Fig. 1 Work

starts on clearing the site

Introduction

This report has been produced as part of a large scale archaeological survey of Farnborough Park in Warwickshire (Wass 2011). During an examination of the area above the eighteenth- century cascade it became clear that at some point in the recent past an area of approximately 5 metres square had been cleared to reveal the damaged remains of a stone and pebble floor. Subsequently this had been covered with a layer of organic material primarily derived from the adjacent beech tree (Fig. 1). In the autumn of 2011 permission was obtained to clear this deposit in order that a detailed record be made of the floor and a small amount of extra excavation was permitted to determine the nature of the posts which supported a possible roof. On the basis of similar remains from period gardens we have identified the structure as a summerhouse or gazebo.

Topography

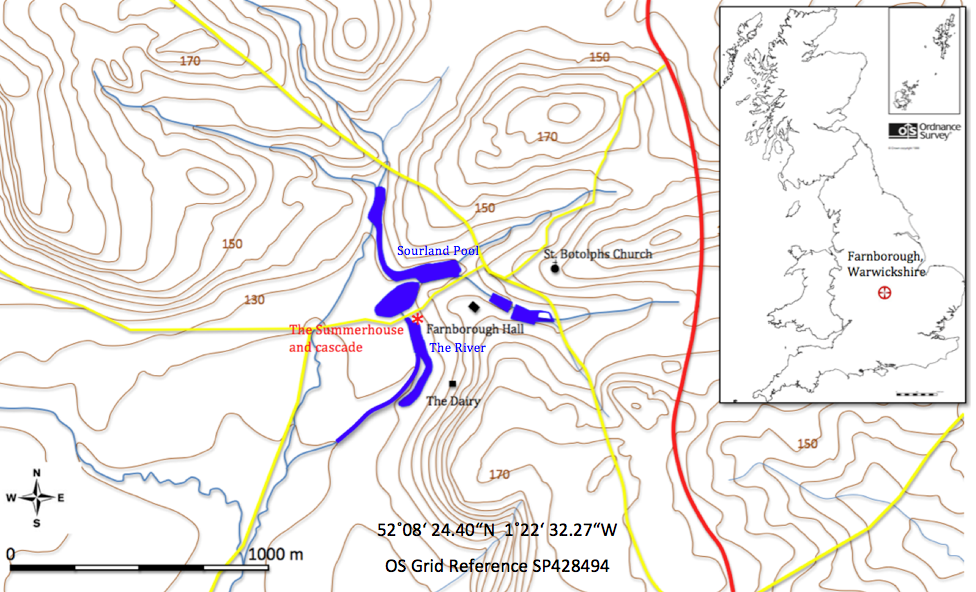

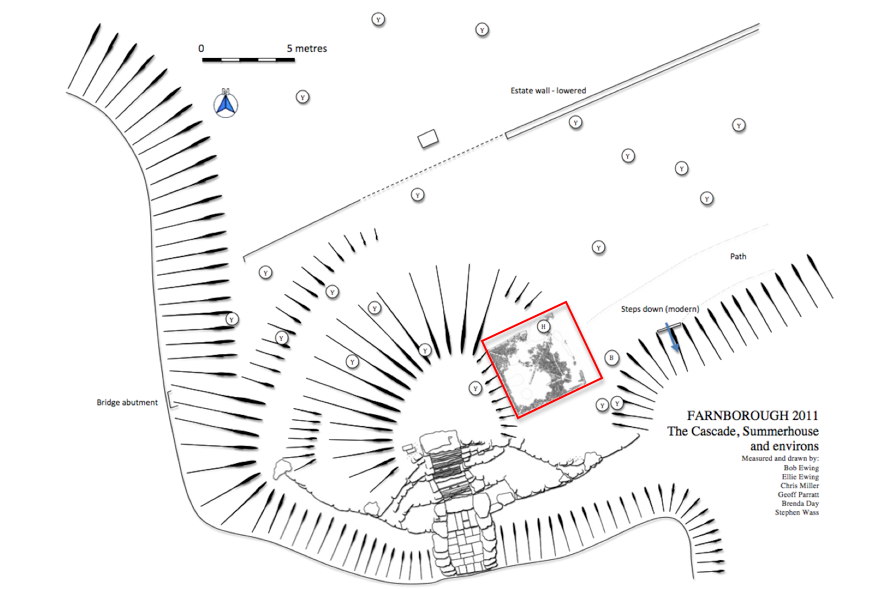

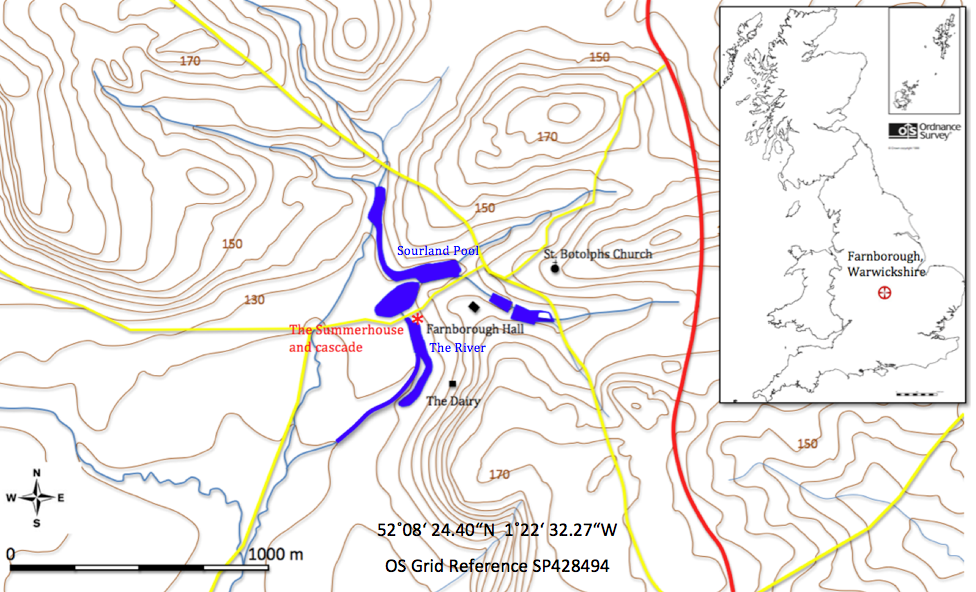

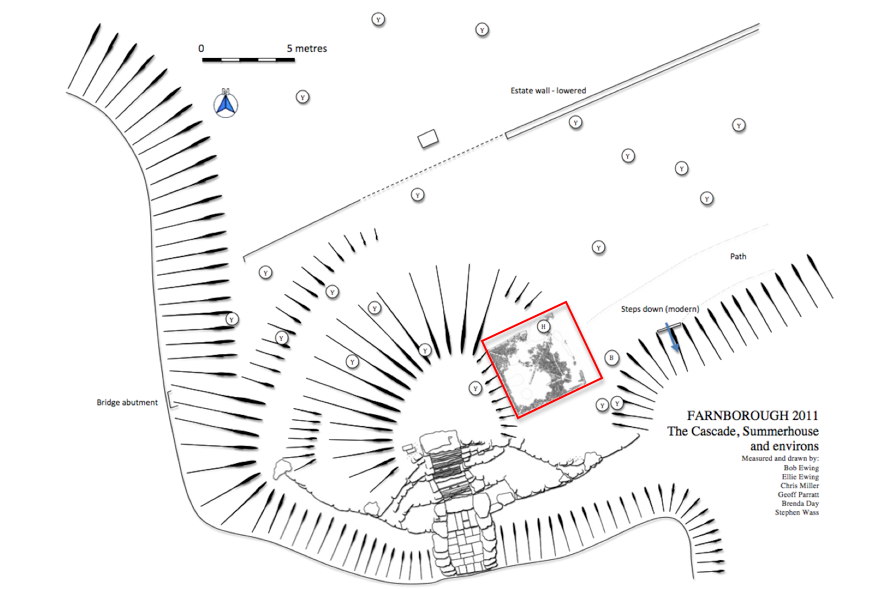

The position of the summerhouse can only be really understood in relation to the extensive landscaping that was carried out in the 1740s (Fig. 3) . Superimposed over medieval manorial earthworks and a Jacobean park was a remarkable landscape designed in the 1740s under the influence of Sanderson Miller (Meir 2006). This made use of a series of streams flowing down from the higher ground to the north and east. A cascade (Fig. 2) took water from Sourland Pool and emptied into the upper reaches of another body of water named the River. In order to achieve a suitably spectacular effect the Cascade was built up with a rough stone facing which was backed by a large mound of redeposited silty clay. The summerhouse is set into a terraced area cut into the north-east side of this mound (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3 Location map and local topography

Fig. 4 The Cascade, summerhouse and environs

Survey and Excavation

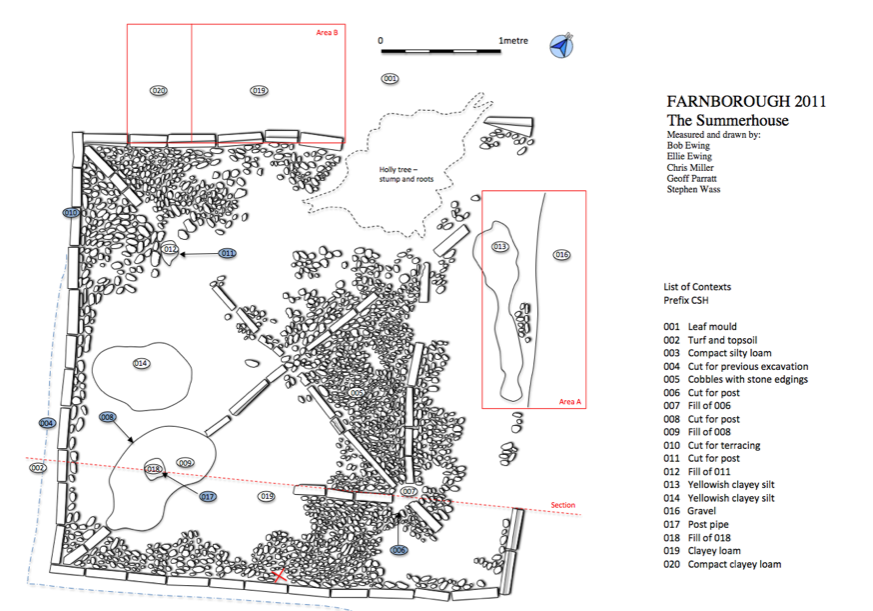

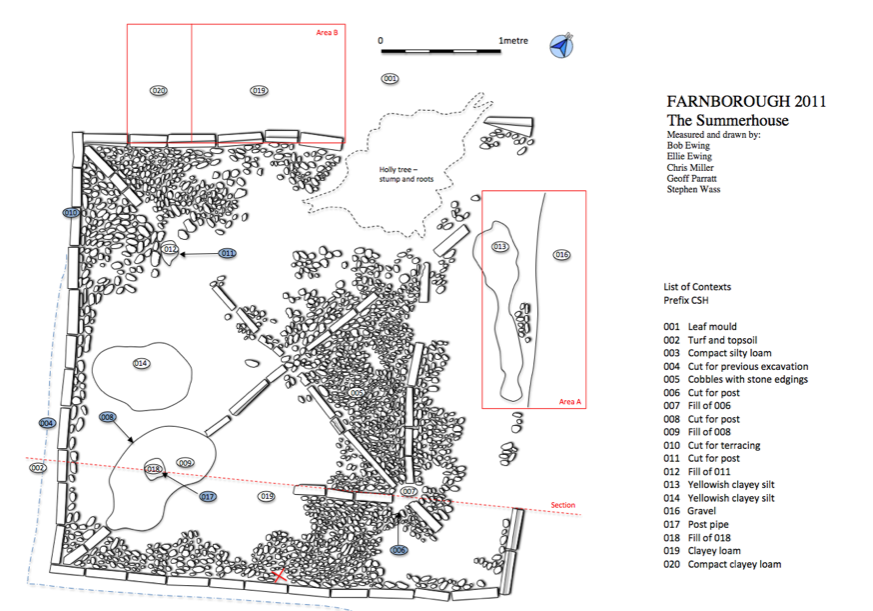

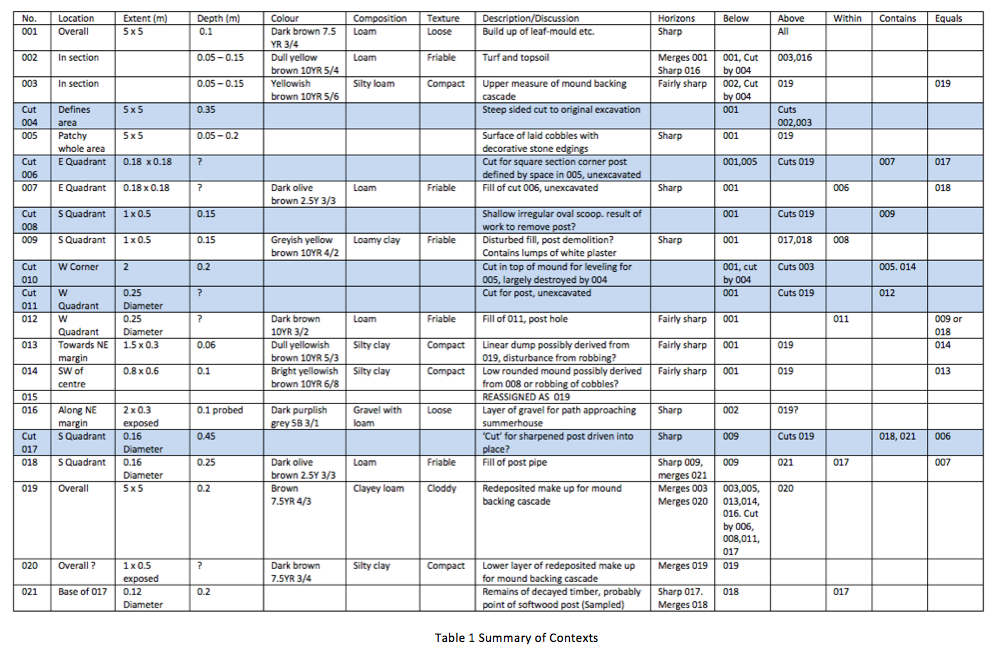

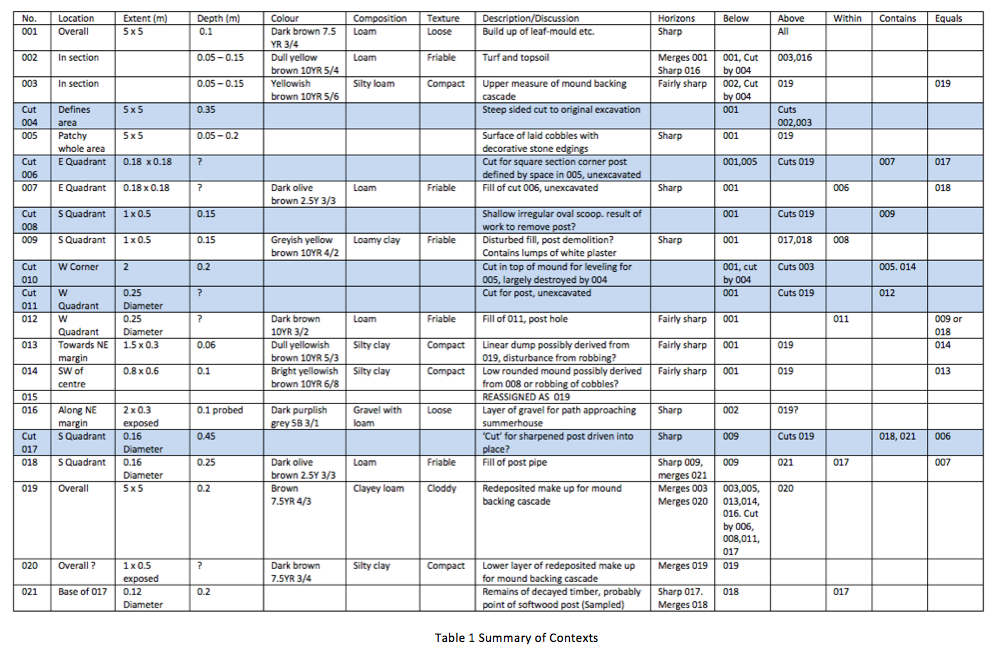

The immediate environs of the summerhouse were surveyed and detailed plans and elevations of the Cascade were drawn before work began to clear the site. This was done initially by brushing away the leaf mould and beech masts which had accumulated across most of the site (001). The exposed surfaces were then cleaned by gentle troweling to remove surface weathering (Fig. 5). At this point a plan was drawn (Fig. 6) and contexts assigned to the exposed features. Contexts were recorded on individual context sheets (Table 1).

The cut which defined the limit of the earlier excavation (004) was pronounced along to south and west sides of the area. Despite a degree of weathering there was no evidence that the cut had originally been vertical or trimmed so as to be drawn as a section. Revealed on the face of the cut was a layer or topsoil (002) and the upper portion of the make-up of the mound (003). There was no trace of the cut along the north and east margins of the site where a portion of the flooring may have remained visible as a surface feature. Once cleared the predominant feature of the site was the square floor surface of laid pebbles edged with stone strips (005). Although badly damaged by robbing and tree root intrusion, especially towards the northern corner where a large holly tree has taken root, enough remained to reconstruct the original layout. This consisted of two concentric squares, joined by diagonals which originate from the centre, laid out in stone edging. These stones were of variable length, between 0.2 m and 0.8 m and were set on edge and so had a fairly consistent height of around 0.1m.

Further

cleaning of the exposed surfaces defined two irregular low mounds of a

slightly yellower redeposited clay (013 and 014). As these were raised

above the level of the adjacent pebble surfaces these were interpreted

as dumps possibly derived from stone robbing .

Further

cleaning of the exposed surfaces defined two irregular low mounds of a

slightly yellower redeposited clay (013 and 014). As these were raised

above the level of the adjacent pebble surfaces these were interpreted

as dumps possibly derived from stone robbing .

Following the initial phase of clearance and recording the site was covered over with plastic sheeting and permission obtained to undertake some additional small scale excavation to clarify points that had arisen. This was done by identifying five separate areas for individual investigation (Fig. 6).

Area A

The site is approached via a path from the hall on its north-east side. We wanted to investigate the junction between the path and the entry to characterise the nature of the path and see if there were any special arrangements to mark the entry. Around 0.05 m to 0.08 m of topsoil (002) was removed from an area 2 m by 0.75 m to reveal an uneven surface of fine angular gravel (016). Some additional cobbling was also uncovered and it became clear that the path simply abutted the outer edge of the floor (Fig. 11). There was no evidence for a threshold or porch in the area.

Fig. 11 area A, to the right gravel surface, looking north-west

This report has been produced as part of a large scale archaeological survey of Farnborough Park in Warwickshire (Wass 2011). During an examination of the area above the eighteenth- century cascade it became clear that at some point in the recent past an area of approximately 5 metres square had been cleared to reveal the damaged remains of a stone and pebble floor. Subsequently this had been covered with a layer of organic material primarily derived from the adjacent beech tree (Fig. 1). In the autumn of 2011 permission was obtained to clear this deposit in order that a detailed record be made of the floor and a small amount of extra excavation was permitted to determine the nature of the posts which supported a possible roof. On the basis of similar remains from period gardens we have identified the structure as a summerhouse or gazebo.

Fig. 2 the

Cascade from the south-east

Topography

The position of the summerhouse can only be really understood in relation to the extensive landscaping that was carried out in the 1740s (Fig. 3) . Superimposed over medieval manorial earthworks and a Jacobean park was a remarkable landscape designed in the 1740s under the influence of Sanderson Miller (Meir 2006). This made use of a series of streams flowing down from the higher ground to the north and east. A cascade (Fig. 2) took water from Sourland Pool and emptied into the upper reaches of another body of water named the River. In order to achieve a suitably spectacular effect the Cascade was built up with a rough stone facing which was backed by a large mound of redeposited silty clay. The summerhouse is set into a terraced area cut into the north-east side of this mound (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3 Location map and local topography

Fig. 4 The Cascade, summerhouse and environs

Survey and Excavation

The immediate environs of the summerhouse were surveyed and detailed plans and elevations of the Cascade were drawn before work began to clear the site. This was done initially by brushing away the leaf mould and beech masts which had accumulated across most of the site (001). The exposed surfaces were then cleaned by gentle troweling to remove surface weathering (Fig. 5). At this point a plan was drawn (Fig. 6) and contexts assigned to the exposed features. Contexts were recorded on individual context sheets (Table 1).

The cut which defined the limit of the earlier excavation (004) was pronounced along to south and west sides of the area. Despite a degree of weathering there was no evidence that the cut had originally been vertical or trimmed so as to be drawn as a section. Revealed on the face of the cut was a layer or topsoil (002) and the upper portion of the make-up of the mound (003). There was no trace of the cut along the north and east margins of the site where a portion of the flooring may have remained visible as a surface feature. Once cleared the predominant feature of the site was the square floor surface of laid pebbles edged with stone strips (005). Although badly damaged by robbing and tree root intrusion, especially towards the northern corner where a large holly tree has taken root, enough remained to reconstruct the original layout. This consisted of two concentric squares, joined by diagonals which originate from the centre, laid out in stone edging. These stones were of variable length, between 0.2 m and 0.8 m and were set on edge and so had a fairly consistent height of around 0.1m.

Fig 5

Completion of initial clearance

Fig. 6 Site plan with list of contexts

Fig. 6 Site plan with list of contexts

The

width of those stones used to edge the squares was 0.08 m whilst the

stones lining the diagonals were noticeably thinner with a width of

around 0.05 m. The stones were smoothly finished and appear to be of

the kind of fine grained blue/grey ironstone found further to the north

and east into Northamptonshire. Roughly three quarters of these edging

stones remained in place. The edging stood slightly proud of the

surrounding cobbles and was shallowly buried in the layer

below

to a depth of around 0.05 m. This seems hardly adequate for the job and

a consequence is that many of the stones have been pushed

outwards (fig. 7). Where they had been disturbed or removed

there

was no sign of a cut being made into the layer below to receive them in

which case either the setting was dug to match very closely the width

of the edging stones or they were laid on a surface and a layer of

make-up was shovelled in around them.

The pebble surface consists of water rounded pebbles varying between 0.04 m and 0.12 m across and laid between the edging strips by the simple expedient of pressing them down into the make-up below. No attempt seems to have been made to create any kind of substrate for the pebble surface to be laid on but it is possible to see how the pebbles were laid in arcs presumably radiating out from wherever the labourer was crouching (Fig. 8)

Fig. 7 Edging strips along south east side looking south Fig. 8 View looking east showing laid patterns within pebble floor

The pebble surface consists of water rounded pebbles varying between 0.04 m and 0.12 m across and laid between the edging strips by the simple expedient of pressing them down into the make-up below. No attempt seems to have been made to create any kind of substrate for the pebble surface to be laid on but it is possible to see how the pebbles were laid in arcs presumably radiating out from wherever the labourer was crouching (Fig. 8)

Fig. 7 Edging strips along south east side looking south Fig. 8 View looking east showing laid patterns within pebble floor

The

points at which the diagonal stone edging intersected with the inner

square were of particular interest. The best preserved corner was the

eastern one (Fig. 9). Here both the edging strips and the pebble

surface respect what looks like the fill of a posthole

(006/007).

On the assumption that the laid surface would have approached the post

quite closely we can suggest a diameter of around 0.2 m for the post

and infer that it was round in section on the basis of the way in which

the edging strips are presented towards it.

Fig. 9 Site of eastern post looking south-west

Fig. 9 Site of eastern post looking south-west

The

southern corner which was by far the most badly robbed area revealed an

irregular oval area (009) which appeared to be filling a shallow scoop

(008). We associated this with the possible removal of another corner

post (Fig. 10). Similarly a smaller patch of fill (012) within a cut

(011) was also identified as the location of a third corner post.

Unfortunately the position of the west corner post was badly disturbed

by root growth and no particular cuts or fills could be

identified. There also appeared to be a central sunken

feature,

possibly another post hole. The effectiveness of the previous

excavation was attested to by the fact that we made no finds whilst

exposing these surfaces.

Fig. 10

disturbed area around site of southern post looking south-west

Following the initial phase of clearance and recording the site was covered over with plastic sheeting and permission obtained to undertake some additional small scale excavation to clarify points that had arisen. This was done by identifying five separate areas for individual investigation (Fig. 6).

Area A

The site is approached via a path from the hall on its north-east side. We wanted to investigate the junction between the path and the entry to characterise the nature of the path and see if there were any special arrangements to mark the entry. Around 0.05 m to 0.08 m of topsoil (002) was removed from an area 2 m by 0.75 m to reveal an uneven surface of fine angular gravel (016). Some additional cobbling was also uncovered and it became clear that the path simply abutted the outer edge of the floor (Fig. 11). There was no evidence for a threshold or porch in the area.

Fig. 11 area A, to the right gravel surface, looking north-west

Area B

We had no idea about the setting of the summer house, was it bordered by a path, a fence or planting? We hoped that evidence about this might be recoverable from the level ground immediately adjacent to the north-west. Below the leaf mould and topsoil (001/002) we cleared an area 2 m by 1 m down onto a broken surface of silty clay (019) which showed no evidence of any additional peripheral structures, however a number or irregular bowl like scoops may have indicated an element of former planting perhaps not dissimilar to the small shrubbery that lies adjacent to it today. In order to examine the character of the mound’s make-up (020) a 0.5 m wide strip was taken down a further 0.2 m (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12 Area B looking north-west after excavation.

Area C

The summerhouse seems to be on a terrace cut in to the rounded top of the mound into which the cascade is set. The original excavation appeared to have slightly overcut the trench’s edge so the relationship with the mound and any post-destruction deposition has been lost. However, there was a small area where it appeared that we might be able to recover something of the relationship between the earlier mound and the summerhouse. The edge of the cut (010) was examined but it became clear that the previous excavation had removed any post-demolition debris.

Area D

There seemed to be a central sunken feature into which at least three of the edging stones had sunk. We wanted to investigate this feature in order to determine if it represented some central feature such as a roof post or a setting for a table. Removal of a few loose cobbles and topsoil uncovered a slightly dished central area covered by cobbles but with no additional features (Fig. 13).

Area E

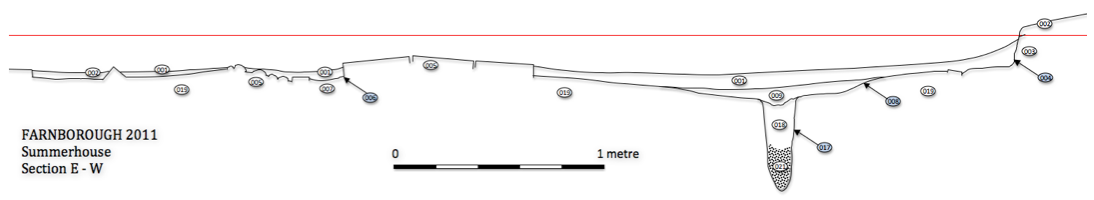

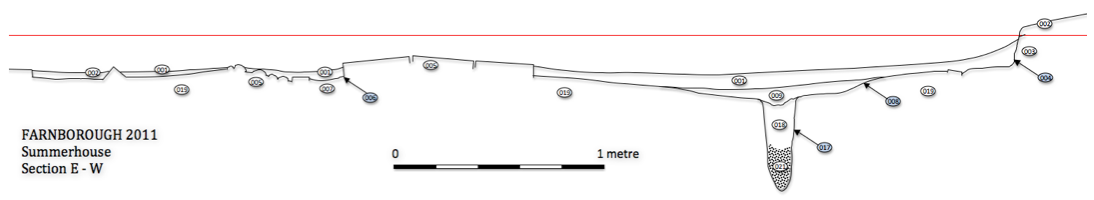

We had one surviving setting for the eastern corner post. The position of the presumed southern corner post was in an area from which the cobbling had been removed (Fig. 24) . Surface indications suggested the presence of a large post hole and discovering the whether the post was square or rounded in section and the depth to which it had been sunken would help us towards a better understanding of the complete structure. A broad shallow scoop roughly 1m by 0.5 m and up to 0.15 m deep was initially defined (008/009) and this was sectioned to determine the position of the post below it . The fill of the shallow scoop (009) sealed the post hole below (017/018) and was rather loose and disturbed producing quite large quantities (350 g) of white plaster fragments (Fig. 10). These were heavily degraded and unfortunately provided no evidence as to any surface treatment or finish. The remainder of the fill (009) was removed and the underlying post hole (017/018) completely excavated (Fig. 14 ). This was 0.16 m in diameter and 0.45 m deep and the lower 0.25 m was filled with the partially decayed remains (021) of the end of a sharpened wooden post (Fig. 15) . Samples were taken (FSH11/ 021/1) of this but initial examination suggested the posts were of softwood.

The site was covered with plastic sheeting over the winter of 2011-12 but now the work is complete thought needs to be given to its on-going preservation. Despite calls from a variety of members of the public who visited the dig last year we do not believe that the site is a candidate for reconstruction. A better plan would be to fell the decayed holly on the northern corner taking the trunk down to ground level and then cover the whole site in horticultural membrane and then bury it under an appropriate depth of bark chippings. The estate has the facilities to do this work once permission is given. A longer term concern is the condition of the cascade walling which supports the mound onto which the summerhouse is set. Portions of this walling are in a very fragile state and any collapse could also damage the mound (Fig. 23). The staff at Farnborough have done what they can to protect this structure but it needs some degree of expert advice and remedial work.

Stephen Wass 12.4.2012

We had no idea about the setting of the summer house, was it bordered by a path, a fence or planting? We hoped that evidence about this might be recoverable from the level ground immediately adjacent to the north-west. Below the leaf mould and topsoil (001/002) we cleared an area 2 m by 1 m down onto a broken surface of silty clay (019) which showed no evidence of any additional peripheral structures, however a number or irregular bowl like scoops may have indicated an element of former planting perhaps not dissimilar to the small shrubbery that lies adjacent to it today. In order to examine the character of the mound’s make-up (020) a 0.5 m wide strip was taken down a further 0.2 m (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12 Area B looking north-west after excavation.

Area C

The summerhouse seems to be on a terrace cut in to the rounded top of the mound into which the cascade is set. The original excavation appeared to have slightly overcut the trench’s edge so the relationship with the mound and any post-destruction deposition has been lost. However, there was a small area where it appeared that we might be able to recover something of the relationship between the earlier mound and the summerhouse. The edge of the cut (010) was examined but it became clear that the previous excavation had removed any post-demolition debris.

Area D

There seemed to be a central sunken feature into which at least three of the edging stones had sunk. We wanted to investigate this feature in order to determine if it represented some central feature such as a roof post or a setting for a table. Removal of a few loose cobbles and topsoil uncovered a slightly dished central area covered by cobbles but with no additional features (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13 Area

D after excavation

Area E

We had one surviving setting for the eastern corner post. The position of the presumed southern corner post was in an area from which the cobbling had been removed (Fig. 24) . Surface indications suggested the presence of a large post hole and discovering the whether the post was square or rounded in section and the depth to which it had been sunken would help us towards a better understanding of the complete structure. A broad shallow scoop roughly 1m by 0.5 m and up to 0.15 m deep was initially defined (008/009) and this was sectioned to determine the position of the post below it . The fill of the shallow scoop (009) sealed the post hole below (017/018) and was rather loose and disturbed producing quite large quantities (350 g) of white plaster fragments (Fig. 10). These were heavily degraded and unfortunately provided no evidence as to any surface treatment or finish. The remainder of the fill (009) was removed and the underlying post hole (017/018) completely excavated (Fig. 14 ). This was 0.16 m in diameter and 0.45 m deep and the lower 0.25 m was filled with the partially decayed remains (021) of the end of a sharpened wooden post (Fig. 15) . Samples were taken (FSH11/ 021/1) of this but initial examination suggested the posts were of softwood.

Fig. 14 Area

E after sectioning of shallow scoop and post hole, looking south-east

Fig. 15 Section drawing

Recommendations

Fig. 15 Section drawing

History

We have been unable to arrange access to any estate papers that may be held but map evidence indicates that the summer house was not present at the time of the survey for the 1772 estate map (Linnell 1772). However, it is shown on large scale Ordnance Survey maps from the 1880s. By 1923 it appears as a series of broken lines whilst by 1955 it is clearly no longer standing as a recognisable structure. Neither have we been able to confirm details of when or by whom the floor was originally excavated. Local informants have suggested dates between 1990 and 2000 and the late garden archaeologist Chris Currie has been named as a participant by at least one observer. It has also been suggested that much more in the way of cobbling was visible after the first clearance suggesting the possibility of some post-excavation robbing.

Fig. 16 Reconstruction, view from north

Analysis and Interpretation

Although not examined in great detail the earliest feature on the site was the large amount of make-up brought in to create the landscape feature known as the Cascade. The material, mixed silty loam, was clearly derived from local sources. Although we defined three separate elements to this (003, 019, 020) they were only really differentiated by the amount of disturbance by roots and penetration of humic material. We have no fixed date for the construction of this mound but the assumption has been made that this was part of the remodelling of the gardens in the 1740s. At some later point following the 1772 estate survey the summerhouse was erected towards the top of this mound on its eastern slope. This necessitated cutting into the slope (004) to create a level terrace on which to build.

It seems likely from examination of the post on the southern corner (017/018) that the four corner posts were driven into place and that the hard surfacing was laid up to them (Fig. 17). Whatever the case little preparatory work seems to have been done to provide a suitable base on which to lay the floor. Given the position of the posts at the corners of the inner square we have postulated a pyramidical roof which had deeply projecting eaves which provided cover to the outer portion of paving. Given the total lack of tile or slate fragments we further suggest that the roof was probably thatched or possibly, as in our reconstruction, covered with timber shingles (Fig. 16). Walling is not illustrated as we have no evidence for its inclusion although it of course perfectly possible that timber side panels could have been attached to the upright posts. Indeed it is possible that some such panels could have been plastered as per the plaster fragments found (009). Although there is no specific feature confirming its existence we have assumed some kind of central feature heavy enough to cause the pronounced local sinking there. This may have been a central table or perhaps a stand for a vase or a piece of sculpture.

Evidence for a phase of decay and demolition has been largely removed by the earlier excavation. Looking at the southern post (007,008) it seems likely that some effort was perhaps made to dig out the post before eventually snapping it off as the lower portion was clearly rotten. At the same time it is possible that some of the stone edging and pebbles were removed for use elsewhere in the garden. Indeed some informants have suggested that there were considerably more pebbles in place post-excavation than there are now which raises the alarming possibility that some robbing could have taken place quite recently.

As to dating we have a broad window as evidenced by maps for construction any time between 1772 and the 1880s. Considerable remodelling of the gardens was undertaken from 1815 under the direction of Henry Hakewell (English Heritage 2011) a period into which a rustic summerhouse or gazebo could fit quite nicely. A few historic examples have survived but again dating is problematic, however, they do illustrate some of the possibilities one should bear in mind when attempting a reconstruction such as shingles (fig. 18) or thatch (Fig.19) as roofing material, decorative ‘stick work’, (Figs. 20 and 21) and open sides (Fig.22). This image of a summerhouse at Blenheim may well be the closest parallel, despite its hexagonal plan (Fig. 23), for the appearance of the example at Farnborough.

The paucity of finds, despite the previous excavation, was a little surprising. When examining area B adjacent to the north west side of the structure we might have expected some traces of debris associated with the summerhouse’s previous use. There was nothing, perhaps indicating a short or very limited period of use or possibly the fact that the structure acted as an eye-catcher alone.

Fig. 22 Summerhouse at Blenheim Park, Oxfordshire, 1893. Photograph by Henry Taunt (Photo reference Oxon. HER HT5825)

We have been unable to arrange access to any estate papers that may be held but map evidence indicates that the summer house was not present at the time of the survey for the 1772 estate map (Linnell 1772). However, it is shown on large scale Ordnance Survey maps from the 1880s. By 1923 it appears as a series of broken lines whilst by 1955 it is clearly no longer standing as a recognisable structure. Neither have we been able to confirm details of when or by whom the floor was originally excavated. Local informants have suggested dates between 1990 and 2000 and the late garden archaeologist Chris Currie has been named as a participant by at least one observer. It has also been suggested that much more in the way of cobbling was visible after the first clearance suggesting the possibility of some post-excavation robbing.

Fig. 16 Reconstruction, view from north

Analysis and Interpretation

Although not examined in great detail the earliest feature on the site was the large amount of make-up brought in to create the landscape feature known as the Cascade. The material, mixed silty loam, was clearly derived from local sources. Although we defined three separate elements to this (003, 019, 020) they were only really differentiated by the amount of disturbance by roots and penetration of humic material. We have no fixed date for the construction of this mound but the assumption has been made that this was part of the remodelling of the gardens in the 1740s. At some later point following the 1772 estate survey the summerhouse was erected towards the top of this mound on its eastern slope. This necessitated cutting into the slope (004) to create a level terrace on which to build.

It seems likely from examination of the post on the southern corner (017/018) that the four corner posts were driven into place and that the hard surfacing was laid up to them (Fig. 17). Whatever the case little preparatory work seems to have been done to provide a suitable base on which to lay the floor. Given the position of the posts at the corners of the inner square we have postulated a pyramidical roof which had deeply projecting eaves which provided cover to the outer portion of paving. Given the total lack of tile or slate fragments we further suggest that the roof was probably thatched or possibly, as in our reconstruction, covered with timber shingles (Fig. 16). Walling is not illustrated as we have no evidence for its inclusion although it of course perfectly possible that timber side panels could have been attached to the upright posts. Indeed it is possible that some such panels could have been plastered as per the plaster fragments found (009). Although there is no specific feature confirming its existence we have assumed some kind of central feature heavy enough to cause the pronounced local sinking there. This may have been a central table or perhaps a stand for a vase or a piece of sculpture.

Fig. 17

Position of corner posts marked by ranging rods, view looking east

Evidence for a phase of decay and demolition has been largely removed by the earlier excavation. Looking at the southern post (007,008) it seems likely that some effort was perhaps made to dig out the post before eventually snapping it off as the lower portion was clearly rotten. At the same time it is possible that some of the stone edging and pebbles were removed for use elsewhere in the garden. Indeed some informants have suggested that there were considerably more pebbles in place post-excavation than there are now which raises the alarming possibility that some robbing could have taken place quite recently.

As to dating we have a broad window as evidenced by maps for construction any time between 1772 and the 1880s. Considerable remodelling of the gardens was undertaken from 1815 under the direction of Henry Hakewell (English Heritage 2011) a period into which a rustic summerhouse or gazebo could fit quite nicely. A few historic examples have survived but again dating is problematic, however, they do illustrate some of the possibilities one should bear in mind when attempting a reconstruction such as shingles (fig. 18) or thatch (Fig.19) as roofing material, decorative ‘stick work’, (Figs. 20 and 21) and open sides (Fig.22). This image of a summerhouse at Blenheim may well be the closest parallel, despite its hexagonal plan (Fig. 23), for the appearance of the example at Farnborough.

The paucity of finds, despite the previous excavation, was a little surprising. When examining area B adjacent to the north west side of the structure we might have expected some traces of debris associated with the summerhouse’s previous use. There was nothing, perhaps indicating a short or very limited period of use or possibly the fact that the structure acted as an eye-catcher alone.

Fig. 22 Summerhouse at Blenheim Park, Oxfordshire, 1893. Photograph by Henry Taunt (Photo reference Oxon. HER HT5825)

The site was covered with plastic sheeting over the winter of 2011-12 but now the work is complete thought needs to be given to its on-going preservation. Despite calls from a variety of members of the public who visited the dig last year we do not believe that the site is a candidate for reconstruction. A better plan would be to fell the decayed holly on the northern corner taking the trunk down to ground level and then cover the whole site in horticultural membrane and then bury it under an appropriate depth of bark chippings. The estate has the facilities to do this work once permission is given. A longer term concern is the condition of the cascade walling which supports the mound onto which the summerhouse is set. Portions of this walling are in a very fragile state and any collapse could also damage the mound (Fig. 23). The staff at Farnborough have done what they can to protect this structure but it needs some degree of expert advice and remedial work.

Stephen Wass 12.4.2012

Fig. 23 The

cascade and summerhouse site from the south.

Fig. 24 Work about to begin

on the southern

post hole looking south

Bibliography

English Heritage 2011. Farnborough Hall, Banbury, England, Record Id: 1304 Register of Parks and Gardens

http://www.parksandgardens.ac.uk/component/option,com_parksandgardens/task,site/id,1304/tab,history/Itemid,305/

accessed 14.12.2011

Linnell, E. 1772. Farnborough Estate Survey, Warwickshire County Records Office Ref. z 403 (u)

Meir, J. 2006. Sanderson Miller and his Landscapes, Chichester: Phillimore

Wass, S. 2011 The Farnborough Park Project http://www.polyolbion.org.uk/Farnborough/Project.html

Archive

At the completion of the project this will be deposited with the National Trust with copies of appropriate documents left with the Warwickshire CRO.

Acknowledgements

Richard White and his staff and volunteers at Farnborough

Chris Mitchell for photography

The Diggers: Peter Braybrook, Brenda Day, Bob Ewing, Ellie Ewing, Chris Miller, Geoff Parratt, Joseph Wass, Verna Wass.

English Heritage 2011. Farnborough Hall, Banbury, England, Record Id: 1304 Register of Parks and Gardens

http://www.parksandgardens.ac.uk/component/option,com_parksandgardens/task,site/id,1304/tab,history/Itemid,305/

accessed 14.12.2011

Linnell, E. 1772. Farnborough Estate Survey, Warwickshire County Records Office Ref. z 403 (u)

Meir, J. 2006. Sanderson Miller and his Landscapes, Chichester: Phillimore

Wass, S. 2011 The Farnborough Park Project http://www.polyolbion.org.uk/Farnborough/Project.html

Archive

At the completion of the project this will be deposited with the National Trust with copies of appropriate documents left with the Warwickshire CRO.

Acknowledgements

Richard White and his staff and volunteers at Farnborough

Chris Mitchell for photography

The Diggers: Peter Braybrook, Brenda Day, Bob Ewing, Ellie Ewing, Chris Miller, Geoff Parratt, Joseph Wass, Verna Wass.