Excavations in Church Oakal Field

Farnborough Park, Warwickshire

Contents

| 1. Summary | 2. Location | 3. Background |

| 6. Church Oakal B Site | ||

| 7. Church Oakal A Site | 8. Finds | |

| 11. Acknowledgments | 12. Bibliography |

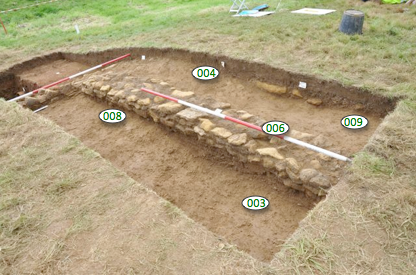

Fig. 1 The site, general view from south-west.

1.1 As part of a long term project to survey and

analyse the landscape associated with Farnborough Hall and its Georgian park

two trenches were opened in a field known as Church Oakal immediately to the

south of St Botolph's Church. An earthwork survey in 2011 had revealed the

presence of building platforms and a possible moated site and the excavations

were undertaken to investigate the character of the sites and their

archaeological potential.

1.2 Church Oakal B site was a

2 by 4 metre trench across the edge of a platform on the top of the hill

adjacent to the church yard. Work

uncovered a spread of destruction rubble with associated pottery from the first

half of the eighteenth century. The collapsed remains of the rubble core of a

large stone building, probably agricultural in nature, contained redeposited

early medieval pottery potentially associated with Saxon settlement close to

the church. A small portion of a metalled yard was uncovered to the east of the

wall.

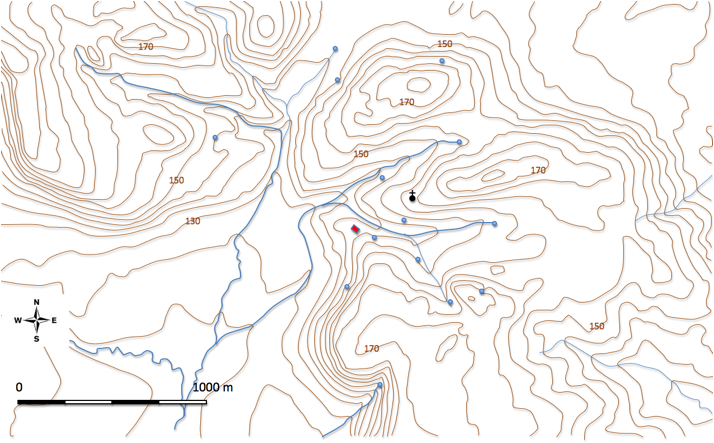

Fig.2 Topography and location map

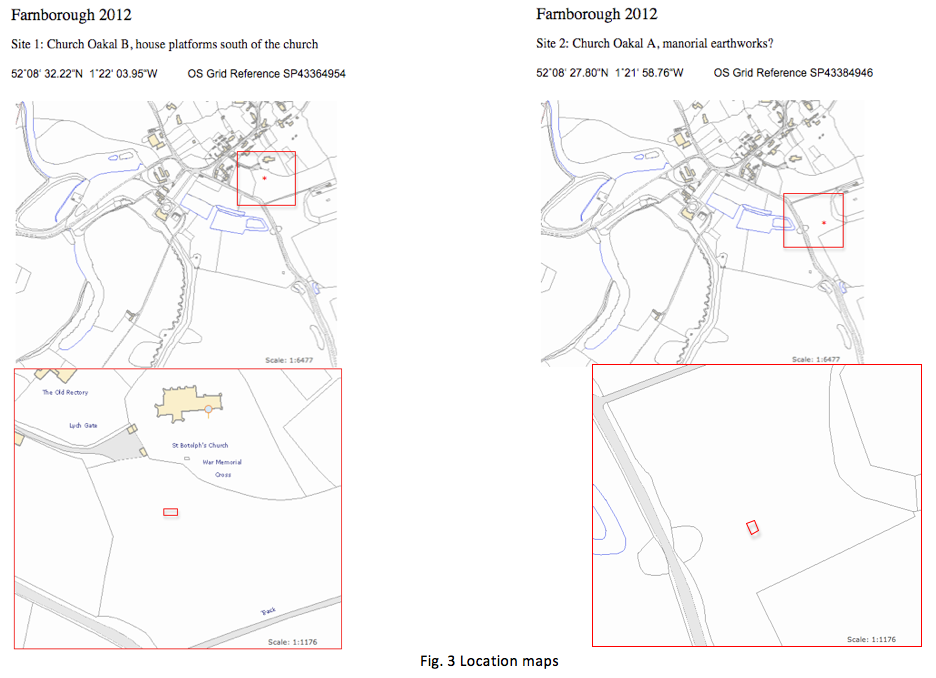

2.1 The sites investigated lie to the south of St.

Botolph's Church in the village of Farnborough in south Warwickshire, close to

the border with Oxfordshire and just over

9 kilometres north of Banbury (Fig. 3).

2.2 The

village lies on a northern outlier of the Cotswolds: a southern tilting mass

made up of early Jurassic marine shales, limestones and sands of the lias

group. The most prominent part of these deposits is a marlstone bed, which is a

calcareous, sandy ironstone and due to its relative hardness, forms an elevated

ridge (Williams 1975). Because of this the initial fall of the scarp is quite

steep with an overall height of around 40 metres. The rusty brown ironstone has been widely used locally for

building (Radley 2003: 209).

2.3 The scarp, running north-west to

south-east, is dissected by a number of streams which come together to the

south-west of the hall forming a re-entrant angle of low ground, sheltered by

heights to the north and east (Fig. 2).

The lower slopes consist of hill-wash and eroded material derived from the underlying

marlstone, whilst the flatter plain to the south-east is composed of alluvial

deposits of silt, clay and gravel, of periglacial origin. There are several

springs in the area, mainly clustered between the 145 and 160 metre contour.

Some of these exist as depressions in the face of the hill-side from which

water seeps, whilst others have been given some additional structure as at St.

BotolphÕs Well (Fig. 2).

2.4 As both sites were in unimproved pasture it was

necessary to obtain a derogation from Natural England to cover the disturbance

and re-instatement of the turf (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Church Oakal Field looking north

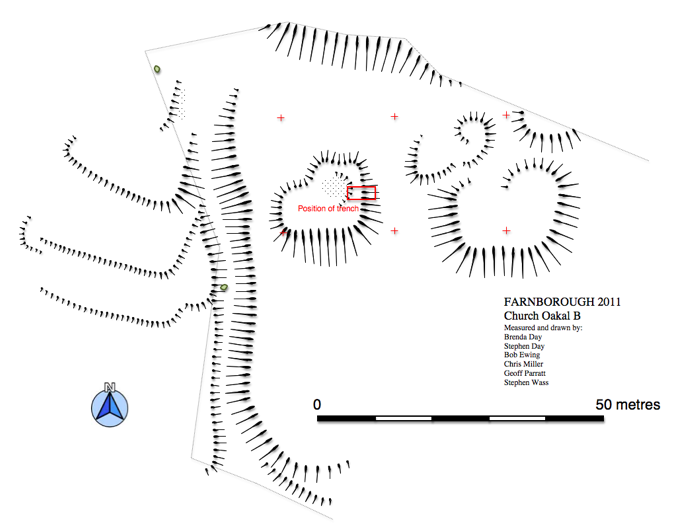

3.2 A detailed survey of the earthworks was carried

out in the spring of 2011. Church

Oakal lies to the south of St. Botolph's Church and to the east of the current

hall and park being separated from them by the Banbury road. The shape of the

field in the eighteenth century was rectangular, aligned east - west and

roughly 400 yards (370 metres) by 180 yards (160 metres). There was a narrow

projection to the south which overall created an 'L' shaped plan.

Topographically the field occupies the north side and bottom of a shallow

valley which lies between two hills; Oakal Hill to the south and Church Hill to the north (Fig. 5). The

water discharges to the west currently through a stone lined drain which passes

below the foot way which runs underneath the Banbury road by means of a well

made ironstone tunnel/bridge. Some of the field today is occupied by the

remains of the early nineteenth-century walled kitchen garden. Most of the

earthworks are along the western margin of the field and can be clearly seen

from the road, in addition there is access to the land via a footpaths which

run close to or through the sites.

3.3 Church Oakal B Site.

From the outset the empty field adjacent to the hilltop church seemed anomalous and so it was not surprising to find a series of well defined platforms indicating the presence of buildings (Fig. 6). Four distinct platforms exist which were tentatively identified as a farmstead with the main house on the crest of the hill on the western side of the complex, a larger building, possibly a barn to the east and smaller ancillary buildings to the north. This area is bounded on the north by the wall of the churchyard which acts as a revetment to the higher ground around the church. The wall appears to cut at least one platform. To the west of the platform complex is a clearly defined holloway which runs down the hillside from a point to the east of the church to the Banbury road where if curves round to match the existing roadway. On the other side of the park wall is St. Botolph's Well and it seems likely that the route linked the church to the holy well and perhaps additionally this part of the settlement to the road to Banbury. East of the holloway in a separate paddock are three low terraces with broad leveled tops and steep, low, well defined slopes. These are probably garden terraces and may relate to a later phase of occupation on the site. The middle terrace has earthwork traces of a possible set of steps or a ramp connecting it with the lower terrace. These earthworks could be associated with Mount Farm to the east or the rectory to the north.

3.4 Church Oakal A Site

3.5 Church Oakal C Site

The outline of the field in the 1772 estate map included this projection to the south. This boundary is still respected today although the fencing is modern. The irregular nature of these earthworks suggests quarrying and it may well be that the land was set aside from the adjacent arable either because of its continuing use as a quarry or perhaps more likely because of the difficulty of cultivating such broken ground. However, detailed survey of the remains indicates a degree of regularity to some parts of the site which may indicate other occupation (Fig. 5).

4.1 The

general objectives were as set out in the document, Further Investigations

around Farnborough Park, Warwickshire

Further specific objectives were:

From surface indications earthworks had been

interpreted as house platforms. There was a need to confirm the domestic and/or

agricultural character of the site and in particular identify the point at

which the buildings were demolished. Possibilities ranged from medieval

abandonment to clearance at the time of early seventeenth-century enclosure or

removal as part of the eighteenth-century landscaping process. Whatever the

case work here was intended to clarify this important point in the development

of both the village and the park.

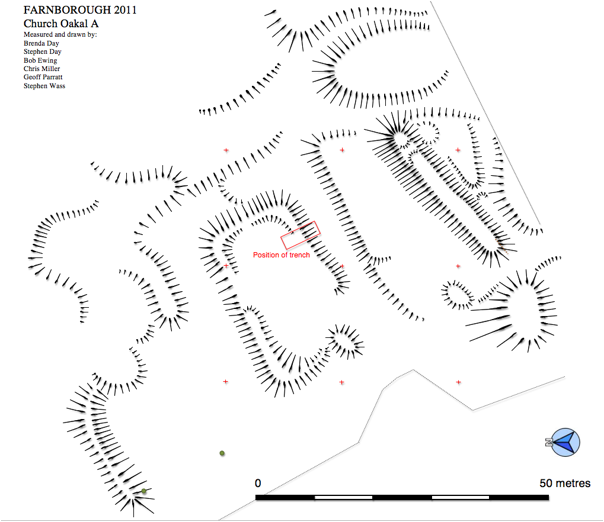

4.3 Church Oakal A site

Earthworks here were originally interpreted as a

moated site with associated fishpond and channels possibly linked to the

earlier medieval manor. However, further examination and reflection suggested

an alternate explanation: the earthworks could have represented garden features

associated with the Jacobean hall. Excavation was intended to determine which

of these possibilities was the most likely and recover some dating material.

5.1

Work was undertaken in line with procedures set out in ,

5.2 On both sites all work was undertaken by hand.

The turf was removed and stacked on plastic sheeting alongside the remaining

topsoil as it was removed. The upper surface of the rubble spreads uncovered in

each trench were recorded and then the destruction material carefully removed

until structural elements became clear. In some cases due to the depth of

destruction layers and recent material used for leveling one metre square test pits were

excavated down through this material to a depth of around 50 centimetres in

order to identify further archaeologically significant layers. A metal detector

was used both on site and on the spoil heaps to identify metal based small finds. In both cases the trenches were open

for less than a week and were back-filled and the turf re-instated within three

days. The drains which were removed from COA for photography were carefully

re-instated.

5.3 There were no deposits deemed suitable for

environmental sampling.

5.4 Degrees of confidence. Both excavations were

carried out under optimum conditions, fine, sunny and largely dry. Only one

really wet day was experienced and work able to continue under a temporary

cover. Whilst the two supervisors were widely experienced the other four

diggers, whilst very able student volunteers, worked under close supervision.

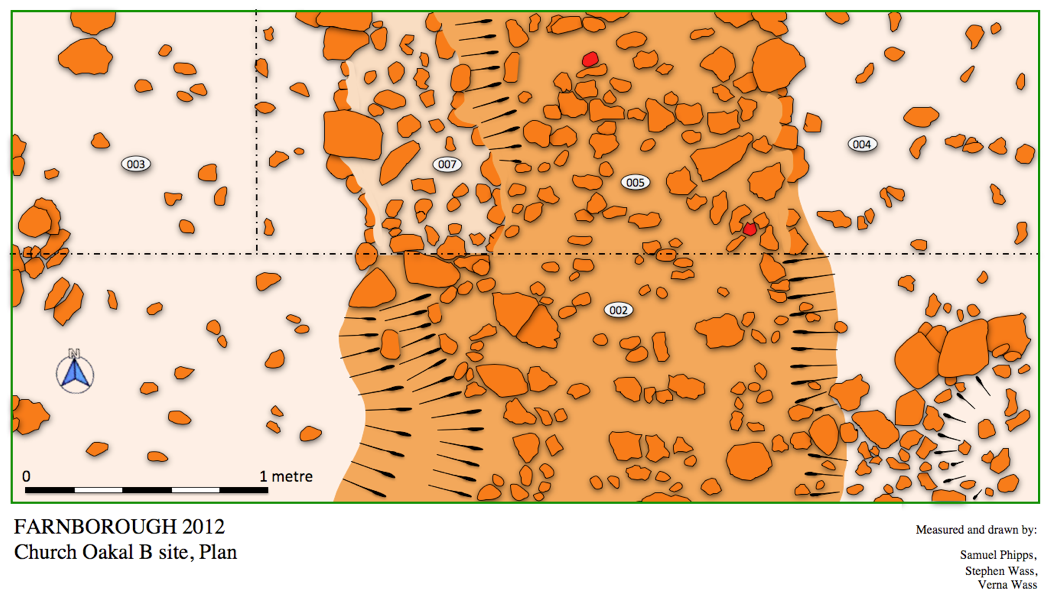

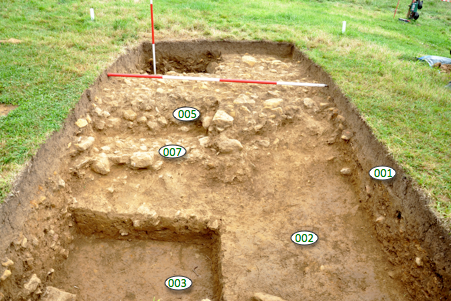

6.1 Results

The surface profile showed a distinct ridge running north to south across the centre of the area for excavation. Removal of turf and topsoil (001) revealed an overall spread of ironstone rubble set in a matrix of friable reddish brown loamy clay (002) which also had a pronounced central ridge which was interpreted as the core of a collapsed or partially robbed wall. Removal of 002 clarified this situation and a more densely packed area of larger pieces of ironstone rubble in a matrix of reddish brown silty loam (005) was identified as the wall's core. Further removal of 002 was organised so as to leave the south-east quadrant untouched as there seemed to be evidence of some additional structure in this area, specifically what appeared to be a setting of larger stones (010) marking out a quarter circle round a slightly sunken area (Fig. 8).

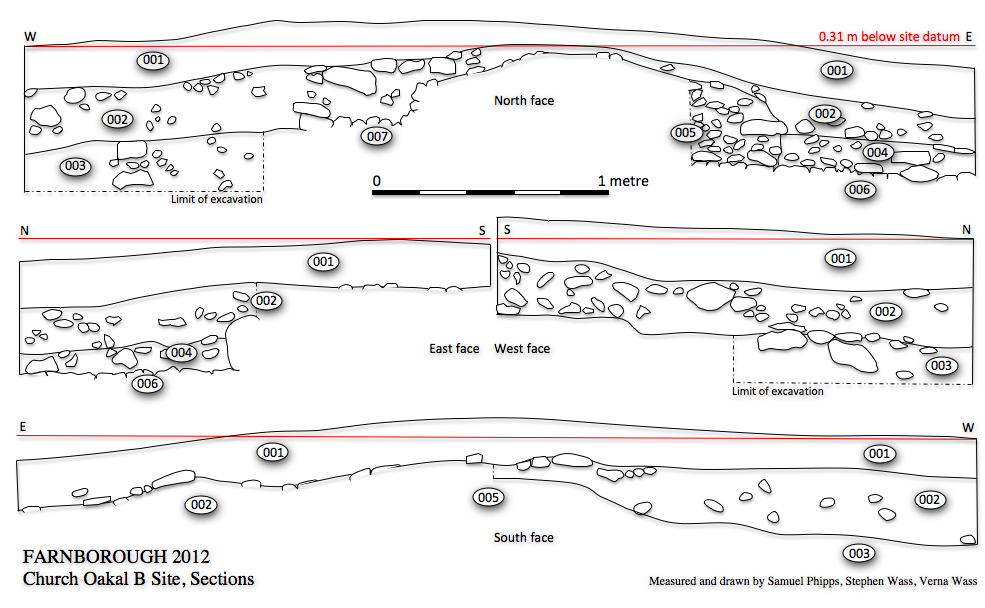

Fig. 110 Church Oakal B Site, sections

6.2 In other parts of the site 002 proved to be a

deposit of up to 40 cm in depth which contained large quantities of rubble

together with broken pieces of faced stones, several bent iron nails (Fig.21) and

pottery from the first half of the eighteenth century together with four pieces

of clay pipe stem. To the east of the wall only the northern half of 002 was

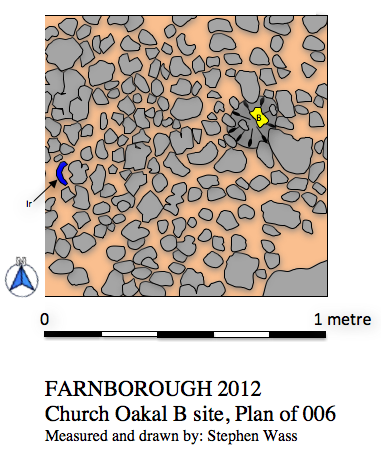

excavated down to a well laid metalled surface consisting of packed pieces of

the harder grey form of local ironstone (006). In order to determine the

relationship between this metalled surface and the wall a portion of the core

005 was removed indicating that at this point at least the wall was built on top

of the metalling. Some early

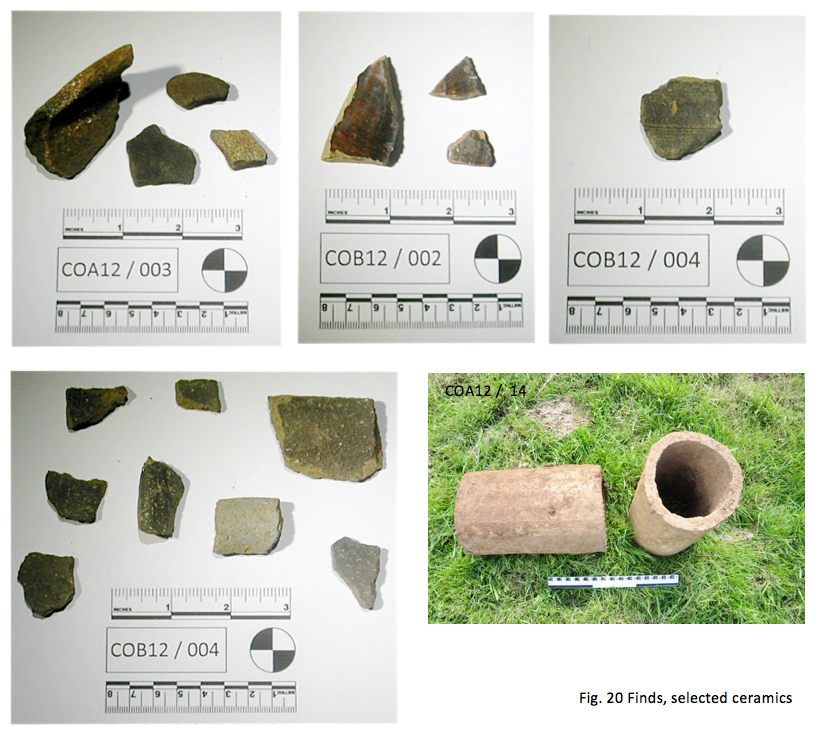

medieval pottery (Fig. 20) was recovered from the collapsed core of the wall. A

possible post hole was identified in the surface of 006 (008/009). There were

few finds associated with 006 except for a piece of iron (Fig. 21), possibly a

fragment of a horseshoe or patten and a single bovine phalanx (Fig. 9).

6.3 To the west of the wall the northern half of 002 was excavated. At a depth of around 50 cm this merged with a deposit containing rather less rubble but similar in composition (003). This change coincided with a shallow step in the west face of the wall core (007). Excavation of 003 was halted at a depth of 65 cm.

Fig. 12 Church Oakal B site, general view looking west (VW) Fig. 13 Church Oakal B site, general view looking east (VW)

6.4 Discussion

A large stone building was demolished here in the

first half of the eighteenth century, a date in accordance with the suggestion

that the structures were removed during the development of the Georgian park to

improve the view of the church from the game larder. That the demolition was

systematic is evidenced by the presence of a few damaged facing blocks

discarded amongst the rubble and the number of bent iron nails typical of sites

where timberwork has been dismantled.

6.5 Less clear is the function and layout of the

building. Given the collapse of the core it is difficult to give a definite

dimension but it must have been around a metre thick. By comparison with other

similarly constructed buildings in the location this suggests a large agricultural building such as a

barn or a major domestic structure such as a manor house. Further

interpretation is made difficult by the paucity of finds. To the west excavation

was halted at a level still within

the general build up of destruction material.

6.6 To the east the relationship between a

metalled surface and the wall remained unclear. The character of the surface

indicated either an outside yard or possibly an indoors hard-standing for

livestock rather than domestic use. The finds reinforced this impression.

However, what was remarkable is that the

collapsed wall material bedded down directly onto this surface with

little evidence of occupation layers between. This could indicate that the

building was taken down very shortly after the surface was laid or possibly

that deposits of manure had been removed prior to demolition. The possible

post-setting on the surface of the metalling could indicate the presence of a

timber partition. The stratigraphic relationship between the wall and the

metalling remains puzzling and it may be that what was identified as intact

core material was in fact slumped down from an intact core further to the west.

6.7 The most remarkable find was a collection of early medieval pottery spread throughout the rubble above the yard surface (Fig. 20). This must be derived from the material that was scraped together to form the core of the wall. The sherds are not heavily abraded and it seems likely that they were dug up in the vicinity, perhaps coming from any foundation work that was undertaken for the building. Although no precise parallel has been found for them in the Warwickshire type series they certainly resemble Saxon material from the nearby excavations at Burton Dassett and so offer the first archaeological evidence for early settlement at Farnborough.

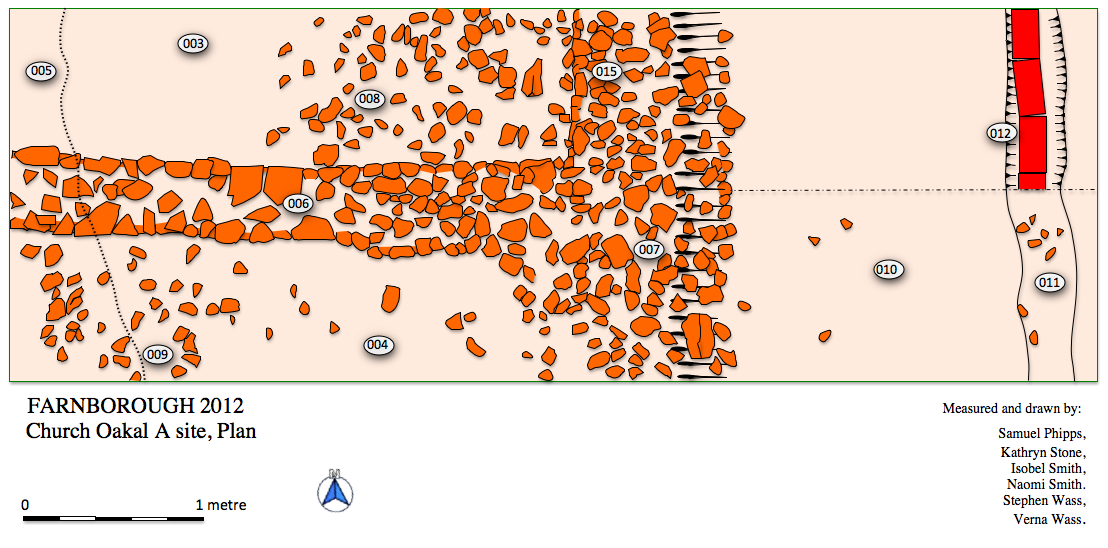

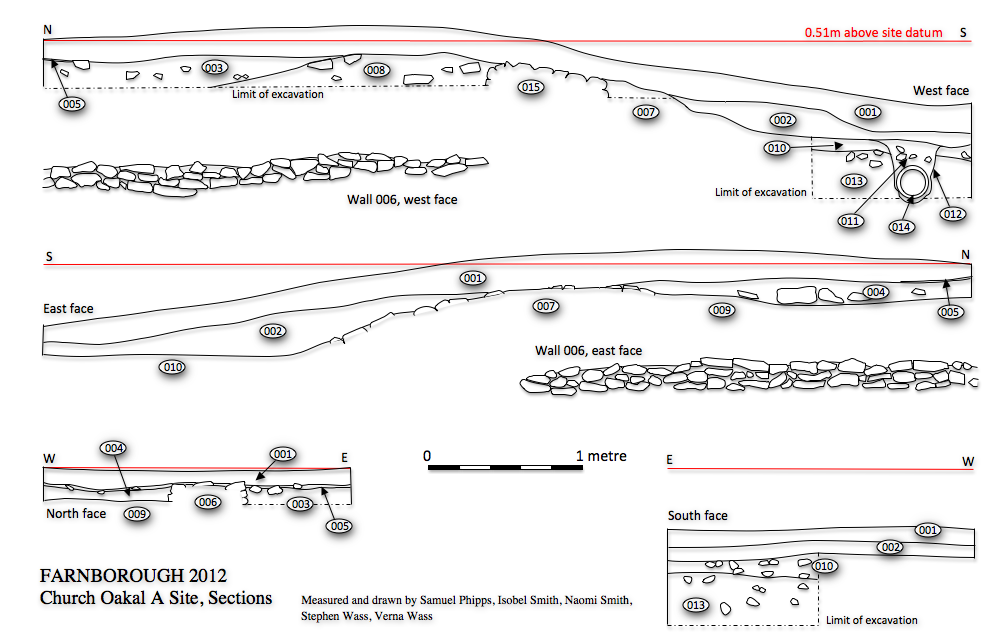

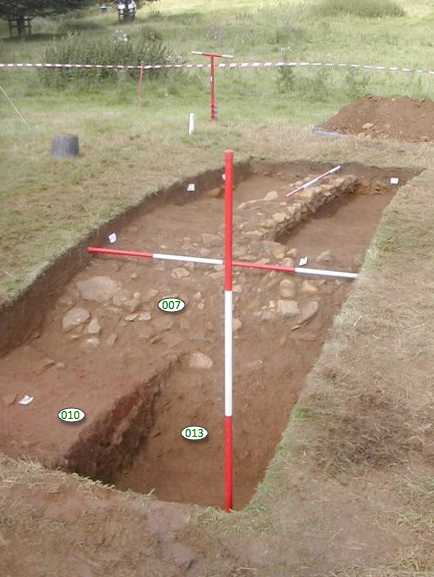

7.1 Results

The trench was situated so as to take in the

southern scarp slope to the central platform of the moat and the surface

profile reflects this. Underneath the turf and topsoil (001) was a layer of

rubble which on cleaning was resolved into a perimeter wall or revetment to the

moat (007) and smaller wall at right angles to this (006) surrounded by other

discrete areas of rubble. A thin layer of gravel spread into the trench from

the north below the top soil but above 006 and associated rubble levels.

7.2 The perimeter wall or revetment appeared as a

spread of rubble pressed into the face of the scarp (Fig. 17). It was composed

or both the more common brown ironstone rubble but with significant quantities

of the harder grey type much of which lay flat on the face of the bank.

Additional cleaning of 007 showed that there was a distinct edge of laid blocks

on the west side of the northern section (015). The uppermost blocks of this

walling exhibited well rounded tops evidence of erosion probably whilst exposed

on the surface of the ground.

The internal wall 006 was composed of ironstone

rubble laid in two or three irregular courses and roughly 40 centimetres

wide. The character of this wall

is strongly suggestive of a sleeper wall to carry a base plate for a timber

framed building (Fig. 16).

7.3 Layers of redeposited material to the east and

west of 006 were differentiated largely on the basis of varying concentrations

of rubble with 003 lying partially below 008 to the east and 009 below 004 to

the west. These layers seem to represent different phases of demolition and

deposition after the site was abandoned. A small amount of medieval pottery and

two microliths were recovered from these deposits. No occupation levels were

reached associated with either wall.

7.4 Beyond the revetment in the area of the moat was layer of rubble representing material (Fig. 19) eroded or thrown down from the bank (002) above two layers containing large quantities of brick rubble (010 and 013). These were cut by a narrow trench ( 011/012) for a run of large ceramic drain pipes (014).

Fig. 14 Church Oakal A Site, Plan of trench

Fig. 15 Church Oakal A Site, sections

7.5 Discussion

The key question to be addressed in exploring the nature of these earthworks is whether they represent the site of medieval occupation or are later garden features, although of course they could be both. Some medieval material was recovered from the site, although not in the quantities that would be expected from domestic use. This together with the extent walling suggest an ancillary building, perhaps agricultural in nature but part of a larger manorial complex. Although several fragments of burnt stone were recovered there was insufficient material to suggest the presence of a hearth nearby or that any structures had been damaged or destroyed by fire. The lack of finds which could plausibly be related to the building becoming derelict suggests the site may have been cleared systematically, indeed given the eroded nature of some of the surviving walling the site could have been left open post-abandonment and livestock introduced to the area. Probably in conjunction with the construction of the walled garden in the early nineteenth century a gravel, path was laid just to the north of the excavated area.

7.6 Given the preponderance of brick fragments it

seems likely that the moat was

partially filled and leveled during the early nineteenth century when

access was required across the area to take produce from the walled garden

through the tunnel to the west and round to the kitchens. A ceramic land drain

was laid to further improve drainage of the moat probably some time in the

middle of the century (Fig. 18).

7.7 Three microliths were found amongst the

spreads of rubble. They are typical of material from the Mesolithic in south

Warwickshire and indicate something of the settlement potential of the area

(Fig. 21).

Fig. 18 Church Oakal A Site, moat drainage looking south (VW)

Fig. 19 Church Oakal A Site, general view looking north (VW)

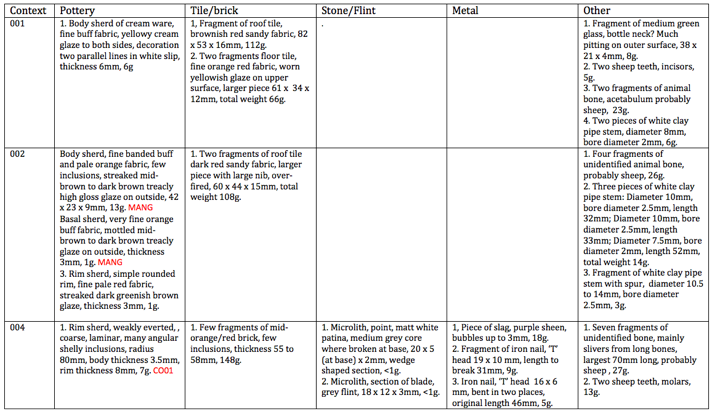

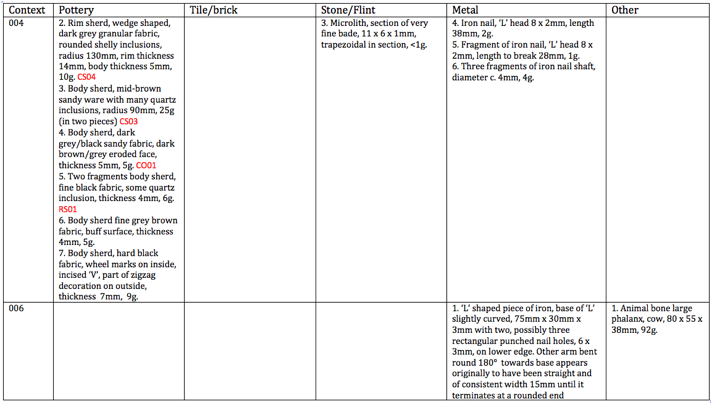

8.1 Church Oakal B site

8.2 Church Oakal A Site

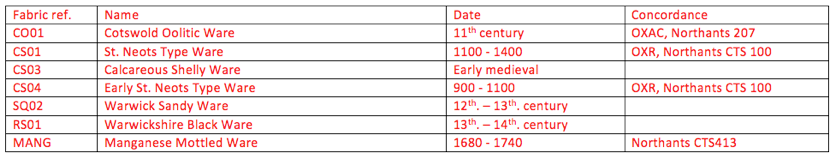

Pottery References – Soden

and Ratkai 1998

Fig. 21 Selected other finds

9.1 the presence of three confirmed and two

possible Mesolithic flints in a comparatively small area indicates a hitherto

unknown locus for early occupation. Field walking in the field immediately to

the south could clarify this.

9.2 Settlement, next to the church (Church Oakal B

Site) around at least one stone building has been demonstrated with a time span

from the early medieval period through to the first half of the eighteenth

century. Further work on the pottery could establish a closer date for the early medieval material.

9.3 The indications are that the earthworks in the

valley bottom (Church Oakal A Site) represent a medieval homestead moat

possibly associated with the original manor. There was no late or post-medieval

material associated with occupation on the site suggesting an early date for

the relocation of the hall to its existing location further west.

9.4 Improvement to the estate during the

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is evidenced by the demolition of the

building on top of the hill, the on-going measures to drain, fill and

consolidate the former moat and the laying of a path between the hall and

kitchen garden.

9.5 From a preservation point of view there are

clearly very significant archaeological remains close to the surface in a

number of locations. Although under no immediate threat consideration need to

be given to the grazing regime employed as there is clearly some damage to the

earthworks from cattle including one point where walling is being eroded out

from a bank and destroyed (Fig. 22).

9.6 The network of footpaths across the field is very well used by walkers, both local people and those who have come from further afield. An interpretive panel situated perhaps in the car park adjacent to the church, where there is a good view of the earthworks, could do much to enhance the community's appreciation and understanding of the sites.

10.1 the finds will remain in the estate office at

Farnborough Hall pending a decision on whether they are to be deposited with

the Warwickshire County Museum Service or be retained by the National Trust.

10.2 All original drawings, context sheets and

other notes will be deposited with the National Trust.

10.3 Copies of this report will be deposited with

the National Trust, the

Warwickshire Historic Environment Record, The Warwickshire Information and

Library Service, Banbury Museum and the Oxfordshire Library Service.

11.1 Many thanks to Janine Young and Richard White

of the National Trust for facilitating the work. Thanks to Verna Wass for

supervision and photography (VW) and to Chris Mitchell (CM) for photography.

Thanks to the team of volunteers who helped with the original survey work: Peter Braybrook, Stephen and Brenda Day,

Bob Ewing, Chris Miller and Geoff Parratt. Very special thanks to our

enthusiastic team of diggers: Samuel Phipps, Isobel and Naomi Smith, and

Kathryn Stone. Thanks to Cathy Coutts and staff at Warwickshire HER for help with

finds.

Aston, M. 1985. Interpreting

the Landscape, Landscape Archaeology in Local Studies, London: Batsford

Linnell, E. 1772. Farnborough Estate Survey, Warwickshire County Records Office Ref. z 403 (u)

Soden, I and Ratkai, S. 1998. Warwickshire Medieval and Post-medieval Pottery Type Series,

Northants Archaeology for Warwickshire Museum

Williams, B. J. 1975. Geology of the Country Around

Stratford-upon-Avon and Evesham: Explanation of 1: 50,000 Geological Sheet 200,

New Series (Geological Memoirs & Sheet Explanations (England & Wales)), London: Geological Sciences Institute

Radley, J. D.

2003. Warwickshire's

Jurassic geology: past, present and future, Mercian

Geologist, Volume 15, number 4, pages 209 to 218

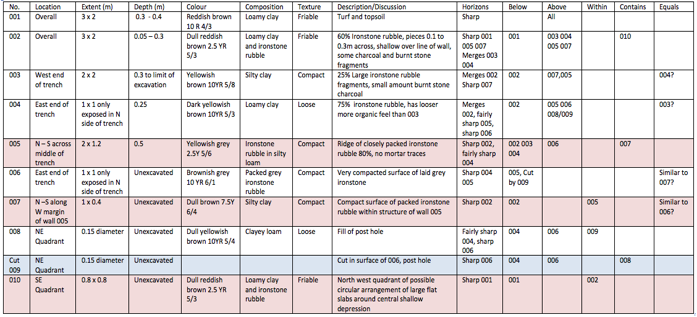

Appendix 1 List of Contexts

Church Oakal B Site