Farnborough Park and the 'Ethic of Improvement'

Back to Project

This is the slightly amended text of a paper written in September 2011 as part of my M.A. for the University of Leicester.

Fig.1

Introduction

In her ‘provocative’ (Schmidt 2009: 243 and Hicks 2008:111) book, ‘The Archaeology of Improvement’ (Tarlow 2007) Sarah Tarlow convincingly argues for a new category to be prioritized in developing accounts of social and technological changes in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: that of ‘Improvement’(Fig. 1). In this paper we will begin by briefly examining the term and the contexts in which it is employed, then, having given an outline history of the Farnborough Park, Warwickshire, we will explore in detail three instances of how the ethic of improvement shaped its landscape. Initially we will respond to Tarlow’s call for better understanding of water management by looking into drains and at patterns of water use within the park. Secondly we will explore aspects of the ‘Questions and Ambiguities’ with which Tarlow closes the book (Tarlow 2007: 197) by considering the topic of resistance and its effect on the physical world of Farnborough. Finally we will attempt to extend the initial concept by asking can Improvement be fun? In other words to what extent did philanthropic or economic concerns march hand in hand with the impulse to pleasure?

We will take it that for the purposes of this discussion the ‘ethic of improvement’ was characterised by, ’cleanliness, order, rational organisation, light and clarity. It demonstrated the ownership of rational knowledge and taste, a general orientation towards the future and a selective rewriting of the historical and classical past’ (Tarlow 2007: 67).

Improvement

One might be inclined to the view that the desire for and the drive towards improvement is a human universal, Tarlow however, is very specific about granting the term a capital letter and steering our view of Improvement towards the post-medieval period. She discounts, ’efforts at improvement in the middle ages’ on the grounds that they, ‘were directed inwardly to the soul of the individual’ (Tarlow 2007: 11) although one might want to balance that against on-going research into the development of medieval elite landscapes (for example Creighton 2005) or indeed argue that plenty of eighteenth or nineteenth century improvers were ‘in it’ for the good of their souls. However, this is a diversion from the main thrust of the argument that Improvement was an ethical imperative, which brought about wholesale transformations to the rural and urban landscape and which was founded on the idea of a new order – modernity. What is more, ‘The economic and moral meanings of the term became increasingly knitted together so that by the mid eighteenth century ‘Improvement’ meant both profit and moral benefit’ (Tarlow 2007: 12).

Tarlow goes on to list and analyse concepts which shaped and in turn were shaped by the ethic of improvement (Tarlow 2007:22 - 27). The first of these is utility as expressed through utilitarianism, a philosophy linked to promoting the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Second is society: expressed as linked networks of communities in which the improvement of one implied the improvement of all, although it is worth perhaps mentioning that improvers themselves may have had a more limited understanding of the term society. Society is followed by individual agency: the product of ‘financial independence and social power’ (Tarlow 2007:23) which in turn leads on to reason. Tarlow sees reason as not being opposed to religion but to tradition and custom as brakes on progress towards the next category that of Utopia, the ‘ultimate end of improvement’ (Tarlow 2007:26). Finally she describes class and social relationships as expressing the concrete actions of individuals and social groups through which Improvement came about. Some commentators have criticized Tarlow for not fully acknowledging the driving forces of capitalism and particularly the abuses of the slave trade which underpinned ‘the Georgian Order’ (for example Hicks: 2008:115). This criticism seems a little misplaced as she is clear that colonialism and capitalism whilst important factors were not the focus for ‘structured contemporary discourse’ (Tarlow 2007: 17) during the period and that the availability of capital did indeed come about ‘in large measure because of exploitative economic relationships with much of the rest of the world’ (Tarlow 2007: 198).

Farnborough Hall

Fig.2 Farnborough Hall from the north-east, Photo by Chris Mitchell

The Importance of Drains

Fig. 3 Recording a collapsed drain in Church Oakal Field

Any landscape has a variety of elements which can be acted upon by the improver: the form of the land itself, the planting that takes place upon it, the erection of buildings and other structures and, our main focus in this section, the way in which water is managed. Whilst quite well understood on the macro-scale Tarlow reminds us that more humble features, especially drains, have much to tell us, ‘The nature and progress of field drainage in Britain has not yet, sadly, been taken sufficiently seriously by archaeologists’ (Tarlow 2007: 61) although as ever the late Philip Rahtz proved to be the exception (Rahtz 2010: 63). Improvements in aspects of the management of water at Farnborough will be considered under three sub-headings:

i) The Drainage of Church Oakal.

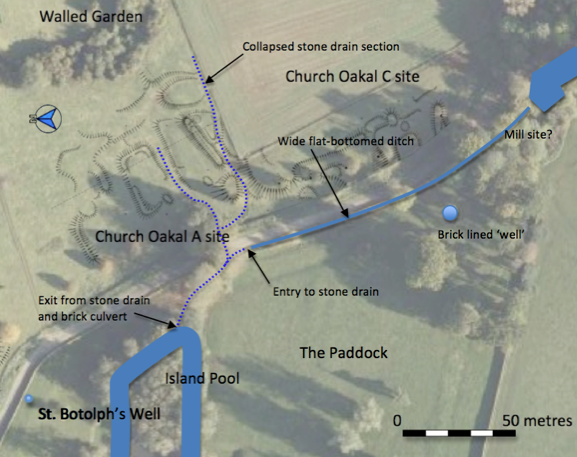

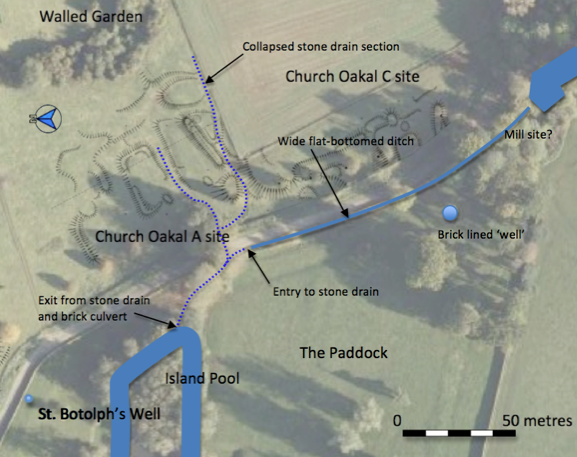

Fig. 4 Drainage features in Church Oakal and the Paddock

Church

Oakal is a field within the park which encompasses the hillside and

valley south of the church. Surviving earthworks strongly suggest the

presence of a small homestead moat and associated fishponds which could

represent the site of an earlier manor (Fig. 4). Whatever the case the

field is now drained and let out as pasture. Although a chronology has

yet to be firmly established we are assuming that the series of stone

lined drains (Fig. 3) represent an early attempt at drainage possibly

linked to the re-siting of the manor and the creation of a new park in

the early seventeenth century at the time of the first enclosures.

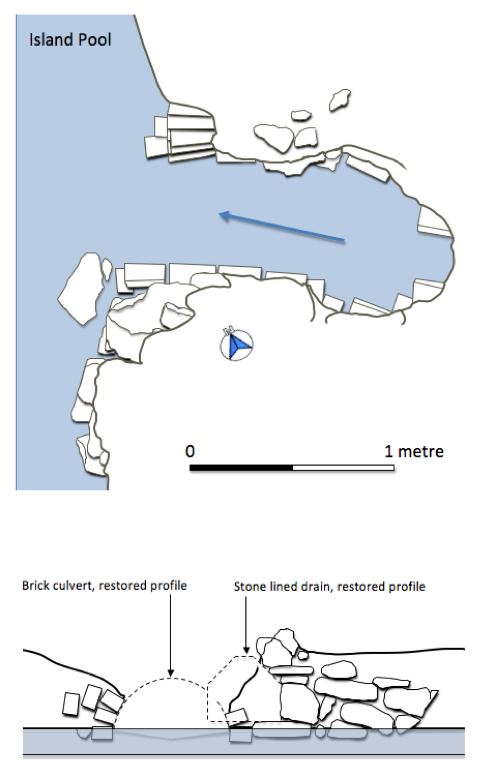

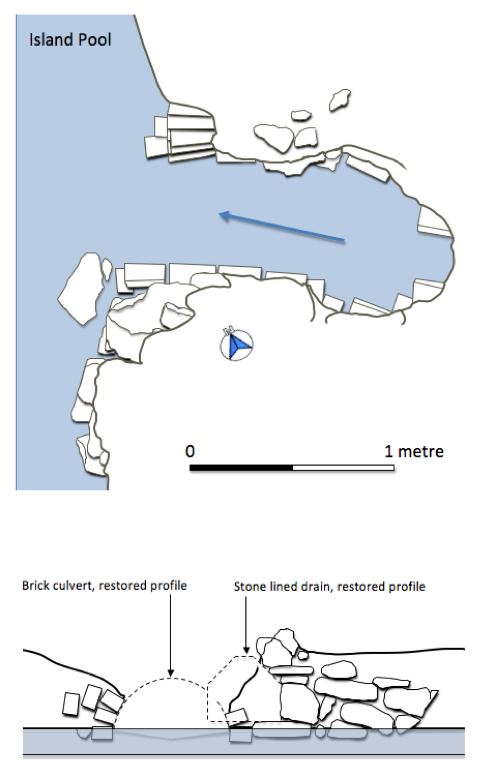

Although this is outside our time period we have also recorded the

presence of a brick lined culvert presumably of eighteenth century date

which cuts through the stone drain yet is at a lower level (Fig. 5)

indicating the partial success of the earlier scheme but with the need

to effect further improvements in the later period. In conjunction with

this it appears that typical of the period of Improvement were broad

flat bottomed drainage ditches also seen in the contemporary landscape

at Hanbury Hall – Warwickshire (Fig. 6). We are only at the beginning

of our study of the drains and culverts around the park but already it

is possible to evidence the drive for Improvement and the high priority

that drainage had in supporting this.

Fig. 5 Drains in the Paddock, plan and elevation from west

Fig. 6 Shallow flat bottomed drainage ditch in Hanbury Park looking north

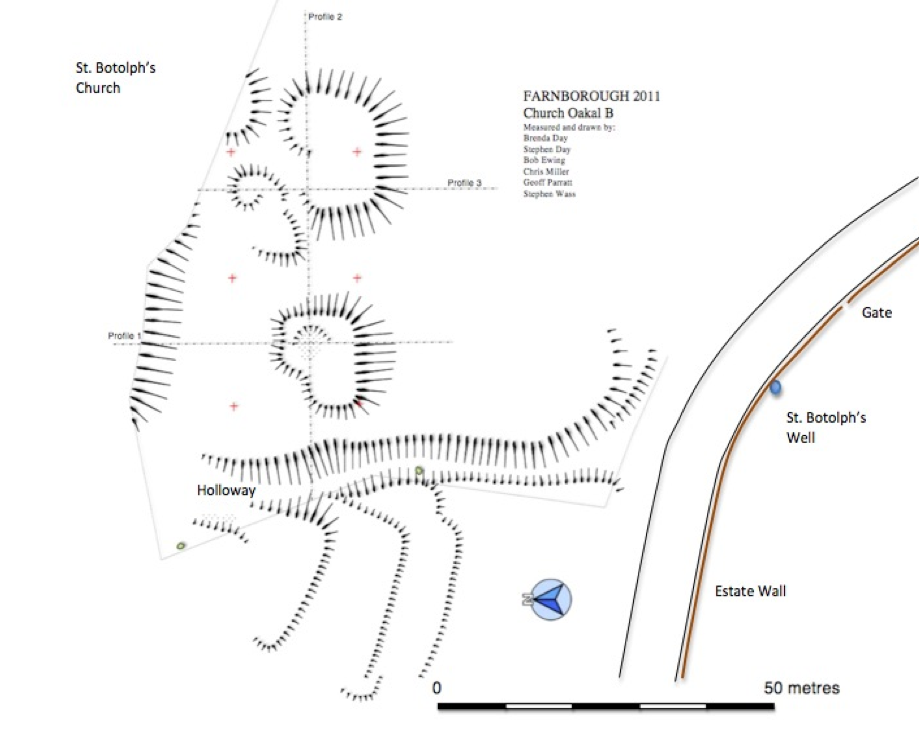

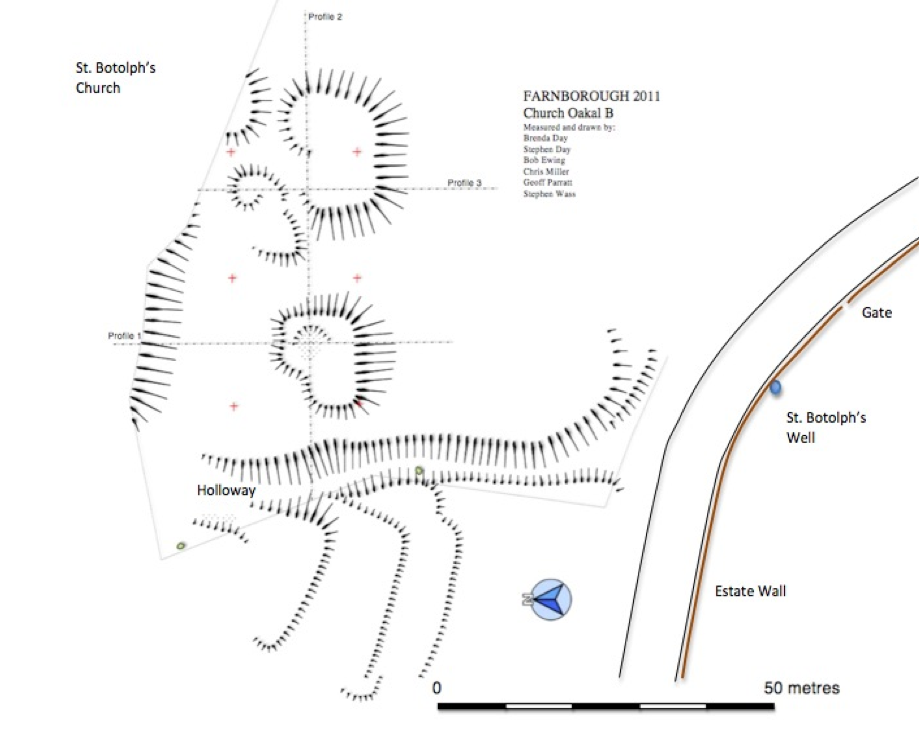

ii) The ‘privatisation’ of St. Botolph’s Well

Drainage of damp ground seems to be a measure which everyone wins by, from the landowner who will see improved yields to the labourers who find the daily round being eased by having less mud on their boots. However other improvements impacted on the villagers in less helpful ways. The northern end of Church Oakal field has a series of house platforms adjacent to the churchyard (Fig. 7), presumably cleared during the seventeenth century enclosure although the buildings they represent may have been demolished as part of an eighteenth century campaign to improve the view. Running down from the church is a pronounced holloway which lead to St. Botolph’s Well (Fig. 8). One must presume that the arrangement of church, holy well and connecting thoroughfare was an ancient one which reflected on the communal use of this spring for both practical and spiritual purposes. What is striking today about the spatial relationship is that the current park wall cuts across the bottom of the former route and effectively restricts access to the well (Fig. 9) as it is now on private property. A door in the wall was provided to allow some access – a door which by analogy to other local properties appears to be eighteenth century (Wood-Jones 1963) – but it is clear that the door could only be opened from the park side. What was communal has become private. The ethic of improvement in rural settings rarely seems to have been inclusive.

Fig. 8 Relationship between church, and well, view looking north-east. Photo by Chris Mitchell

Fig. 9 Plan showing house platforms, holloway and garden terraces and relationship to well

iii) The construction of the great Oval Pond

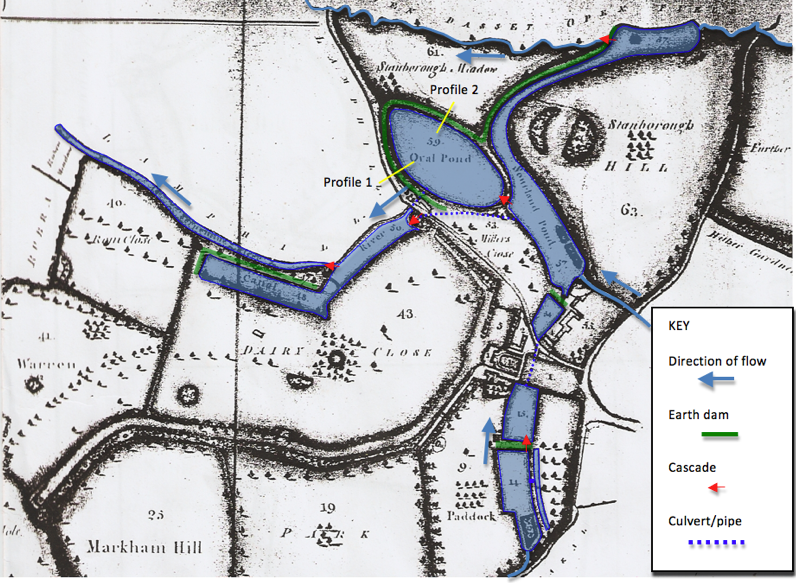

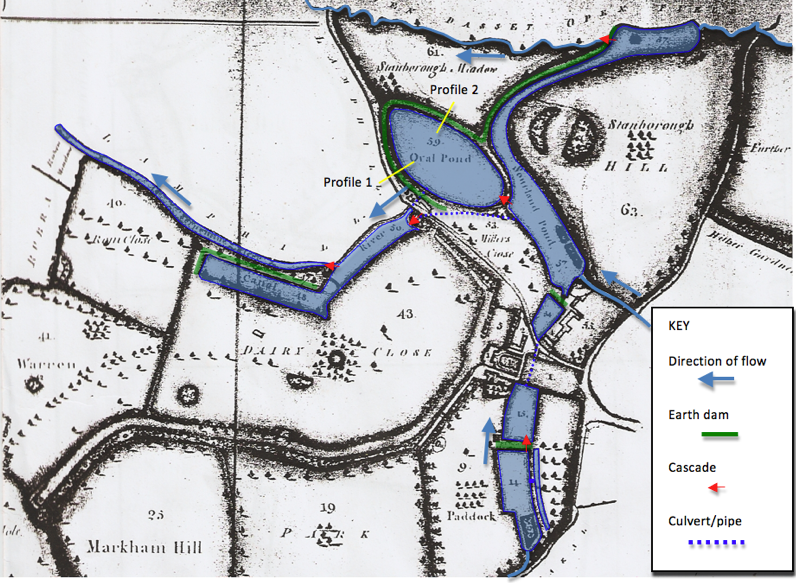

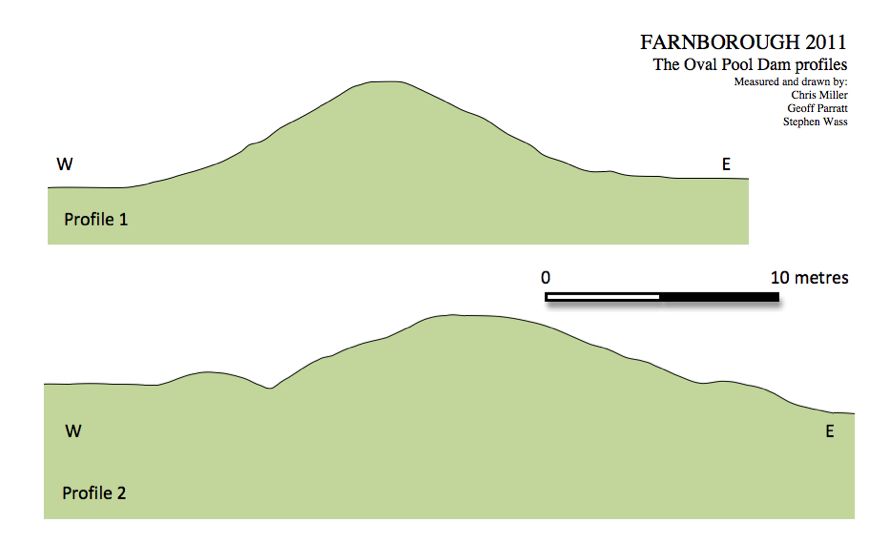

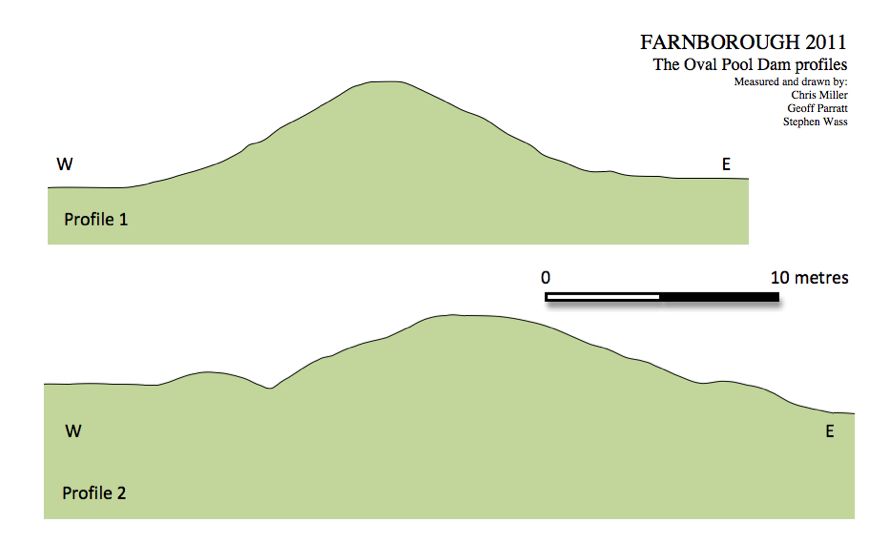

Considerable uncertainty exists as to the arrangements of the seventeenth century park which lay to the south of the present hall and the extent and date of the ‘deconstruction of (its) formal landscape’ (Currie 2005: 15). However surviving remains and in particular a late eighteenth century estate map ( Linnell 1772) enable us to gain an very clear picture of waterways and ponds post the eighteenth century Improvement (Fig. 10). The first point of note is the way in which all previous uses of water resources seem to have been declared redundant as the needs of the landscaped park took priority over earlier fishponds and mill sites – notably in Great Pool Close to the north-east where a series of ponds appeared to have been drained to provide the water for Sourland Pool and in the case of possible mill sites to the immediate north-west and more distant south-east of the hall (Fig. 5). This shaping of the physical world has been undertaken on a massive scale, it is hard to appreciate the sheer scale of the works and the total transformation of the landscape which they represent. A special case in point is the former Oval Pool (now drained, evidence of tree growth indicates this took place in the early twentieth century when the costs of maintaining the dams became too great). The easiest and most common way to create an impressive water feature is through the simple expedient of throwing a barrier across a valley as we see with the Island Pool and the River/Canal. However, the Oval Pool was actually built out across the flat valley bottom and retained by an enormous and undoubtedly costly earth dam (Fig. 11). Not so much improvement to the landscape as an imposition on it. What elements of the ethic of Improvement could support such an expensive transformation? Tarlow points out that, ‘it is easy to find numerous examples of landowners who spent vastly more money on enclosing, draining fertilizing and clearing their land than they were ever able to recover in increased rents’ (Tarlow:2007: 35) although one assumes the impulse was still nodding in the direction of economic advancement. Here, and of course in many other instances, we see ‘an awareness of beauty (‘taste’)’ and perhaps more winning out over ‘economic utility’ rather than being in partnership with it (Tarlow 2007: 75).

Fig. 4 Drainage features in Church Oakal and the Paddock

Fig. 5 Drains in the Paddock, plan and elevation from west

Fig. 6 Shallow flat bottomed drainage ditch in Hanbury Park looking north

ii) The ‘privatisation’ of St. Botolph’s Well

Drainage of damp ground seems to be a measure which everyone wins by, from the landowner who will see improved yields to the labourers who find the daily round being eased by having less mud on their boots. However other improvements impacted on the villagers in less helpful ways. The northern end of Church Oakal field has a series of house platforms adjacent to the churchyard (Fig. 7), presumably cleared during the seventeenth century enclosure although the buildings they represent may have been demolished as part of an eighteenth century campaign to improve the view. Running down from the church is a pronounced holloway which lead to St. Botolph’s Well (Fig. 8). One must presume that the arrangement of church, holy well and connecting thoroughfare was an ancient one which reflected on the communal use of this spring for both practical and spiritual purposes. What is striking today about the spatial relationship is that the current park wall cuts across the bottom of the former route and effectively restricts access to the well (Fig. 9) as it is now on private property. A door in the wall was provided to allow some access – a door which by analogy to other local properties appears to be eighteenth century (Wood-Jones 1963) – but it is clear that the door could only be opened from the park side. What was communal has become private. The ethic of improvement in rural settings rarely seems to have been inclusive.

Fig. 7 Church and house platform from south. Photo by Verna Wass

Fig. 8 Relationship between church, and well, view looking north-east. Photo by Chris Mitchell

Fig. 9 Plan showing house platforms, holloway and garden terraces and relationship to well

iii) The construction of the great Oval Pond

Considerable uncertainty exists as to the arrangements of the seventeenth century park which lay to the south of the present hall and the extent and date of the ‘deconstruction of (its) formal landscape’ (Currie 2005: 15). However surviving remains and in particular a late eighteenth century estate map ( Linnell 1772) enable us to gain an very clear picture of waterways and ponds post the eighteenth century Improvement (Fig. 10). The first point of note is the way in which all previous uses of water resources seem to have been declared redundant as the needs of the landscaped park took priority over earlier fishponds and mill sites – notably in Great Pool Close to the north-east where a series of ponds appeared to have been drained to provide the water for Sourland Pool and in the case of possible mill sites to the immediate north-west and more distant south-east of the hall (Fig. 5). This shaping of the physical world has been undertaken on a massive scale, it is hard to appreciate the sheer scale of the works and the total transformation of the landscape which they represent. A special case in point is the former Oval Pool (now drained, evidence of tree growth indicates this took place in the early twentieth century when the costs of maintaining the dams became too great). The easiest and most common way to create an impressive water feature is through the simple expedient of throwing a barrier across a valley as we see with the Island Pool and the River/Canal. However, the Oval Pool was actually built out across the flat valley bottom and retained by an enormous and undoubtedly costly earth dam (Fig. 11). Not so much improvement to the landscape as an imposition on it. What elements of the ethic of Improvement could support such an expensive transformation? Tarlow points out that, ‘it is easy to find numerous examples of landowners who spent vastly more money on enclosing, draining fertilizing and clearing their land than they were ever able to recover in increased rents’ (Tarlow:2007: 35) although one assumes the impulse was still nodding in the direction of economic advancement. Here, and of course in many other instances, we see ‘an awareness of beauty (‘taste’)’ and perhaps more winning out over ‘economic utility’ rather than being in partnership with it (Tarlow 2007: 75).

Fig. 10 18th. century water features superimposed on estate plan of 1772

Fig. 11 Profiles of dam to Oval Pool

Fig. 11 Profiles of dam to Oval Pool

Resistance

A recent reviewer remarked that, ‘many Marxian historical archaeologists would insist that power-resistance is the only game in town, and some would charge that Tarlow cannot problematize the trope in this way and still proclaim herself ‘sympathetic’ to ‘a broadly Marxist position’’ (O’Keeffe 2010: 150). However, Tarlow makes it clear that she is sensitive to such issues when she concludes the book with a series of important questions, notably, ‘How can we distinguish between a rejection of the ethic of Improvement and a rejection of any particular ‘improving measure’ and ‘was the ethic of Improvement an empowering ideology or a legitimatory tool of social control?’ (Tarlow 2007: 197). We are not yet in a position to answer these questions with respect to Farnborough but we can give some indication of the kinds of evidence available that may lead us towards a response. However, first it is important to register the difficulties in studying questions of resistance from an archaeological standpoint. Those who offer up resistance are those least likely to be in a position to effect major changes to the physical world: ‘In so far as the poor… inscribed their mark upon the land, it was in acts of vandalism or reappropriation which have left little direct trace in the archaeological record’ (Williamson 1999: 37). We have already noted the possible destruction of houses to the south of the church and the walling off of St. Botolph’s Well. Such events may well have been greeted with equanimity. It would be easy to fall into a narrative which features, ‘contests between hapless peasants and villainous landlords’ (Tarlow 2007:10) and perhaps the employment opportunities afforded by the construction of the park really did result in the following happy scene at Farnborough described by the poet Richard Jago:

‘Hear they her Master’s call? In sturdy Troops,

The Jocund Labourers hie, and, at his Nod,

A thousand Hands or smooth the slanting Hill,

Or scoop new Channels for the gath’ring Flood,

And, in his Pleasures, find a solid Joy.’

The Jocund Labourers hie, and, at his Nod,

A thousand Hands or smooth the slanting Hill,

Or scoop new Channels for the gath’ring Flood,

And, in his Pleasures, find a solid Joy.’

(Jago 1767)

Equally it is hard to imagine such a wholesale transformation of landscape could occur without, at the very least, some serious dislocation to everyday life within the

community and the inevitability of protest and complaint, albeit of a muted kind. In fact it is not until the nineteenth century that we begin to come across some evidence for resistance. In 1815 a large walled garden was built well to the south-east of the hall (English Heritage 2011) and a track running between the gardens and the kitchen

was taken under the lane to Banbury by means of a tunnel/bridge. The parapet which flanks the public highway is generously decorated with a variety of graffiti carved into the stone. The earliest date so far deciphered is 1881 although others could be earlier. The inscriptions speak of social – possibly even romantic – meetings memorialized by carving initials and other symbols such as handprints. What is interesting is that there are no instances of graffiti being carved upon lower parts of the structure which lie within the orbit of the park. This suggests that the local population felt comfortable with appropriating parts of the structure for self expression but the sway of the ‘big house’ was such that other seemingly more private spaces remained inviolate. Although it involves stepping into the twentieth century it is worth recording some other events, more invasive in their nature, which demonstrate a weakening in the hold of the elite landowners. On an obelisk of 1751, rebuilt in 1823 (Haworth 1999: 25), we see carvings undertaken by Italian prisoners of war hospitalized here during World War II and on an ancient beech adjacent to the cascade are cut the names of such rock and roll luminaries as Duane Eddy, Eddie Cochran and Cliff Richard and the Shadows. It is perhaps significant that Cochran died in 1960, the same year the hall was opened to the public after being given to the National Trust. Finally in a tumble down gardener’s bothy in the corner of the former orchard we have a cache of bottles indicating trespass and possibly illegal drinking in the 1970s or 80s. These items are important indicators of features we should be looking out for in our examination of the earlier park (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12 Images of resistance? Graffiti and empty bottles. Photos by Chris Mitchell

Can Improvement be fun?

‘Perhaps it is better to chance being wrong in an interesting way than right in a dull one’ (Deetz 1988 cited by Tarlow 1999: 469)

In responding to Tarlow’s point: ‘The problem [with] neo-Marxist historical archaeologies’[is that they] risk becoming simply another kind of reduction- ism, this time reducing the complexities of human actions, practices and thoughts to the strategic negotiation of power relationships, through the assertion of identity’ (Tarlow 2007: 9) one might wish to explore some of those complexities which have not as yet been fully accounted for within the ethic of Improvement. The majority of accounts of garden landscapes approach the subject from an art history background and are therefore strong on aesthetics and parallels with other art forms (Strong 1998 is an eminent example, Mowl 2010 is another), however, as Felus reminds us: ‘Much has been written about the designed landscape in the eighteenth century in terms of aesthetics, designers, literature and iconography, but little has been said about the way these landscapes and the buildings within them were actually used.’(Felus 2006: 22). Farnborough occupies a point between the, ‘a dream world of rococo fancy’ and the ‘insipid green acres’ of Lancelot Brown’s ‘bare and bald’ type of landscaping (Batey 1982: 6 – 7) and it is appropriate to ask what benefits the actual users of the park derived for they certainly were not economic ones. Indeed at the risk of being accused of being terminally post-structuralist I want to try and recreate imaginatively two aspects of the experience of Farnborough Park to attempt to determine whether or not there was fun in the landscape. Being aware of the dangers of projection and the easy assumptions one makes about the familiarity of the past I still believe that there are insights to be gained by appealing to common human impulses.

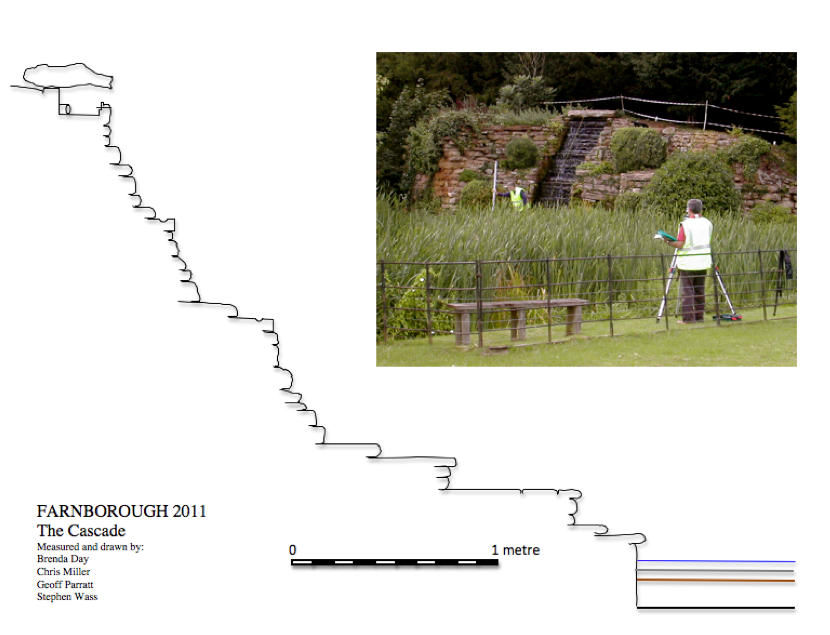

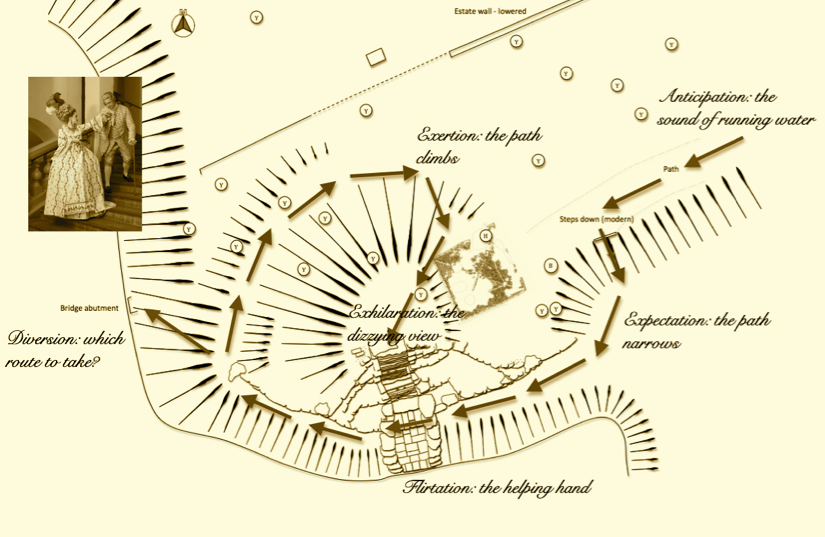

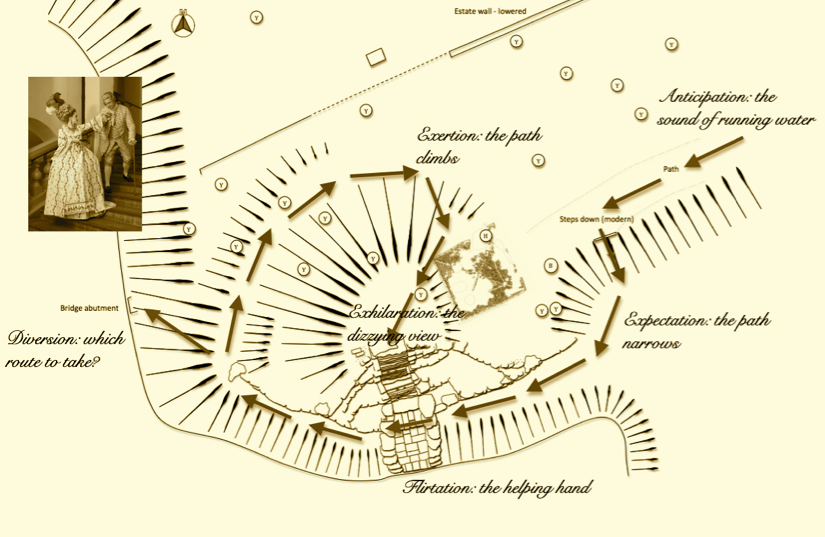

The cascade at Farnborough is a remarkable piece of Georgian construction but close acquaintance with it over the past few months has lead me to speculate as to how it was actually used and I have employed a number of visitors to test my assumptions. The first point to make is that despite being a major feature within the park the cascade cannot be easily seen from the house or any other major viewpoint. It is almost hidden away which suggests that an element of exploration and discovery was built into its situation. Modern visitors to the park are not allowed access to the cascade but can see it from a few metres away in a small fenced off area of park, yet even here there is something ‘ magical’ about the way in which, through clever hydraulic engineering, the water appears to bubble up from the highest point in the immediate landscape. Closer examination leads one along a path at the foot of a retaining wall to a place where the cascade bottoms out and the water flows across a series of broad shallow steps. These steps are well paved and the flow of water is organized so that at no point is it more than a couple of centimetres deep (Fig. 13). The impulse to walk across the bottom of the cascade at this point is almost irresistible. The presence of a socket for a possible hand rail indicates that this could have been an intentional element within the design. The path then spirals up behind the mound in which the cascade is set so that one can emerge at the top where once again the opportunity to step onto the cap stone and look down is extremely inviting. In the spirit of Burrow’s ‘structuralist approach to Bordesley Abbey’ (Rahtz 1985: 114) I offer an only slightly tongue-in-cheek eighteenth century visitor’s guide to experiencing the cascade (Fig. 14). Such an interpretation is not entirely without precedent; there are many recorded instances of garden features which were designed to trick, tease or thrill the visitor.

Fig. 13 Section through cascade and view from the south-east

Fig. 14 ‘The Lovers Plash’d’ an eighteenth century comedy of manners

Fig. 14 ‘The Lovers Plash’d’ an eighteenth century comedy of manners

Writing from the middle of the seventeenth century about hidden fountains at Wilton House near Salisbury which were ‘… like a plash’d Fence, whereby sometimes faire ladies cannot fence the crossing, flashing and dashing their smooth soft and tender thighs and knees by a sudden inclosing them in it’ (unattributed source in Strong 1997: 130) gives a powerful indication of at least one type of motivation behind such features. Thacker remarks that, ‘though our colder climate is hardly favourable to these Renaissance tricks they reappear from time to time, even in the eighteenth century’ (Thacker 1970: 20). By the eighteenth century, ‘fountains rarely appear, and the effects of tumbling water are displayed rather in natural cascades’ (Thacker 1970: 23). Perhaps here at Farnborough the ethic of Improvement is spiked by influences from seventeenth century ‘tricks and extravagances’. Whatever the case what is being posited here is the intention to create a feature which invites participation in a way which is as much to do with social interaction and enjoyment as it is with good taste.

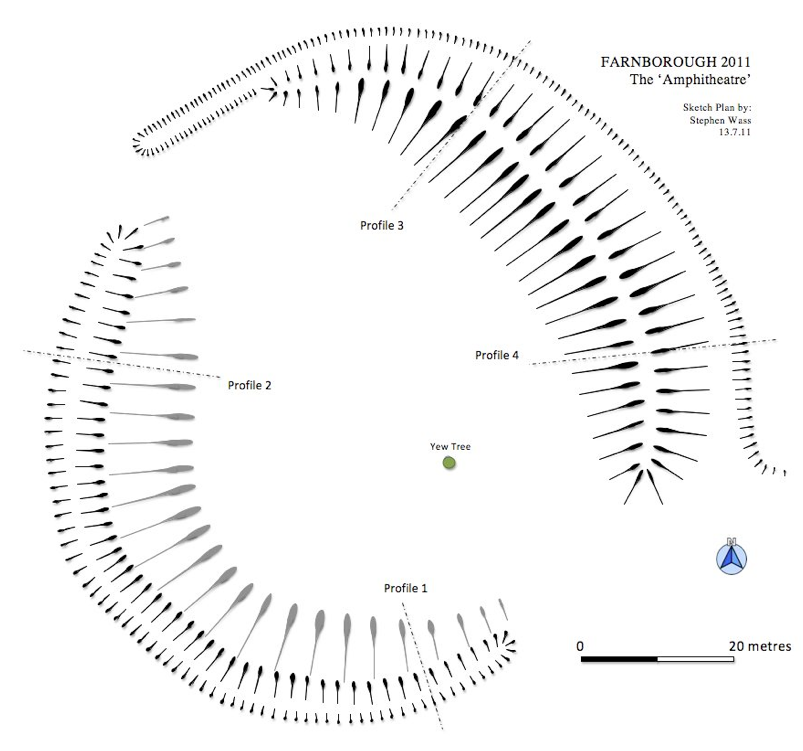

I believe a different sensibility is at work in the case of the Oval Pool which is designed to thrill more than titillate. Here as already noted this large area of water is confined by a dam which extends out from the natural hillside to create a great curving ‘bastion’ which dominates the valley beyond. The experience of walking out along the top of this dam must have been a remarkable one for at its furthest extent on the one hand one would have looked down to this large enclosed body of water whilst on the other would be a drop of some thirty feet to surrounding farmland which then stretched out across the adjacent open fields of the neighbouring villages. On one hand the pleasures of boating, on the other the rewards of hard labour but above all this the spectacle of a landscape not so much tamed as wrenched out of any pretence at normality or naturalness! It seems likely that pleasure boats were kept on here, it was a common feature of eighteenth century parks (Fig. 1). Felus’s thoughts about Wrest Park where , ‘we can see smaller craft on the canals, particularly the Leg o' Mutton Lake, which is overlooked by the amphitheatre that was used for theatricals, invites the speculation that boats might have played their part in the general entertainment’ (Felus 2006: 35) become especially relevant in the context of the newly discovered ‘amphitheatre’ (Figs. 15 and 16) at Farnborough. Although largely speculative I believe we have done enough to raise the possibility that major modifications to the landscape whilst coming under the blanket term Improvement actually owe something to notions of emotional experiences and social interactions that extend Tarlow’s original characterisation of the impulses behind the process.

Fig. 15 The Farnborough ‘Amphitheatre’ sketch plan

Fig. 16 The Farnborough ‘Amphitheatre’ profiles

Conclusion

Perhaps because of its comparatively early date the ethic of Improvement at Farnborough is not as strongly expressed as it would be in later decades. Although Improvement must have been part of the zeitgeist of the times other factors relating to the individuals who shaped the landscape at Farnborough also had a contributing influence. William Holbech as the commissioning landowner had, according to family tradition, been ‘disappointed in love’ (Haworth 1999:4) an event which apparently provoked his lengthy sojourns in Italy and consequently his passion for classical detailing. On the other hand Sanderson Miller whilst being an enthusiastic encloser and ‘at the cutting edge of the development of... “modern taste”’ (Meir 2002: 25) was also a medievalist with a keen sense of local history. One can speculate that a creative tension between these two contributed something to those aspects of the park’s design that seem to put them rather behind the curve and even seem a little old fashioned such as the rococo sense of fun and surprise and the rather out-moded amphitheatre.

Nevertheless as an early example of Improvement Farnborough demonstrates that the element of economic utility was well served, ‘the emphasis was on improvements which fitted in well with the agricultural scene, contributing to it materially as well as aesthetically’ (Meir 1997:98). The drainage of the old manor site together with the great curving pool situated on and named after ‘Sourland’ and the siting of the great terraced walks on the windswept crest of the hill slopes all speak of a desire to capitalize on marginal land. The appropriation of communal resources figures largely in the narrative of Farnborough and we have begun to get a glimpse of patterns of resistance and finally we have suggested that the moral purity of the ethic of Improvement was slightly subverted by a lingering commitment to rococo trickery and its attendant sense of fun.

It is interesting to reflect on all this in the light of modern attitudes towards improvement and specifically to the arrival of the M40 in 1990. The guidebook and other printed material available on the tour of the house rail at some length about the ‘vile’ M40 and ‘the views, now spoilt forever by the motorway’ (Haworth 1999:20). The irony is inescapable: Improvement from the eighteenth century and its ethic and its physical transformations were and still are trumpeted abroad and celebrated – contemporary improvements must be hidden away.

Bibliography

Batey, M. 1982 The Evolution of the English Landscaped Park Landscape Research Volume 7 number 1 pages 2 – 8

Creighton, O.H. 2005. Castles and Landscapes, London: Equinox Publishing

Currie, C. 2005 Handbook of Garden Archaeology York: Council for British Archaeology

English Heritage 2011 Farnborough Hall, Banbury, England, Record Id: 1304 Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest http://www.parksandgardens.ac.uk/component/option,com_parksandgardens/task,site/id,1304/tab,history/Itemid,305/

accessed 12.9.2011

Felus, K. 2006 Boats and Boating in the Designed Landscape, 1720-1820 Garden History Volume 34 number 1 pages 22 - 46

Haworth, J. 1999 Farnborough Hall, London: National Trust

Hicks, D. 2008 Improvement: What Kind of Archaeological Object is it? A Review Article Journal of Field Archaeology Volume 33 number 1 pages 111 – 116

Jago, R. 1767 Edge-Hill, or the Rural Prospect Delineated and Moralised, London

Linnell, E. 1772 Farnborough Estate Survey Warwickshire County Records Office Ref. z 403 (u)

Meir, J. 1997 Sanderson Miller and the landscaping of Wroxton Abbey, Farnborough Hall and Honnington Hall Garden History Volume 25 number 1 pages 81 – 106

Meir, J. 2002 Development of a Natural Style in Designed Landscapes between 1730 and 1750: the English Midlands and the Work of Sanderson Miller and Lancelot Brown Garden History Volume 30 number 1 pages 24 - 48

Meir, J. 2006 Sanderson Miller and his Landscapes, Chichester: Phillimore

Mowl, T. 2010 Gentleman Gardeners: the Men Who Created the English Landscape Garden Stroud: The History Press

O’Keeffe, T. 2010 Review Cambridge Archaeological Journal Volume 20 number 1 pages 148 – 154

Rahtz, P. 1985 Invitation to Archaeology, Oxford: Blackwell

Rahtz, P. 2010 Living Archaeology, Stroud: The History Press

Schmidt, A. J. 2009 Review Journal of Social History Volume 43 number 1 pages 242 - 243

Strong, R. 1998 The Renaissance Garden in England, London: Thames and Hudson

Tarlow, S. 1999 Capitalism and Critique Antiquity Volume 73 Number 280 pages 467 – 470

Tarlow, S. 2007 The Archaeology of Improvement in Britain 1750 – 1850, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Thacker, C. 1970 Fountains: Theory and Practice in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries Occasional Paper – Garden History Society Number 2

Salzman, L.F. (Ed) 1949 A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 5 Kington Hundred, London: University of London, Victoria County History pages 84 – 88

Williamson, T. 1999 Gardens, Legitimation and Resistance International Journal of Historical Archaeology Volume 3 number 1 pages 37 - 52

Wass, S. 2011 The Farnborough Park Project http://www.polyolbion.org.uk/Farnborough/Project.html

Wood-Jones, R.B. 1963 Traditional Domestic Architecture of the Banbury Region, Manchester: Manchester University Press