstruction to be imagined (Bond and Tiller 1997: 46). We have a walled garden with an entrance tower a series of interconnected rectangular pools and walk ways with seats and niches (Fig. 10). The particular significance of this site is its early date, the 1170s and the possible design links with the Sicilio-Norman tradition of palace and garden building. The fact that there were dynastic and cultural links at the time with both Sicily and Iberia is well established (James 1990: 54) and Colvin in his exhaustive History of the Kings Works refers specifically to the palace of La Zisa in Palermo (Colvin 1963: 1015). The Islamic garden works surviving in Spain are well known but the remains of a series of elite buildings originating with the Norman kings of Sicily are less familiar largely because they have been absorbed into the ramshackle suburbs of the city (Fig. 11).

Fig. 9 Blenheim Park, Rosamund’s Well, view from south.

Fig. 10 Twelfth-century enclosed garden and pools at Everswell based on annotated sketch by John Aubrey.

Fig. 11 La Zisa, Palermo, view from south showing foundations of pool and pavilion.

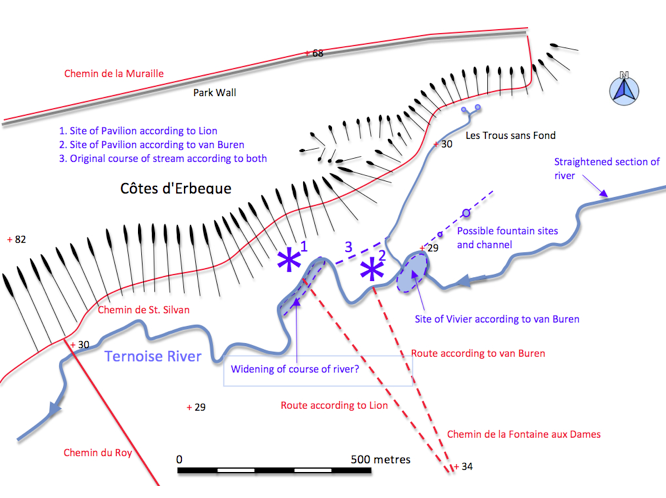

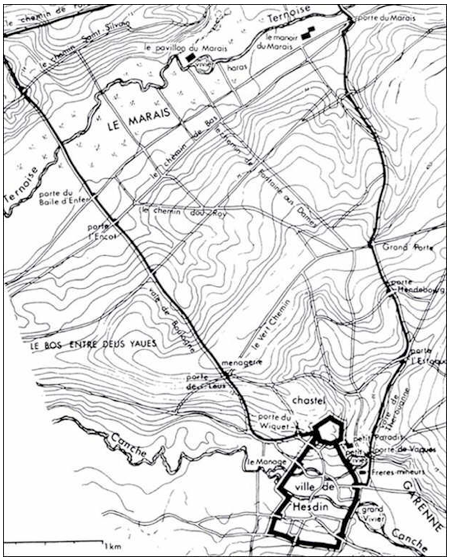

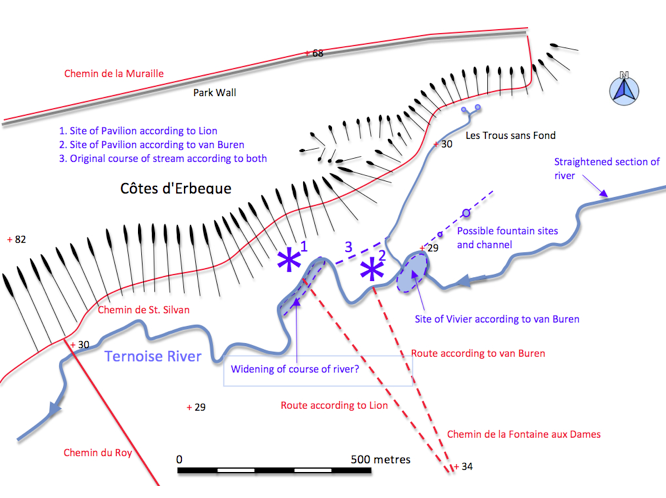

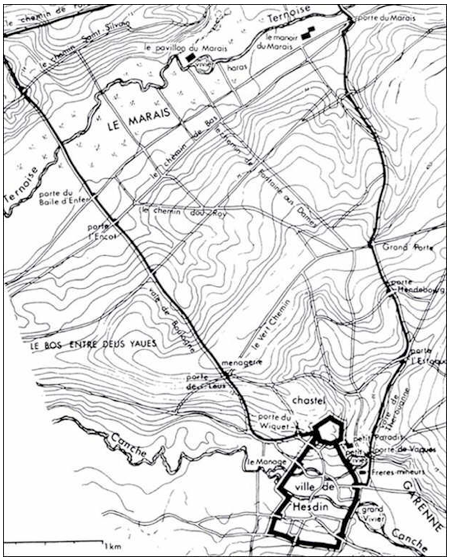

A further example of Islamic influence combined with local practices existed at Hesdin, today located in northern France. Here in the latter part of the thirteenth century was created one of the most elaborate and extensive parks of medieval Europe. Robert II Count of Artois, on his return from foreign parts, most notably Sicily, brought along with him cohorts of southern Europeans, including Italians, and commenced work on extending and improving the park attached to his castle and town of Hesdin (Now Vieil Hesdin). The scale of this undertaking was huge as was the time and expenditure devoted to the construction of assorted fountains, pavilions and entertaining automata (Farmer 2013) . Some of these were incorporated into the castle but others were scattered around the park, especially in a marshy valley to the north. The automata in particular have attracted much attention (For example Tronzo 2014: 101 – 10 and Truitt 2015: 122 – 37). They are significant because they represent the kind of feature normally associated with later Renaissance gardens in what is termed the Mannerist style and because there is general acceptance their origins lie in Arabic and Byzantine prototypes. There is less agreement on the exact means of transmission, but whether through written texts or personnel they illustrate a high level of planning and management in an era before, in some people’s view, garden history begins. In the case of the famous Marsh Pavilion we see a fusion of north European technology developed through the construction of timber bridges and water mills with more exotic mechanisms whereby the bridge to the pavilion was enlivened with nodding and waving monkeys clad in badger fur. As an aside it is worth noting that many of the debates about the functioning of the park have centred around its layout which was largely reconstructed from documentary evidence (Fig. 13 van Buren 1986: 128) on the ground some conclusions are demonstrably false, for example as relating to the actual location of the Marsh Pavilion (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12 Landscape analysis based on field work relating the position of the Marsh Pavilion.

Fig. 13 Reconstruction of he Park at Hesdin based on documentary evidence (van Buren 1986).

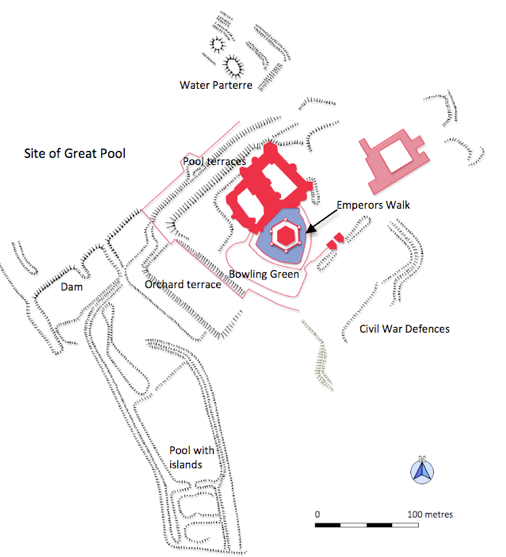

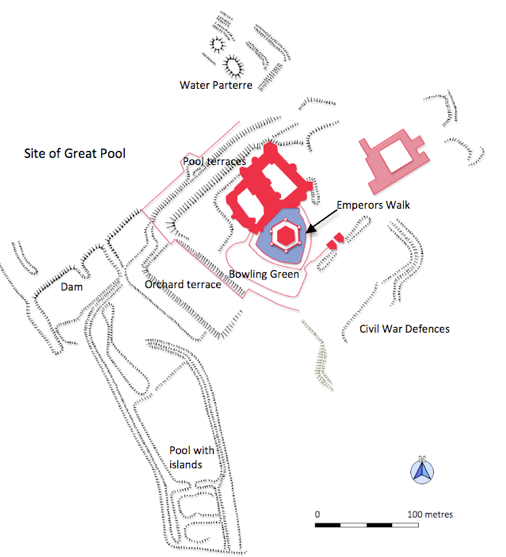

Throughout the middle ages we see examples of large and small scale undertakings whereby ground is cleared, terraced and planted for effect, enclosed gardens are built and extensive systems of waterworks are incorporated into a grand scheme of improvement and enhancement of the landscape. This is far removed from the established view of medieval gardens and demonstrates the fact that there was a well established and sophisticated tradition of garden and park construction well before the advent of the Tudors. The degree of continuity between medieval landscapes and Tudor gardens can be illustrated by examining the works at Raglan Castle, Gwent. Whittle writing in 1989 adopts the conventional explanation that the extensive gardens still visible as earthworks today are a phenomenon of the Renaissance, ‘made around the existing castle between 1550 and 1646 by the 3rd., 4th. and 5th. Earls of Worcester’ (Whittle 1989: 83). However, a building programme initiated in 1465 lead to the creation of two courts enclosed with towers and a curtain wall lined with accommodation blocks and the truly colossal ‘Yellow Tower of Gwent’, a free standing structure of some magnificence (Goodall 2011: 368). It is difficult to believe that works on a comparable scale would not have taken place within the associated park. Whittle states that, ‘there is some evidence that there were gardens of a utilitarian nature at Raglan in the fifteenth century. A “Fysshe Pole” is mentioned in an inquest in 1465 and an early fifteenth century manuscript states of Raglan “… about the palace there were orchards full of apple trees and plums, and figs and cherries and grapes, and French plums, and pears and nuts, and every fruit that is sweet and delicious” ‘ (Whittle 1989: 83). The assumption of simple utilitarianism is interesting and as we have seen largely debunked by more recent scholarship. Although there is no hard and fast dating evidence it seems likely that the great pool to the north of castle was a late medieval construction as was the terracing to the west of castle, an ideal location for the orchards described (Fig. 14). The long pool to the south west with two rectangular islands at its southern end also seems to owe more to medieval methods of construction that those of the seventeenth century. Much is made of the terracing between the castle and the valley below as being a typically Renaissance feature yet examination on the ground reveals that the earlier fabric of the building hanging, as it does, above a narrow gorge to the east could not have been built without the support of said terracing (Fig. 15). It’s perfectly possible that additional features such as stone steps, a balustrade and summer house were added post-1550 but the earth-moving had already been completed. The point at which Renaissance influences come roaring in is possibly under the direction of Edward Somerset, the 4th. earl who is believed to have commissioned a series of shell lined niches around the perimeter of moat surrounding the great tower (fig. 16). These formerly held statues of Roman emperors but like other features, a water parterre for example, were elaborations upon a landscape already fixed in the fifteenth century. General surveys of late medieval castles with significant continuation through the sixteenth century continually demonstrates the ‘bolt on’ nature of Renaissance additions.

Fig. 14 Raglan Castle environs earthwork details taken from 1976 OS 6 inches to the mile map.

Fig. 15 Raglan Castle, terracing below the north tower view from south west.

Fig. 16 Raglan Castle, the Emperors Walk view looking north.

In this brief examination of medieval landscapes we have concentrated on sites associated with the very highest echelons of medieval society and so fallen into one of the traps already identified as a weakness for garden historys in general. To open up a slightly broader perspective it is important to consider what evidence there is for gardens and landscapes associated with the lesser nobles and gentry. The moat is a significant feature which can be used to demonstrate continuity in approach to gardens oflesser status throughout the middle ages and into the early modern period. Archaeology provides much of the material for this and interest centres on that category of field monument known as the homestead moat. The familiar presence of moats around many castles extends to lesser constructions and many people are familiar with the way in which moats enclose domestic structures as at Baddesley Clinton, Warwickshire (Fig. 17) or Harvington Hall, Worcestershire. What is less well known is that huge numbers of moats exist, estimates suggest more than 5,000 survive (Aberg 1978: 3), simply as earthworks and free of any standing structures. They can be found in a broad swathe, largely across the midlands of England. Traditionally these were explained in terms of the kind of well known sites mentioned above as essentially former locations of medieval manors, granges or important farmsteads and excavation on the whole supported this assumption. However, archaeologists were puzzled by instances of multiple moats in close association and by the number of ‘empty’ moats that were excavated (Le Patourel 1978: 40). Work by the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England) lead their chief investigator, Christopher Taylor to make the assertion, ‘…it is likely that moated gardens, of various forms, were a feature of upper middle class medieval life. This has an important bearing when we come to examine the evidence for early post-medieval gardens for there water filled enclosures were very common. It is possible that the tradition of a moated garden persisted long after moated sites themselves had become unfashionable’ (Taylor 1983:36).

As future accounts will show this practice continued throughout the sixteenth century and moats were important parts of the key water gardens of the early seventeenth century which are central to our study. We will argue that this indigenous tradition of garden making and the landscapes it inspired reflect an empirical craft based approach which in turn supports the scientific thinking of individuals such as Francis Bacon and later in the century those early scientists who inhabited Oxford in what Gouk termed a geography which played a part, ‘in the fostering of creativity and innovation in human systems at both social and cognitive levels’ (Gouk 1996: 257).

Bibliography

Aberg, A. F. 1978. Introduction in Aberg, A. F. (ed) Medieval Moated Sites, CBA Research Report No. 17. London: Council for British Archaeology

Creighton, O.H. 2002. Castles and Landscapes. London: Continuum Publishing Group

Creighton, O.H. 2009. Designs Upon the Land – Elite Landscapes of the Middle Ages. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press

Demidowicz, G. 2013. The North Court Prior to Leicester’s Works in Keay, A. and Watkins, J. The Elizabethan Garden at Kenilworth Castle. Swindon: English Heritage

Darnall, M.J. and Weil, M.S. 1984. The ‘Sacro Bosco’ at Bomarzo, Its 16th. century Literary and Antiquarian Context. Journal of Garden History Volume 4, issue 1

Deetz, J. 1991. Introduction: Archaeological Evidence of Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Encounters In Falk, L. (ed) Historical Archaeology in Global Perspective. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press

Farmer, S. 2013. Aristocratic Power and the “Natural” Landscape: The Garden Park at Hesdin, ca. 1291–1302. Speculum Volume 88, issue 3 pp 644 - 680

Giannetto, R.F. 2008. Medici Gardens – from Making to Design. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

Gouk, P. 1996. Performance Practice: Music, Medicine and Natural Philosophy in Interregnum Oxford. British Journal for the History of Science Volume 29, pp. 257 - 88

Halpern, L.C. 1982. The Use of Paintings in Garden History in Hunt, J.D. (ed) Garden History: Issues, Approaches, Methods. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks

Gleason, K.L. 1994. To Bound and Cultivate: An Introduction to the Archaeology of Gardens and Fields in Miller, N.F. and Gleason. K.L. (eds) The Archaeology of Garden and Field. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

Goodall, J. 2011. The English Castle. London: Yale University Press

Hall, M. and Silliman, S.W. (eds) 2006. Historical Archaeology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

Johnston, S. 2013. Graduate Archaeology at Oxford Conference, Keynote Address.

Lazzaro, C. 2005. Politicizing a National Garden Tradition: The Italianess of the Italian Garden in Lazzaro, C. and Crum, R.J. (eds) Donatello Amongst the Blackshirts: History and Modernity in the Visual Culture of Fascist Italy. New York: Ithaca Press

Le Patourel, H.E.J. 1978. The Excavation of Moated Sites in Aberg, A. F. (ed) Medieval Moated Sites, CBA Research Report No. 17. London: Council for British Archaeology

Liddiard, R. 2005. Castles in Context. Macclesfield: Windgather Press

Morgan, L. 2012. Cavity, Historical Interiors of the Body. Curtin University Symposium - Interior: A State of Becoming http://idea-edu.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/P68.pdf accessed 14.10.2015

Rabb, T.K and Brown, J. 1988. The Evidence of Art: Images and Meaning in History in Rotberg, R.I. and Rabb T.K. (eds) Art and History – Images and their Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Ribouillault, D. 2011. Towards an Archaeology of the Gaze: the Perception and Function of Garden Views in Italian Renaissance Villas in Beneš, M and Lee, M. G. (eds) Clio in the Italian Garden Twenty-First-Century Studies in Historical Methods and Theoretical Perspectives. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks

Salter, M. 1999. The Castles of Devon and Cornwall. Malvern: Folly Publications

Scheeler, J. 2007. The Garden at Bomarzo – a Renaissance Riddle. London: Francis Lincoln Limited

Sharp, L. 2015 ‘Evidence of absence is not absence of evidence’. Hesdin's Garden of Earthly Delights and Orsini's Sacro Bosco at Bomarzo : Automata, Sculpture and Hydrology . Foxground, New South Wales: Privately Printed

Strong, R. 1998. The Renaissance Garden in England. London: Thames and Hudson

Tarlow, S. and West, S. (eds) 1999. The Familiar Past – Archaeologies of Later Historical Britain. London: Routledge

Taylor, C. 1983. Garden Archaeology Aylesbury: Shire Publications

Thompson, M.W. 1982. Kenilworth Castle. London: English Heritage

Tronzo, W. 2014. Petrach’s Two Gardens – Landscape and the Image of Movement New York: Ithaca Press

Truitt, E. R. 2015. Medieval Robots - Mechanism, Magic, Nature and Art. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

Van Buren, A. H. 1986. Reality and Literary Romance in the Park at Hesdin in MacDougall, E.B. (ed.) Medieval Gardens Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks

Wickham, L. 2012. Gardens in History – a Political Perspective. Macclesfield: Windgather Press

In the seventeenth century Oxfordshire was home to three remarkable gardens: Wadham College, Hanwell Castle and Enstone, site of the Enstone Marvels. In the finished thesis it will be argued that these gardens, through the medium of the people associated with them, played a role in the development of a way of working and indeed thinking which was later characterized as the Scientific Revolution. However, to establish this as being the case, it is important to understand the place these sites occupy in the general history of gardens and specifically the ways in which technology was expressed in the design and functioning of gardens. Hitherto garden history has been the largely a product of the views of art historians who have given the study a very specific focus and in the process have under-emphasised some of the social, cultural and technical significance of gardens, a situation which can be partly remedied through archaeology.

One could give an account of popular misconceptions along these lines… Garden history is easy. The Romans had gardens and some got buried. In the middle ages the Romans were forgotten about and gardens were little square plots and all about courtly love and medicinal herbs. Then came the Renaissance and the Italians dug up the Romans and a few books and copied them and we copied the Italians… and then the French… and then the Dutch and everything was terribly formal until Capability Brown came along and made the world safe for future generations of film producers wishing to shoot Jane Austen movies. In fact the English parkland style was so self-evidently superior it took over the world. Oh and then there was someone called Gertrude something who did something grey with her borders.

Although this is a caricature it captures something of the way in which garden history has been profiled in countless guidebooks and other popular publications. Like all caricatures there is, of course, an element of truth buried within it but so much is based on errors of one kind or another that it is, at heart, fundamentally misleading.

Garden History and Archaeology

The history of gardens has been written primarily by art historians and this simple fact has had a profound effect on our understanding of how gardens have developed and their importance in a wider cultural and social setting. Research over the past 25 years has revealed how flawed that understanding can be. The common assumption was that if gardens are essentially works of art then there must be an artist or at least a designer behind them and that all gardens must equally have a programme based on a recognizable and understandable iconography. Landscape architect Rafaella Giannetto has written extensively on this and has pointed out that one of the key locations used by garden historians in proclaiming the birth of the Renaissance garden ideal and its literary antecedents, the Villa Medici at Fiesole, has been misread on both historical and archaeological grounds (Giannetto 2008). From an historical point of view the chronology is all wrong and she has established that the gardens were essentially complete several decades before their purported designer came on the scene. In fact she shows that most of the early gardens in her study were the product of those craftsmen charged with management of the estate whose work was drawn into later theoretical constructs. It is an important point that will link with future analysis of seventeenth-century technology in that her concept of the artisan designer chimes with some of the recent archaeological work done on early scientific instruments where it is clear that workmen were manufacturing sophisticated measuring devices up to half a century before their assumed ‘inventors’ first wrote about them (Johnston, S. 2013).

Her archaeological perspective has allowed her to demonstrate that a number of key features which have been designated as being Renaissance garden archetypes were not constructed until the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries (Fig. 2). She further notes that, ‘writings on the most popular of the Florentine gardens tend to reiterate information that is often taken for granted and accepted without reservation’ (Giannetto 2008:ix). In a more radical challenge Lazzaro argues twentieth-century views of Italian garden history are primarily a by-product of fascist ideologies (Lazzaro 2005). Gianetto’s more empirical approach to garden history has been championed by archaeologists in the United Kingdom and United States who have, as we shall see, reshaped our understanding of medieval gardens to a remarkable degree.

Fig. 2 the Medici Villa at Fiesole, view from south east. Some of the terraces and walkways have been shown to be later additions.

Many of the most trenchant criticisms of art history have been made by art historians themselves. Rabb and Brown comment on the difficulties implicit in the fascination for ‘hidden messages, in teasing out the complex implications of symbols, mental patterns and cultural structures’ yet underscore ‘the hope for the tangible and the concrete’ (Rabb and Brown 1988:2). The primacy of images in art history in general and the study of historic gardens in particular is perfectly understandable, why get mud on your boots when the whole scheme of things is displayed in this painting or that estate plan? The fact is that images in this context can be profoundly misleading for three reasons. Firstly they give a distorted view of the generality of gardens by shifting the collective gaze onto a particular group of elite gardens. The richer and more admired the patron the more likely they would have been to have illustrations commissioned of their properties. Secondly such illustrations are then subject to the editorial control of both the patron and artist so that the portrayal may be flattering to the original and influenced by aesthetic principles so that particular features within the garden are relocated simply to make a better picture (Figs. 3 and 4). This in itself is not without significance as Halpern says, ‘They [ the images ] tell us what mattered to the villa owners, and in many respects they are most interesting in their contradiction of reality’ (Halpern 1992: 183), Ribouillault amplifies the point, ‘images of gardens which were previously considered to be “documents” are now starting to be studied as “monuments” ‘( Ribouillault 2011: 204). Any account which builds elaborate theories about space, time and perspective on images of gardens alone must be suspect. Finally further complications arise when illustrations of planned proposals are treated as if the features were actually built which was quite frequently not the case (Currie 2005:27).

It is obvious that garden history would not exist without art history and much of what has been written over the past century constitutes an essential part of the study of gardens but many gardens, actually most gardens, lack the kind of source materials that makes them accessible to this kind of investigation and so the particular contribution that archaeology can make comes to the fore. The criticism has been made in the past that the use of archaeology to study the historic past is ‘the most expensive way in the world to know something we already know’ (Deetz 1991:1) but then archaeology goes on repeatedly to deliver the goods when it comes to new understanding of the recent and not so recent documented past (See for example Tarlow and West 1999 and Hall and Silliman 2006 ). It does this by drawing on a variety of techniques to expose the material remains of the past. In the context of gardens this includes survey, notably of earthworks, analysis of aerial photographs, geophysics and in some cases excavation. This data is then subject to what Gleason describes as, ‘The ever expanding variety of analytical techniques available to archaeologists to help reconstruct the spatial and perceptual environment people would have experienced in the built landscape’ (Gleason 1994: 3). Archaeologists may be deluding themselves to a certain extent in their claim to scientific objectivity and only dealing with facts but there is no doubt that archaeological input can have the effect of nailing theoreticians’ feet to the ground.

Fig. 3 Villa Medici at Castello, lunette by Giusto Utens from 1599 from the Villa Medici at Petraia, note the strongly symmetrical layout.

Fig. 4 Aerial view of Villa Medici at Castello from Google Earth showing the true asymmetric arrangement of villa and gardens

An extraordinary instance of the tendency to theorise in the absence of all the facts is the flood of scholarly articles that have followed the ‘rediscovery’ of the Sacro Bosco at Bomarzo, Italy in 1947 by the surrealist Salvador Dali and critic Mario Praz (Morgan, L. 2012). Remarkable by any standards this site might today be termed a sculpture park. Scattered around a fairly limited area are a number of huge figures carved out of natural boulders of the local peperino stone lining a narrow stream cut gorge. Constructed between 1550 and 1580 by retired soldier Vicino Orsini the garden has inspired almost as many interpretations as there are commentators. Literary inspiration is claimed for Colonna’s Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1499), Aristo’s Orlando Furioso (1532) or Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata (1581). (See summary in Darnall and Weil 1984). The futility of all this effort is captured by Cody, ‘the bosco’s ability to attract all manner of iconographic or programmatic readings while ultimately partaking of none, seemingly explains the near total lack of analytical or interpretive consensus within the last sixty years of scholarly inquiry (Cody 2013: 124). A particularly interesting proposal by Scheeler is that the slightly tipsy stance of a Pegasus poised unsteadily upon a token Mount Parnassus is that this reflects Orsini’s conviction that the full body of learning itself stood on uncertain ground (Scheeler 2007: 56). In fact a careful examination on the ground reveals that the whole stone basin supporting the fountain has cracked away from the bedrock and slumped to one side almost certainly as a result of an earth tremor (Fig.5). Sharp has gone even further proposing an entire programme of water powered automata installed as an aid to seduction (Sharp 2015). Archaeological examination of identified features showed them to be mainly lavatoio (washing places) or drinking troughs (Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 5 Bomarzo, The Pegasus Fountain view from west, the crack can be seen on the left hand side.

Fig.6 Bomarzo, lavatoio view from south east – not a housing for automata.

Medieval Gardens

In attempting a brief history of gardens we need to pay due attention to the basics, so until the advent of modern materials and technologies the ingredients available for garden making have been essentially the same: rock, earth, water and of course plants. The permutations within these ingredients are both limited and infinite so a hillside can be either sloping or stepped, few options, but within that limitation many different configurations are possible. Hence it is that something like terracing on its own as a stylistic trope is of limited use for what else are you going to do on a sloping site? In addition England with its preponderance of clayey soils and frequently more than ample supplies of water is a land where no gardener operating on a large scale can afford to be ignorant regarding the management of water. A further consideration may be that the best way to identify foreign influences, especially south European, is by picking out those elements which are clearly unsuited to the British climate; it rarely makes sense to soak your visitors to the skin over here but those kinds of giochi d’acqua (water games) are perfectly suited to a summer’s day in Italy. Archaeologists know that gardens don’t stand alone but must be considered within many contexts ranging from the geological to the political but as we have already noted, this has not always been the case.

It is troubling that in his admirable and comprehensive ‘The Civilization of Europe in the Renaissance’ Hale could note that, ‘It was not until the mid-fifteenth century that actual gardens began to be developed as amenities that deliberately expressed social and aesthetic ideas (Hale 1993: 520). Writing as recently as 2012 Louise Wickham could still maintain of the early Renaissance that enclosed medieval gardens, Hortus conclusus were ‘opened up by new ideas inspired by classical models’ and that ‘this was the first time that gardens had used borrowed scenery since Roman times’ (Wickham 2012: 62). Again, over reliance on images has warped our views of medieval gardens (Fig. 1), as Currie points out, the compressed perspectives of medieval illustration affected perceptions that medieval gardens uniformly consisted of small closely bounded spaces (Currie 2005: 9).

At the core of any study of medieval parks, gardens and managed landscapes lies the castle. There has been a really significant move away from regarding castles as military mechanisms to a much more nuanced appreciation of their role as administrative, social and cultural hubs which formed a back drop for economic, political and technological display, what Liddiard calls ‘courtly choreography’ (Liddiard 2005: 51). Goodall in his magisterial survey of English castles suggests that, ‘discoveries and research over the last twenty years… have reformulated the received understanding of the castle to the point of revolution’ (Goodall 2011: xvii) and this applies as much to the landscapes around them as to the buildings themselves. So, although a comprehensive history of medieval gardens in Britain has yet to be written, ample work has been dome on many individual sites and it is possible to begin a synthesis by examining some individual case studies. As we shall see there is much evidence for extensive and sophisticated developed landscapes in England from at least the twelfth century onwards. Indeed the Norman conquest is an appropriate place to begin; evidence for early Norman settlement is plentiful and the Gens Normannorum bought a degree of sophistication across western Europe from Ireland to Sicily. There are many instances of early Norman estates where the layout of castle, gardens and park clearly demonstrate the ability to use locations to make points about dominance and subjugation whilst at the same time creating a landscape that is productive and beautiful.

At Restormel in Cornwall the castle was established around 1100 by the Cardinham family (Salter 1999:32). Its location has many points of interest (Fig. 7). It is certainly not the most defensible spot in the area which actually lies to the south west and is occupied by the site of a Roman fort, nor is it close enough to offer protection to the town and bridge at Lostwithiel but it is intervisible with the town and the surrounding countryside which by the mid-thirteenth century had become a elaborate park under the control of the Earls of Cornwall. In his analysis of the landscape Creighton describes how, ‘the building was ‘keyed into’ a local setting that was manipulated, at least in part, with an eye for aesthetic value, thus amounting to a designed landscape’ (Creighton 2009: 17). Features included a mill and hermitage set on the banks of the Fowey below the castle and the careful alignment of the park boundary so it is, in effect, invisible from the castle creating the illusion of a much larger estate. Particularly noteworthy is the circular wall walk on the castle which seems designed for promenading and appreciating the view, it makes poor sense defensively. Now it may be argued that aspects of this are simply an over-interpretation of fortuitous juxtapositions within an entirely functional landscape but these ideas can be seen further developed at Kenilworth where the physical efforts to transform the landscape were enormous.

Fig. 7 The park at Restormel (after Creighton 2009). Inset aerial view of castle (Google Earth).

Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire was also begun in the twelfth century. From a study of contemporary charters Liddiard contends that the founder Geoffrey De Clinton defined a designed landscape of multiple components which formed the setting for four centuries of refinement (Liddiard 2005: 120). Examination of the castle’s plan as it stood prior to the famous siege of 1266 is instructive. A huge dam lay to the south of the main castle enclosure with further dams to the east which created an extensive mere that surrounded the castle on the south and west sides (Fig. 8). According to earlier accounts this defensive work was further protected by a massive crescentic earthwork known as the Brays (Thompson 1982: 25) and together formed one of the most sophisticated examples of military engineering seen in the country. In practice this huge investment makes little sense militarily as it could be simply ignored by mounting an attack on the weakly defended northern side of the castle. Further developments in the thirteenth century underlined the true nature of this complex as a grand ceremonial entrance to the castle with a staged unfolding of what was in effect a landscape of pleasure and beauty, when approaching from the south the view is blocked by the Brayz and only starts to unfold once one has passed through the first gate. In 1374 instructions were given to create an enclosed garden which may have been on the site of the Elizabethan garden created in the early 1570s (Demidowicz 2013: 33). This investment continued, in 1414 Henry V ordered the construction of a pleasaunce north east of the castle, a large rectangular moated site enclosing gardens and pavilions all approached by boat across the mere and into a dock.

Fig. 8 The Kenilworth landscape (Background image: English Heritage).

This idea of a separate enclosed garden or pleasance finds earlier expression in the feature later known as Rosamund’s Bower at the royal palace of Woodstock. This garden based on a water source known as Everswell lay around 300 metres to the west of the palace. The surviving remains are fragmentary (Fig. 9) but John Aubrey sketched the ruins in the seventeenth century enabling a tentative reconstruction to be imagined (Bond and Tiller 1997: 46). We have a walled garden with an entrance tower a series of interconnected rectangular pools and walk ways with seats and niches (Fig. 10). The particular significance of this site is its early date, the 1170s and the possible design links with the Sicilio-Norman tradition of palace and garden building. The fact that there were dynastic and cultural links at the time with both Sicily and Iberia is well established (James 1990: 54) and Colvin in his exhaustive History of the Kings Works refers specifically to the palace of La Zisa in Palermo (Colvin 1963: 1015). The Islamic garden works surviving in Spain are well known but the remains of a series of elite buildings originating with the Norman kings of Sicily are less familiar largely because they have been absorbed into the ramshackle suburbs of the city (Fig. 11).

Fig. 9 Blenheim Park, Rosamund’s Well, view from south.

Fig. 10 Twelfth-century enclosed garden and pools at Everswell based on annotated sketch by John Aubrey.

Fig. 11 La Zisa, Palermo, view from south showing foundations of pool and pavilion.

A further example of Islamic influence combined with local practices existed at Hesdin, today located in northern France. Here in the latter part of the thirteenth century was created one of the most elaborate and extensive parks of medieval Europe. Robert II Count of Artois, on his return from foreign parts, most notably Sicily, brought along with him cohorts of southern Europeans, including Italians, and commenced work on extending and improving the park attached to his castle and town of Hesdin (Now Vieil Hesdin). The scale of this undertaking was huge as was the time and expenditure devoted to the construction of assorted fountains, pavilions and entertaining automata (Farmer 2013) . Some of these were incorporated into the castle but others were scattered around the park, especially in a marshy valley to the north. The automata in particular have attracted much attention (For example Tronzo 2014: 101 – 10 and Truitt 2015: 122 – 37). They are significant because they represent the kind of feature normally associated with later Renaissance gardens in what is termed the Mannerist style and because there is general acceptance their origins lie in Arabic and Byzantine prototypes. There is less agreement on the exact means of transmission, but whether through written texts or personnel they illustrate a high level of planning and management in an era before, in some people’s view, garden history begins. In the case of the famous Marsh Pavilion we see a fusion of north European technology developed through the construction of timber bridges and water mills with more exotic mechanisms whereby the bridge to the pavilion was enlivened with nodding and waving monkeys clad in badger fur. As an aside it is worth noting that many of the debates about the functioning of the park have centred around its layout which was largely reconstructed from documentary evidence (Fig. 13 van Buren 1986: 128) on the ground some conclusions are demonstrably false, for example as relating to the actual location of the Marsh Pavilion (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12 Landscape analysis based on field work relating the position of the Marsh Pavilion.

Fig. 13 Reconstruction of he Park at Hesdin based on documentary evidence (van Buren 1986).

Throughout the middle ages we see examples of large and small scale undertakings whereby ground is cleared, terraced and planted for effect, enclosed gardens are built and extensive systems of waterworks are incorporated into a grand scheme of improvement and enhancement of the landscape. This is far removed from the established view of medieval gardens and demonstrates the fact that there was a well established and sophisticated tradition of garden and park construction well before the advent of the Tudors. The degree of continuity between medieval landscapes and Tudor gardens can be illustrated by examining the works at Raglan Castle, Gwent. Whittle writing in 1989 adopts the conventional explanation that the extensive gardens still visible as earthworks today are a phenomenon of the Renaissance, ‘made around the existing castle between 1550 and 1646 by the 3rd., 4th. and 5th. Earls of Worcester’ (Whittle 1989: 83). However, a building programme initiated in 1465 lead to the creation of two courts enclosed with towers and a curtain wall lined with accommodation blocks and the truly colossal ‘Yellow Tower of Gwent’, a free standing structure of some magnificence (Goodall 2011: 368). It is difficult to believe that works on a comparable scale would not have taken place within the associated park. Whittle states that, ‘there is some evidence that there were gardens of a utilitarian nature at Raglan in the fifteenth century. A “Fysshe Pole” is mentioned in an inquest in 1465 and an early fifteenth century manuscript states of Raglan “… about the palace there were orchards full of apple trees and plums, and figs and cherries and grapes, and French plums, and pears and nuts, and every fruit that is sweet and delicious” ‘ (Whittle 1989: 83). The assumption of simple utilitarianism is interesting and as we have seen largely debunked by more recent scholarship. Although there is no hard and fast dating evidence it seems likely that the great pool to the north of castle was a late medieval construction as was the terracing to the west of castle, an ideal location for the orchards described (Fig. 14). The long pool to the south west with two rectangular islands at its southern end also seems to owe more to medieval methods of construction that those of the seventeenth century. Much is made of the terracing between the castle and the valley below as being a typically Renaissance feature yet examination on the ground reveals that the earlier fabric of the building hanging, as it does, above a narrow gorge to the east could not have been built without the support of said terracing (Fig. 15). It’s perfectly possible that additional features such as stone steps, a balustrade and summer house were added post-1550 but the earth-moving had already been completed. The point at which Renaissance influences come roaring in is possibly under the direction of Edward Somerset, the 4th. earl who is believed to have commissioned a series of shell lined niches around the perimeter of moat surrounding the great tower (fig. 16). These formerly held statues of Roman emperors but like other features, a water parterre for example, were elaborations upon a landscape already fixed in the fifteenth century. General surveys of late medieval castles with significant continuation through the sixteenth century continually demonstrates the ‘bolt on’ nature of Renaissance additions.

Fig. 14 Raglan Castle environs earthwork details taken from 1976 OS 6 inches to the mile map.

Fig. 15 Raglan Castle, terracing below the north tower view from south west.

Fig. 16 Raglan Castle, the Emperors Walk view looking north.

In this brief examination of medieval landscapes we have concentrated on sites associated with the very highest echelons of medieval society and so fallen into one of the traps already identified as a weakness for garden historys in general. To open up a slightly broader perspective it is important to consider what evidence there is for gardens and landscapes associated with the lesser nobles and gentry. The moat is a significant feature which can be used to demonstrate continuity in approach to gardens oflesser status throughout the middle ages and into the early modern period. Archaeology provides much of the material for this and interest centres on that category of field monument known as the homestead moat. The familiar presence of moats around many castles extends to lesser constructions and many people are familiar with the way in which moats enclose domestic structures as at Baddesley Clinton, Warwickshire (Fig. 17) or Harvington Hall, Worcestershire. What is less well known is that huge numbers of moats exist, estimates suggest more than 5,000 survive (Aberg 1978: 3), simply as earthworks and free of any standing structures. They can be found in a broad swathe, largely across the midlands of England. Traditionally these were explained in terms of the kind of well known sites mentioned above as essentially former locations of medieval manors, granges or important farmsteads and excavation on the whole supported this assumption. However, archaeologists were puzzled by instances of multiple moats in close association and by the number of ‘empty’ moats that were excavated (Le Patourel 1978: 40). Work by the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England) lead their chief investigator, Christopher Taylor to make the assertion, ‘…it is likely that moated gardens, of various forms, were a feature of upper middle class medieval life. This has an important bearing when we come to examine the evidence for early post-medieval gardens for there water filled enclosures were very common. It is possible that the tradition of a moated garden persisted long after moated sites themselves had become unfashionable’ (Taylor 1983:36).

As future accounts will show this practice continued throughout the sixteenth century and moats were important parts of the key water gardens of the early seventeenth century which are central to our study. We will argue that this indigenous tradition of garden making and the landscapes it inspired reflect an empirical craft based approach which in turn supports the scientific thinking of individuals such as Francis Bacon and later in the century those early scientists who inhabited Oxford in what Gouk termed a geography which played a part, ‘in the fostering of creativity and innovation in human systems at both social and cognitive levels’ (Gouk 1996: 257).

Fig. 17 Baddesley Clinton view from north.

Bibliography

Aberg, A. F. 1978. Introduction in Aberg, A. F. (ed) Medieval Moated Sites, CBA Research Report No. 17. London: Council for British Archaeology

Creighton, O.H. 2002. Castles and Landscapes. London: Continuum Publishing Group

Creighton, O.H. 2009. Designs Upon the Land – Elite Landscapes of the Middle Ages. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press

Demidowicz, G. 2013. The North Court Prior to Leicester’s Works in Keay, A. and Watkins, J. The Elizabethan Garden at Kenilworth Castle. Swindon: English Heritage

Darnall, M.J. and Weil, M.S. 1984. The ‘Sacro Bosco’ at Bomarzo, Its 16th. century Literary and Antiquarian Context. Journal of Garden History Volume 4, issue 1

Deetz, J. 1991. Introduction: Archaeological Evidence of Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Encounters In Falk, L. (ed) Historical Archaeology in Global Perspective. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press

Farmer, S. 2013. Aristocratic Power and the “Natural” Landscape: The Garden Park at Hesdin, ca. 1291–1302. Speculum Volume 88, issue 3 pp 644 - 680

Giannetto, R.F. 2008. Medici Gardens – from Making to Design. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

Gouk, P. 1996. Performance Practice: Music, Medicine and Natural Philosophy in Interregnum Oxford. British Journal for the History of Science Volume 29, pp. 257 - 88

Halpern, L.C. 1982. The Use of Paintings in Garden History in Hunt, J.D. (ed) Garden History: Issues, Approaches, Methods. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks

Gleason, K.L. 1994. To Bound and Cultivate: An Introduction to the Archaeology of Gardens and Fields in Miller, N.F. and Gleason. K.L. (eds) The Archaeology of Garden and Field. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

Goodall, J. 2011. The English Castle. London: Yale University Press

Hall, M. and Silliman, S.W. (eds) 2006. Historical Archaeology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

Johnston, S. 2013. Graduate Archaeology at Oxford Conference, Keynote Address.

Lazzaro, C. 2005. Politicizing a National Garden Tradition: The Italianess of the Italian Garden in Lazzaro, C. and Crum, R.J. (eds) Donatello Amongst the Blackshirts: History and Modernity in the Visual Culture of Fascist Italy. New York: Ithaca Press

Le Patourel, H.E.J. 1978. The Excavation of Moated Sites in Aberg, A. F. (ed) Medieval Moated Sites, CBA Research Report No. 17. London: Council for British Archaeology

Liddiard, R. 2005. Castles in Context. Macclesfield: Windgather Press

Morgan, L. 2012. Cavity, Historical Interiors of the Body. Curtin University Symposium - Interior: A State of Becoming http://idea-edu.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/P68.pdf accessed 14.10.2015

Rabb, T.K and Brown, J. 1988. The Evidence of Art: Images and Meaning in History in Rotberg, R.I. and Rabb T.K. (eds) Art and History – Images and their Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Ribouillault, D. 2011. Towards an Archaeology of the Gaze: the Perception and Function of Garden Views in Italian Renaissance Villas in Beneš, M and Lee, M. G. (eds) Clio in the Italian Garden Twenty-First-Century Studies in Historical Methods and Theoretical Perspectives. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks

Salter, M. 1999. The Castles of Devon and Cornwall. Malvern: Folly Publications

Scheeler, J. 2007. The Garden at Bomarzo – a Renaissance Riddle. London: Francis Lincoln Limited

Sharp, L. 2015 ‘Evidence of absence is not absence of evidence’. Hesdin's Garden of Earthly Delights and Orsini's Sacro Bosco at Bomarzo : Automata, Sculpture and Hydrology . Foxground, New South Wales: Privately Printed

Strong, R. 1998. The Renaissance Garden in England. London: Thames and Hudson

Tarlow, S. and West, S. (eds) 1999. The Familiar Past – Archaeologies of Later Historical Britain. London: Routledge

Taylor, C. 1983. Garden Archaeology Aylesbury: Shire Publications

Thompson, M.W. 1982. Kenilworth Castle. London: English Heritage

Tronzo, W. 2014. Petrach’s Two Gardens – Landscape and the Image of Movement New York: Ithaca Press

Truitt, E. R. 2015. Medieval Robots - Mechanism, Magic, Nature and Art. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

Van Buren, A. H. 1986. Reality and Literary Romance in the Park at Hesdin in MacDougall, E.B. (ed.) Medieval Gardens Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks

Wickham, L. 2012. Gardens in History – a Political Perspective. Macclesfield: Windgather Press