The Hanwell Park Project

The Building and Re-building of Castles in the Early Modern Period and the Changing Cultural Identities of the Elite.

Back to Introduction and Contents

The Building and Re-building of Castles in the Early Modern Period and the Changing Cultural Identities of the Elite.

Back to Introduction and Contents

Fig. 1 Cowdray House, Great Hall and Porch in 1859

Introduction.

The ‘decline’ of the castle in the early modern period is a much debated phenomenon. Twentieth century studies produced accounts based on changing military technology and the social and political circumstances of the elite. Whilst acknowledging some fanciful elements in their construction earlier accounts maintained some sort of military role for castles in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. More recent studies have further downplayed the defensive properties of these sites and have focussed on issues of power and display to explain the continuing popularity of military forms into the sixteenth century and beyond. Whilst acknowledging this we will attempt to show that on-going concerns for personal and familial security in the early modern period meant a continuing interest in maintaining a ‘strong house’.

The English Civil War has a lot to answer not least for the way in which its aftermath coloured popular perceptions of castles and affected the paradigms used by twentieth century castellographers. Such was the scale of destruction wrought at the end of the conflict (Porter 1994) with the ‘ruined’ castle as the norm it is easy to see how, in popular imagination, castles as a class of monument are often regarded as failures. Almost by definition a castle in ruins has failed in its primary duty of keeping the enemy out. Small wonder then that the historiography of later castles has viewed this almost as a time of terminal illness and that M.W. Thompson should entitle his volume ‘The Decline of the Castle’ rather than the evolution or metamorphosis or even triumph of the castle. The difficulty that Thompson, and other twentieth century writers had was with their very narrow functionalist view of castles. Thompson writes about, ‘the final period of the castle’s history when function played less and less part and display or even fantasy ever more part in the minds of the builders’ (Thompson 1987: vii) as if display were not a function in its own right. The supremacy of the castle as military hardware was powerfully challenged in a series of works in the 1990’s with the analysis of Bodiam Castle and its surrounding landscape becoming something of a cause célèbre (Fig. 2). Despite a number of rear guard actions fought by traditionalists by 2005 Robert Liddiard was able to write, ‘rather than judging castles as military buildings the historiographical trend is now to see them as noble residences built in a military style (Liddiard 2005: xi ). These arguments were largely developed in the context of English castles built during the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries but Creighton has carried the debate back to the early medieval period (Creighton 2002) whilst Johnson has expressed similar convictions about the reuse and lingering popularity of military styled structures into the early modern period. In particular he argues for an understanding of these elite buildings which is much more complex and nuanced and firmly rooted in a sense of the psychological ‘otherness’ of those who used or were used by these structures. (Johnson 1999).

Fig. 2 Bodiam Castle, view from the south-east

In the discussion that follows we shall use some of Johnson’s categories to explore the continuing significance of employing military styling to structures which were focuses for conflicts of a non-military kind arising out of the changing cultural identities of the elite. Johnson describes in an earlier piece, albeit partially repudiated in his 1999 paper, how ‘aristocracy and upper gentry in 16th-century England manipulated symbolic structures relating to the feudal past to lend ideological support to the Tudor social order. ‘ (Johnson 1992: 45). The emphasis is on control and power but as often in such cases control and power are closely shadowed by insecurity and paranoia. Whilst acknowledging the importance of these symbolic architectural gestures we will concentrate on the implications of real or imagined threats and the physicality of the responses made.

Security and the Elite

We need, therefore, to consider the nature of the threats to both individual security and the well being of the household as experienced by Tudor elites. In traditional accounts the impact of new technology figures large, especially increasingly powerful artillery (O’Neill 1960) and the resulting evolution in defensive forms, notably the bastioned trace, normally regarded as having been developed in Italy (Hughes 1974: 77 ). However as military responsibilities shifted largely in the direction of a centralized state, security remained an important consideration for the elite. More recent accounts stress the, ‘emergence of institutions which effectively defined and enforced ownership rights’ (Anderson 1992) and it is in defence of these and the system supporting the nation’s great landowners that ‘military’ architecture continued to be practiced.

Clearly, for the Renaissance elite, threats came from a number of directions: from the unruly peasantry to over-bearing monarch (Figs. 3 and 4). If it were possible to quantify these risks and demonstrate that the response to threat as expressed through contemporary buildings is in proportion to the risk – actual or perceived - then we would have done something to rehabilitate the defensive credentials of some early modern ‘castles’ although not their military ones. We will sketch out some of the areas likely to cause concern to Tudor or Elizabethan magnates and indicate the nature of the physical responses

that were made.

|  |

| Fig. 3 Unruly peasantry, 16th. C woodcut | Fig. 4 Over-bearing monarch, Henry VIII from an engraving of 1646 |

Robbery

Where the ‘have nots’ rub shoulders with the ‘haves’ the illicit transfer of property down the social chain is a common phenomena. Cockburn in his preliminary analysis of crime in England in the late sixteenth century notes, “thefts involving an element of breaking… were running at about 25% of all crimes against property up to 1598. (Cockburn 1977). In Elizabethan England there was a strong connection between famine and theft. For example in Essex in the years 1592 – 4 the average number of prosecutions per year for theft were 78.6, as compared with 178.3 for the famine years of 1595 – 7 (Walter and Wrightson 1976: 24). Whilst these figures do not seem unduly high compared with modern crime rates they are illustrative of the tendency in societies under stress for threats to property to increase and there were plenty of stressful passages throughout the early modern period: from the religious upheavals of the reformation to the collapse of the wool trade. The elite households were often reservoirs of prosperity and as we shall see elements of military styled building helped prevent that wealth ‘leaking’ away.

Uprisings

Peasant uprisings were not particularly common occurrences, for example only 45 outbreaks of rioting were recorded between 1585 and 1660 (Walter and Wrightson 1976: 26) and they were rarely violent. Hindle describes a exception in a series of anti – enclosure riots known as the Midland Rising of 1607 which ended in pitched battle at Newton in Rockingham Forest on June 8th. During the course of this something like 1,000 levelers were driven off and around 50 dispatched on spot. Many others were rounded up and executed after the event. Although there are few instances of these ‘rebellions of the belly’ (Hindle 2003: 137) resulting in direct attacks on the grand houses, ‘It is abundantly clear that elites were very often terrified’ (Hindle 2003: 140), a terror prompted by, ‘the propertied classes’ fear of the collective disorder hunger might breed’ (Walter and Wrightson 1976: 26). The fact that few great houses were attacked does not diminish the significance of having a strong house, similarly, the dearth of medieval sieges does not completely negate the effort that went into building castles in the 12th. and 13th. centuries (Liddiard 2005: 72)

Disputes with peers

The narrative of demilitarization and pacification of early modern elites by the Tudor dynasty was followed by a shift in values so that, ‘by the early seventeenth century the martial and chivalric codes of a warrior caste were transmogrified into the civic and humanist ethos of a service nobility (Hindle 2003, 132) In short one was more likely to be hit by a writ than a sword. However, there were still disputes which were settled by resorting to arms. An instance is referred to in connection with Ightham Mote, Kent. Its new owner, Sir Richard Clements, reconstructed the house between 1521 and 1529 and in doing so retained many medieval defensive features. In 1534 he gathered together a large band of around 200 to settle a dispute over land presumably by intimidating his opponent if not resorting to open combat ( Starkey 1982 cited by Johnson 1992). Whatever the case this indicates a climate where it still made sense to surround your house with stout walls and a water filled moat.

Fig. 5 Ightham Mote, Kent, from south

High Crimes of State

Although much of the plotting and political maneuvering which took place during the period was within the immediate ambit of the court, there was still a sense that a powerful lord required a powerful seat. This could rebound; if the sovereign believed that the construction was too prestigious it could contribute to the downfall of its lord as in the classic case of Cardinal Wolsey who handed over the recently built moated and turreted Hampton Court to Henry VIII in 1525. (Osborne 1982: 32). Occasionally open rebellion broke out as in 1569 when Thomas Percy, Seventh earl of Northumberland garrisoned his castle at Warkworth so strongly that, ‘Sir John Forster, then Lord Warden of the Middle Marches, had great difficulty getting possession of it for Queen Elizabeth 1’ ( Honeyman and Blair 1990 ). This demonstrates that at least some members of the elite retained some military capability almost as insurance should it ever become necessary to rise against the monarch. In extremis a defended house could be viewed as a refuge against pursuing forces as was the case with Coughton Court in Warwickshire following the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 (fig.6).

Fig. 6 Coughton Court by A.F. Lydon c. 1880

The Material Response

In order to consider responses to these and other threats to security we will start by examining features which Johnson analyses as relating to, ‘an underlying symbolic structure articulating a set of ideas about the ‘feudal’ past’ (Johnson 1992: 47). Whilst recognizing the validity of these symbolic interpretations we will attempt to broaden the discussion to include the continuing need for potential castles and rebuilt castles to define and control a protected space. Johnson explores moats, crenellations, gatehouses and display as his starting points and we will retain this order before finishing with a look at aspects of planning.

Moats.

The role of water filled ditches and associated features round a variety of medieval and late medieval monuments has been seen as multivalent (Taylor 1978: 5 - 8). Whilst undoubtedly providing a fine reflective setting for a grand house moats in the early modern period continued to offer enhanced security against the possibility of anything from a sneak thief to a full blown military raid. Much has been made of ease with which the dam controlling the moat around Bodiam Castle could be breached (Coulson 1991: 7) but even if the moat were drained a considerable expanse of knee deep mud would continue to be a significant barrier to most incursions. The fact that moats were understood to be continuing to fulfill their protective function is borne out by one of Shakespeare’s most celebrated extended metaphors:

‘This precious stone set in the silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall

Or as a moat defensive to a house’

(Richard II Act 2 scene 1 46 – 48)

Crenellations.

Obtaining a licence to crenellate was in Coulson’s words, ‘almost the trademark of the medieval English arriviste’ ( Coulson 1982: 70), indeed in the instance of Sir John de Cobham’s 1381 award he was so pleased with his he recorded it on a copper plate on the outer gate of Cooling Castle, Kent (Fig. 7). His oversized and rather fanciful crenellations and machicolations have, as we shall see, been held up as an example of a military styled structure with sociological and possibly metaphysical significance but little practical use. In the same way crenellations on ecclesiastic precinct walls have been viewed as symbolic of the church’s secular power, however, at the same time they show, ‘how the lesser dangers of intrusion and mob violence were met by a graduated response’ (Coulson 1982: 69 ).

Fig. 7 Cooling Castle, anonymous print of 1823

Gatehouses.

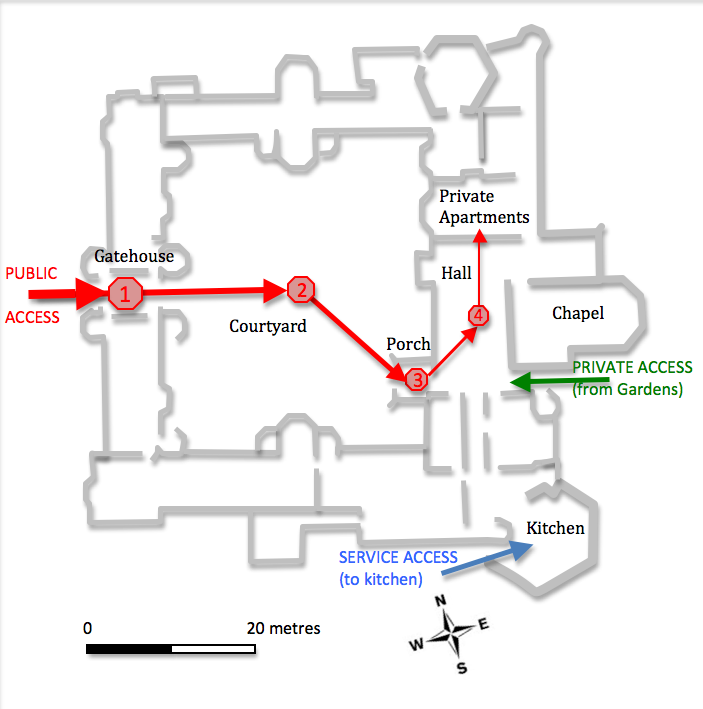

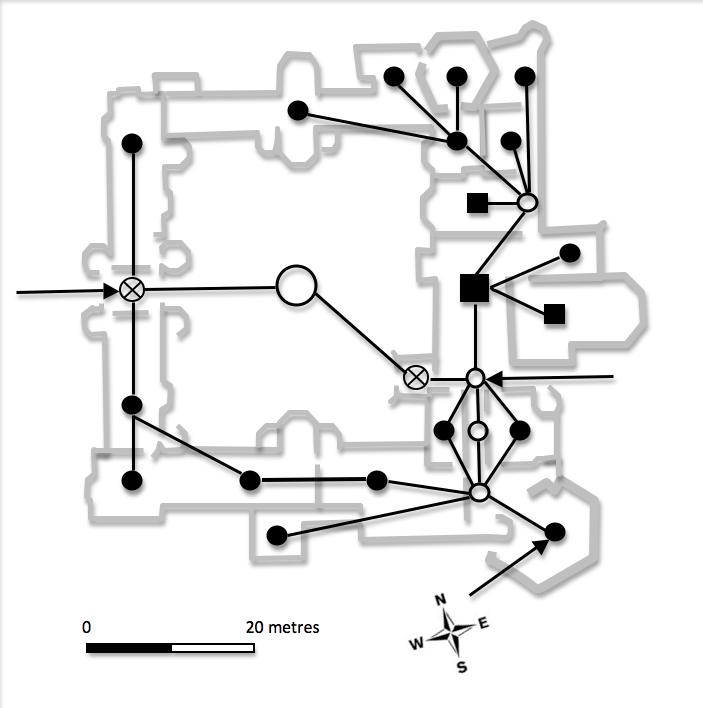

The analysis of the opportunities, frequently realized, that gatehouses offered for display has been well developed (for example Creighton 2002: 66). As a component of what Liddiard calls, ‘the martial front’ (Liddiard 2005: 127) the gatehouse not only loomed large in a monumental sense but frequently presented itself as a canvas on which family pretensions and loyalties could expressed through heraldic devices (Johnson 1992: 47). Indeed there seems to have been something of a cultural arms race in the Tudor period with gatehouses of increasing splendour running from Oxburgh Hall, Norfolk (1482) through the great gatehouse at Hampton Court (1521), the Holbein Gate at Whitehall (1532), Sir Richard Rich’s Leez Priory , Essex (1536 ), Titchfield Abbey, Hampshire (1538) to Nonsuch Palace, Surrey (1540). If this were an evolutionary process on might expect that the extraordinary eight storey extravaganza at Layer Marney, Essex would be the culmination of the sequence but in fact it was completed around 1523. Impressive though these structures were we must not loose sight of the fact that they were also gateways through which access could be controlled and when closed for the night, denied. Returning to Shakespeare the figure of the querulous gatekeeper in Macbeth must have been a familiar one. Comedic though his scene is it takes nothing away from the gatekeeper’s role in controlling entry to the castle. Johnson notes that during the Tudor period space became ‘increasingly segregated’ (Johnson 1992: 49) in which case the main gate is the first ‘filter’ on the flow of visitors which became progressively restrictive as the as the person of the elite was approached. (Fig. 8 a and b).

Fig. 8 a) Potential ‘check’ points as visitors approach private apartments. b) Access diagram showing tree-like structure indicating the degree of inaccessibility (West 1999: 108)

Although this is normally seen as a social ‘apartness’ it is reasonable to also view the process in terms of personal security. Johnson gives an account of the rebel visitation to Wressle Castle, East Yorkshire where a crowd approached the gates to demand that Percy, Earl of Northumberland, lead their uprising. The castle is described as, ‘a stage setting for a complex piece of political theatre’ (Johnson 1999: 72). This is certainly the case but Percy must also have felt much more comfortable about maintaining the diplomatic fiction of illness with a stout and no doubt heavily barred door between him and the mob (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9 Wressle Castl3 from the south-east

Display.

Commentators have responded in varying ways over the years to the spectacle of military ‘hardware’: merlons and crenels, drawbridges and portcullises, arrow loops and gun loops ‘bolted’ on to buildings of questionable defensive value. These responses have varied from Alan Sorrell’s comment on Herstmonceaux, Sussex, ‘a play castle built by a tired old soldier to remind him of battles of long ago’ (Sorrell 1973: 66) to Johnson’s remark about Warkworth Castle, Northumberland, ‘(it) is a piece of architectural symbolism as witty and as complex as anything from the Italian Renaissance’ ( Johnson 1999: 76). In most of these comments there seems to be a dichotomy between military value and decorative embellishments. Either a fortification is grim and dour and functional or else it is frivolous and stands solely as a testimony to its builder’s power or playfulness. In responding to Johnson’s plea for a more nuanced approach to these complexities it is worth pointing out that display has also always played a vital role in military operations from the elaborate elevated headwear sported by Napoleonic soldiers to the extraordinary cold war game of bluff and counterbluff played out in the Red Square May Day parades. To make oneself appear bigger, stronger, fiercer during the build up to conflict, or better the avoidance of conflict, is a strategy so fundamental as to be almost biologic. As Liddiard reminds us, ‘Building a residence in martial style could be an excellent way in which to display potential physical power’ (Liddiard 2005: 147) or equally to influence or intimidate potential attackers to the point where their combat efficiency is reduced.

Plan.

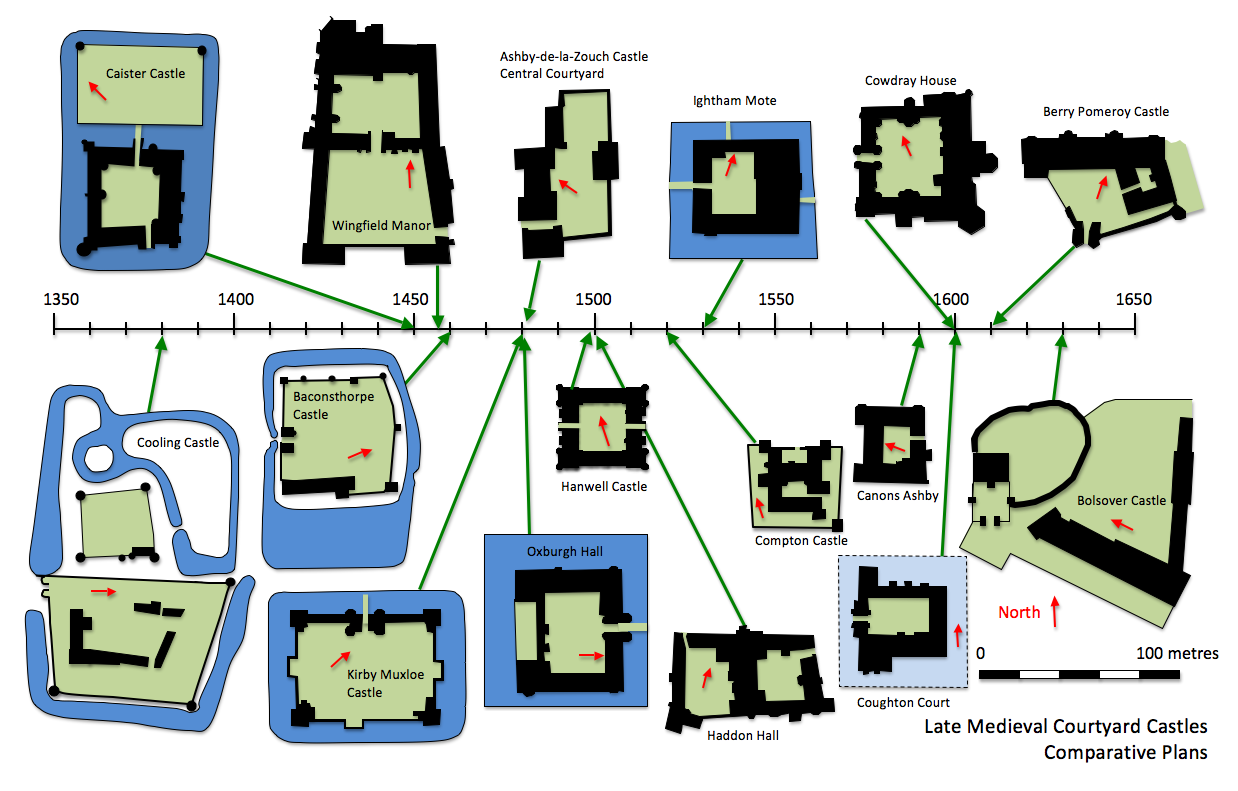

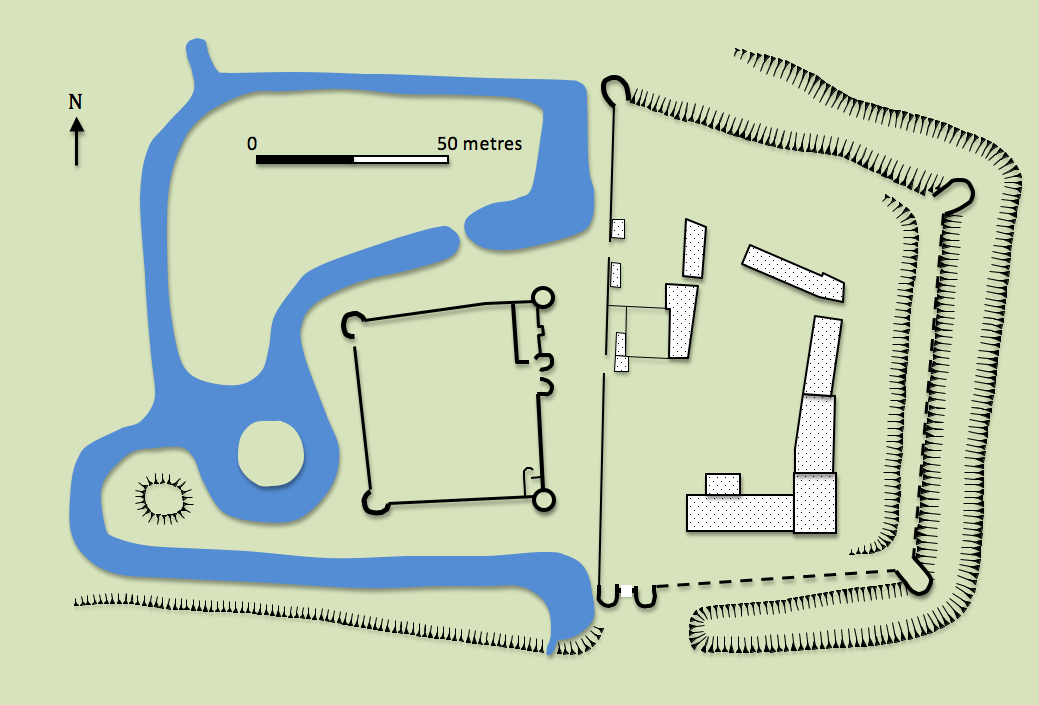

The courtyard house is a well recognised category of residence in the late medieval and early modern periods. (Thompson 1987: 43 – 70). Early examples can be described as having grown piecemeal with offices added on to a hall and solar block and then later accretions joining to embrace an enclosed area as at Penshurst Place, Kent (1341 – 1579) or Ashby-de-la-Zouch Castle, Leicestershire (1160 – 1483). Later constructions adopted the courtyard format from the outset as seen at Wingfield Manor, Derbyshire (1437 – 1455) or Cowdray House, Sussex (1520) Other buildings retained the concept of the defended enceinte but in a considerably weakened form as at Cooling Castle, Kent (1380) or Baconsthorpe, Norfolk (1460) (Fig. 10) Whatever the case there were clear benefits to be had from arranging accommodation around a central courtyard, benefits shared by late medieval colleges and hospitals. As well as conferring feelings of security and solidarity – what Johnson calls the expression of, ‘the notion of community’ (Johnson 1992: 49) the courtyard plan has many practical advantages relating to the control of resources and the management of risk. Casual incursions are prevented, visitors are monitored and controlled and strangers easily identified within the community of the courtyard.

Fig.10 Late Medieval courtyard Castles

Case Study.

In the supplementary notes to ‘The Historical Archaeology of England’ we read that, ‘Matthew Johnson uses Cooling as the first example in his 2002 book 'Behind the Castle Gate: Medieval to Renaissance' to critique the simplistic military interpretation of medieval castle architecture’ (HAE 2011). Indeed he does and in some respects Cooling seems an easy target with its exaggerated profiles and flimsy walls (Fig. 11). Most telling is its apparent vulnerability to a brief attack with the defenders capitulating after a few hours thus destroying any military credibility. A closer examination of the events of 1554 may give us pause for thought:

'Wyatt’s force, 2,000 strong, came before the castle at eleven o’clock A.M. and battered the great entrance of the outer ward with two great guns, while the other four were laid against another side of the castle. Lord Cobham defended his house with his three sons and a handful of men till five o’clock in the evening, having no weapons but four or five handguns; several of his men had then been killed, the ammunition was nearly expended, and the gates and drawbridge so injured that his men began to murmur and mutiny. So he was obliged to yield' (Mackenzie 1896: 11).

However unconvincing we may feel Cooling Castle is as a military structure it enabled Cobham to mount a sufficiently effective defence by a small household against a much larger attacking force. When he was later arrested by Elizabeth the simple fact of his stout resistance may have been enough to save his life.

Fig. 11 Cooling Castle, Kent

Conclusion.

Why did castles continue to be built or re-built in the early modern period? Well we have examined something of the importance of display and clearly symbolic meanings relating to a nostalgic view of past feudal glories or current statements of social or economic power were important. However, whilst recognising that the main tide of military advances had passed them by military styled buildings still offered significant degrees of protection to a variety of other threats to household security. The cultural identities of the elite had undergone a transformation into something more closely defined by reference to the emerging capitalist ethic based on the accumulation of private wealth which could be expressed through but also protected by what in purely military terms was an archaic structure – the towered and turreted castle.

Bibliography

Anderson, G.M. 1992. Cannons, castles, and capitalism: The invention of gunpowder and the rise of the west. Defence and Peace Economics 3. 2: 147 - 160

Cockburn, J.S. (ed) 1977. The Nature and Incidence of Crime in England 1559 – 1625 in Cockburn, J.S. (ed) Crime in England 1550 – 1800 , London: Methuen

Coulson, C. 1982. Hierarchism in Conventual Crenellation: An Essay in the Sociology and Metaphysics of Medieval Fortification. Medieval Archaeology 26: 69 - 100

Coulson, C. 1991. Bodiam Castle: Truth and Tradition. Fortress – the Castles and Fortifications Quarterly 10: 3 - 16

Creighton, O.H. 2002. Castles and Landscapes, London: Equinox Publishing

HAE 2011. The Historical Archaeology of England ( MA Course material, supplementary notes on ‘Blackboard’ ), Leicester: University of Leicester

Hindle, S. 2003. Crime and Popular Protest in Coward, B. (Ed) A Companion to Stuart Britain, Oxford: Blackwell

Honeyman, H.L. and Blair, H.H. 1990. Warkworth Castle and Hermitage, (Third Edition) London: English Heritage

Hughes, Q. 1974. Military Architecture. London: Hugh Evelyn

Johnson, M. 1992. Meanings of Polite Architecture in Sixteenth-Century England. Historical Archaeology, 26.3:45-56

Johnson, M. 1999. Reconstructing Castles and Refashioning identities in Renaissance England in, Tarlow, S. and West, S. (Ed) The Familiar Past, London: Routledge

Liddiard, R. 2005. Castles in Context, Macclesfield: Windgather Press

Mackenzie, Sir J.D. 1896. Castles of England, Their Story and Structure, New York: Macmillan

O’Neill. B. H. St. J. 1960. Castles and Cannon: A Study of early Artillery Fortifications in England, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Osborne, J. 1984. Hampton Court Palace, London: HMSO

Porter, S. 1994. Destruction in the English Civil War, Stroud: Alan Sutton Publishing

Salter, M. 2003. The Castles of England (Series) Malvern: Folly Publications

Taylor, C.C. 1978. Moated Sites: their definition, form and classification in Aberg, F.A. (Ed) CBA Research Report No. 17 Medieval Moated Sites, London: CBA

Thompson, M.V, 1987. The Decline of the Castle, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Walter, J. and Wrightson, K. 1976. Dearth and the Social Order in Early Modern England. Past and Present 71

West, S. 1999. Social Space and the English Country House in Tarlow, S. and West, S. (Ed) The Familiar Past, London: Routledge