By Stephen Wass

Back to Project

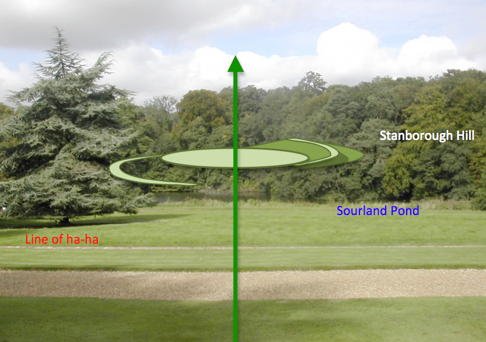

Fig. 1 Ducks on Sourland Pond

Submitted for the degree of Master of Arts, Historical Archaeology

School of Archaeology and Ancient History

University of Leicester

September 2012

ABSTRACT

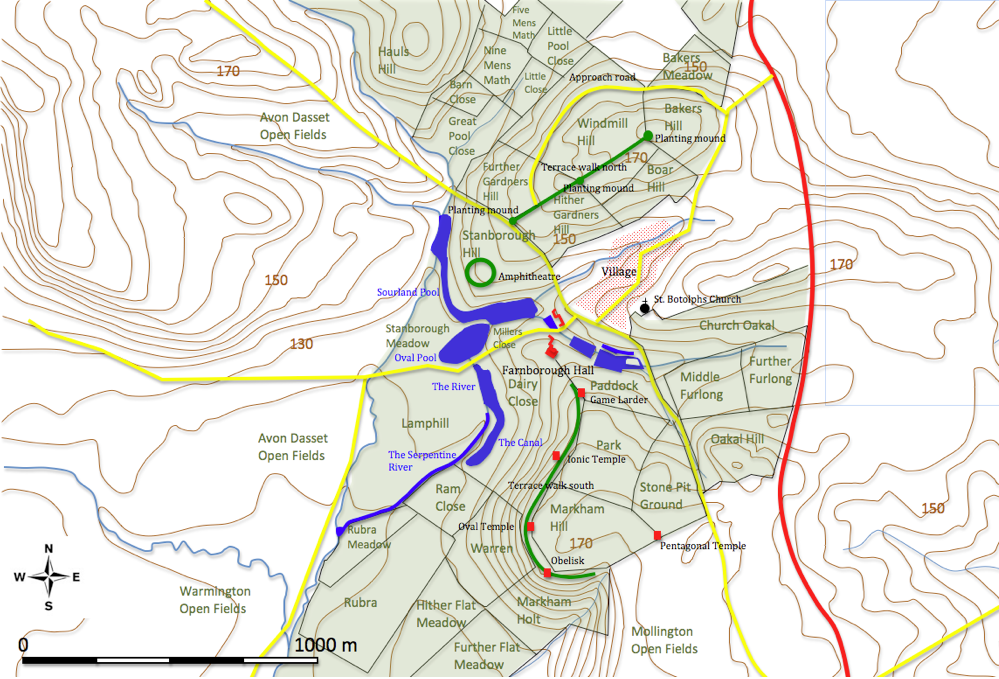

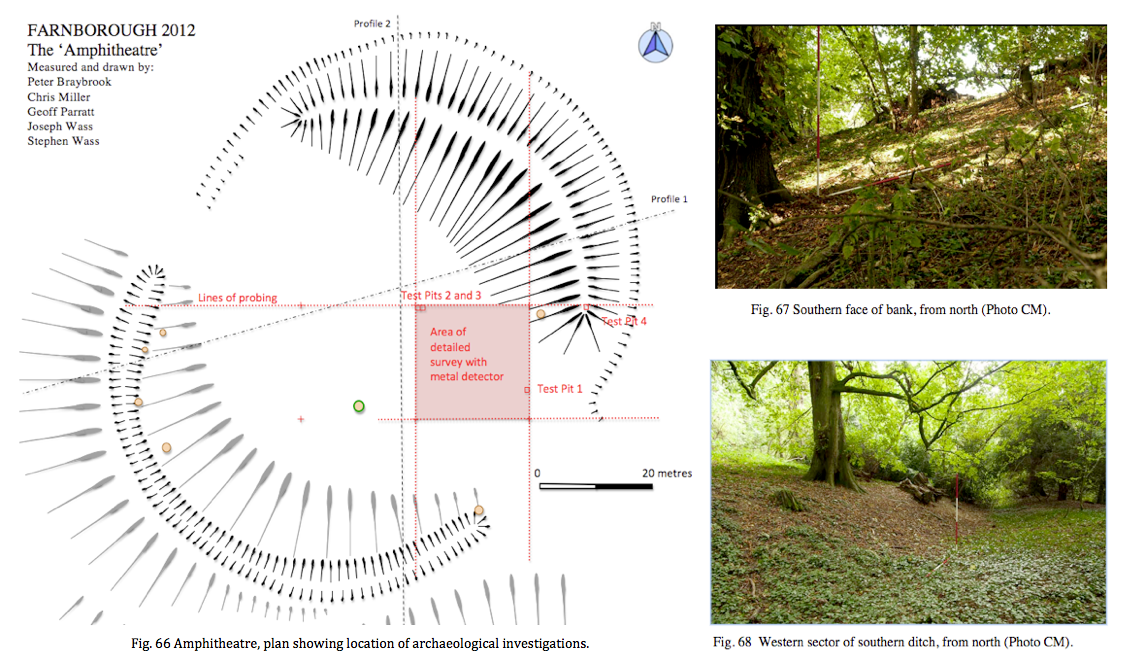

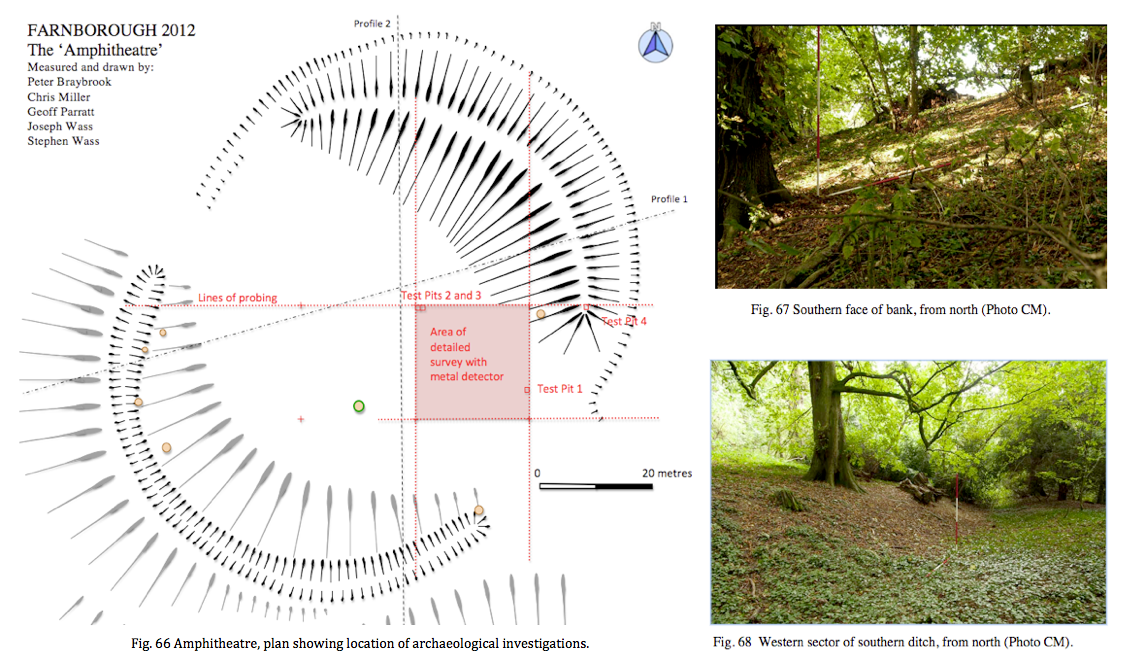

The park around Farnborough Hall, Warwickshire contains sites and monuments from the early medieval period onwards. Many of these are to do with the use and management of water. This account, mainly based on these remains, adopts an object biographical approach to tell the story of the changing ways in which water resources have been exploited, beginning with an examination of environmental factors, the early history of the park and its creation in the seventeenth century. A detailed account of the development of the Georgian park under the aegis of two individuals: William Holbech, the landowner and Sanderson Miller a gentleman architect, looks at factors which influenced the design of the park, documents a number of surviving structures and examines some of the technical aspects of construction. A number of highly unusual features have been recorded including a garden amphitheatre, a large raised pool and an elongated waterway which shares some characteristics with early river navigations. The consideration of the options available to both the work force and the social elite who shared the park explores the divide between labour and leisure. Debates about legitimation are considered and patterns of use and ownership expressing inequalities of power and social dominance are traced through to the present day.

The park around Farnborough Hall, Warwickshire contains sites and monuments from the early medieval period onwards. Many of these are to do with the use and management of water. This account, mainly based on these remains, adopts an object biographical approach to tell the story of the changing ways in which water resources have been exploited, beginning with an examination of environmental factors, the early history of the park and its creation in the seventeenth century. A detailed account of the development of the Georgian park under the aegis of two individuals: William Holbech, the landowner and Sanderson Miller a gentleman architect, looks at factors which influenced the design of the park, documents a number of surviving structures and examines some of the technical aspects of construction. A number of highly unusual features have been recorded including a garden amphitheatre, a large raised pool and an elongated waterway which shares some characteristics with early river navigations. The consideration of the options available to both the work force and the social elite who shared the park explores the divide between labour and leisure. Debates about legitimation are considered and patterns of use and ownership expressing inequalities of power and social dominance are traced through to the present day.

PREFACE

This study is the culmination of a two year contract with the National Trust to survey and record the archaeological features associated with the eighteenth-century park at Farnborough, Warwickshire. The project has been developed with the assistance of a team of volunteers many of them drawn from local heritage groups. The programme of study has been supported by a number of small scale excavations and documentary research, primarily at the Warwickshire County Record Office, where a copy of the archive will be deposited in addition to the material going to the National Trust.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to:

Richard White, gardener at Farnborough and his staff and team of volunteers for continual support both practical and moral;

Hesather Aston and Julie Smith both of the National Trust for oiling wheels

Jeremy Milln, former archaeological advisor to the National Trust for first seeing the potential of this project and to his successor at the Trust, Janine Young, who has supported the work in so many ways;

Professor Timothy Mowl, Dr. Jennifer Meir and Diane James M.A. for discussing aspects of the work with me;

the many villagers who have expressed interest in and support for the work;

the indefatigable team of volunteers including Peter Braybrook, Stephen and Brenda Day, Bob Ewing, Chris and Linda Leslie, Bryan Martin, Chris Miller, Geoff Parratt, Samuel Phipps, Isobel and Naomi Smith, Kathryn Stone, Verna Wass and Joseph Wass.

... and, of course, thanks to the Holbech family for everything else...

CONTENTS

Chapter 1 Introduction

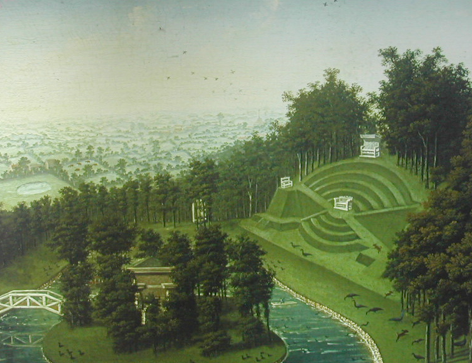

Fig. 2 Farnborough Hall, north front c. 1750. (Photo CM).

The landscape around Farnborough Hall, Warwickshire (Fig. 2) is a remarkable one with sites representing periods from the early-medieval onwards. It contains an hitherto unrecognized garden amphitheatre, a very unusual large raised oval pool and an extraordinary artificial river. The richness of this landscape enables a biographical study of water to be undertaken within a closely defined area. The notion of gaining understanding of the materiality of culture through ‘object biographies’ retains its currency more than ten years after the publication of Marshall and Gosden (1999) and the idea continues to be developed (Joy 2009). It is an extension of this concept to adopt a chronological approach, in effect, ‘telling the story’ of the interaction between the water in this landscape and those who used it.

The archaeological study of water is further enlivened by Wittfogel’s (1957) conjecture that the growth of ruling elites is connected to the control of water resources. This has informed the study of large scale hydraulic engineering and irrigation linked to social and geopolitical developments (for example Harrower 2009 or Sulas et al 2009). Microanalyses of the implications for smaller communities are less frequent, with Sayer’s (2009) excavations at Swavesey and Burwell being a notable exception. This project provides an opportunity to examine the use of water resources over an extended period with a particular emphasis on the controlling influence of social and cultural elites.

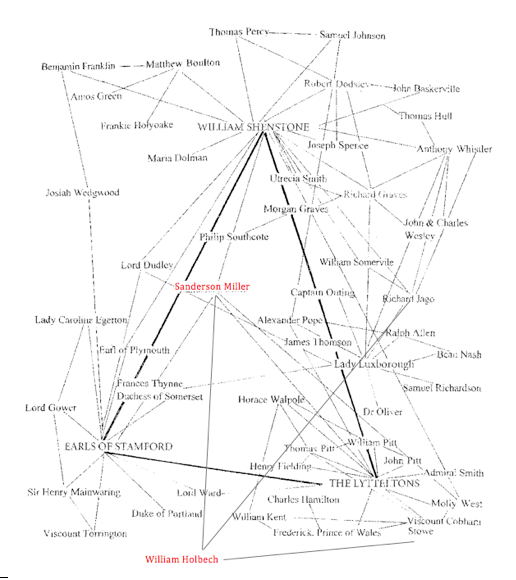

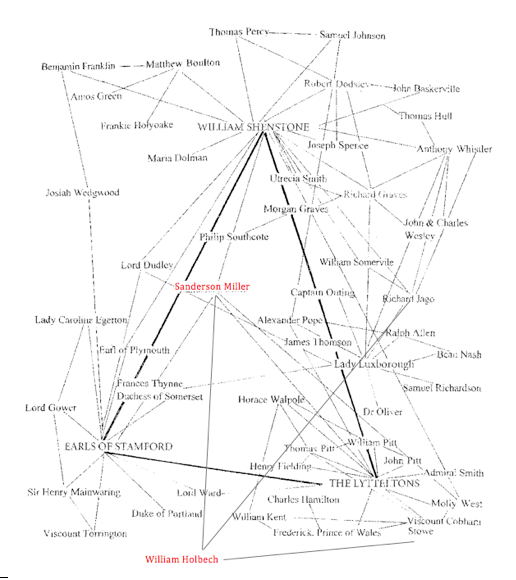

Fig.3 Sanderson Miller

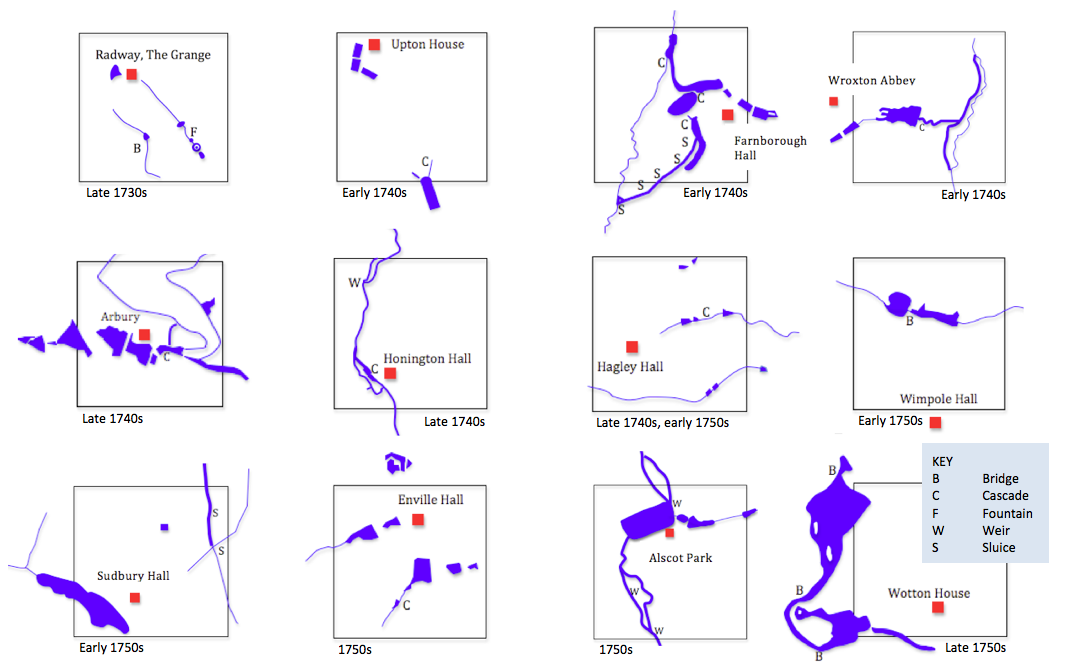

The most revealing episode in the biography of Farnborough’s water occurs in the 1740s when there was an extensive remodeling of the park attributed to the enigmatic figure of amateur architect, Sanderson Miller (Fig. 3) and his patron William Holbech. These personalities of the mid-eighteenth century intersect with our watery flow in a way which is revealing in terms of a better understanding of changing relationships between the uses of water and patterns of power and dominance. There have been many discussions about the relationship between individuals and the arc of history (Trigger 2006: 386 to 480). However, there is a widespread acceptance that significant developments in English landscape design happened as the result of partnerships between wealthy landowners and professional gardeners many of which are well documented (Mowle 2010). What makes the role of archaeology at Farnborough significant is the paucity of written records, a situation which can be partially remedied by a study of surviving monuments.

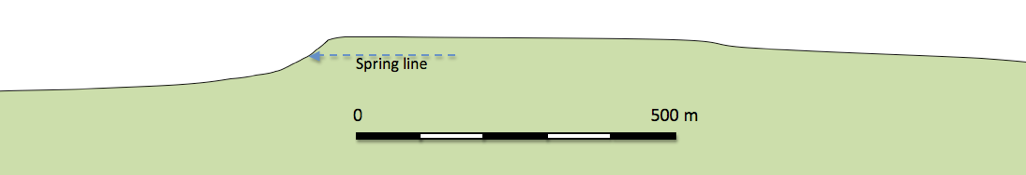

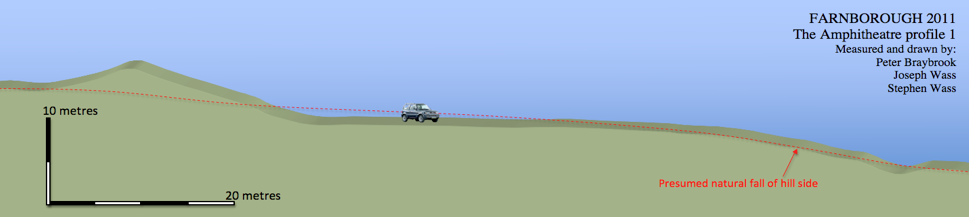

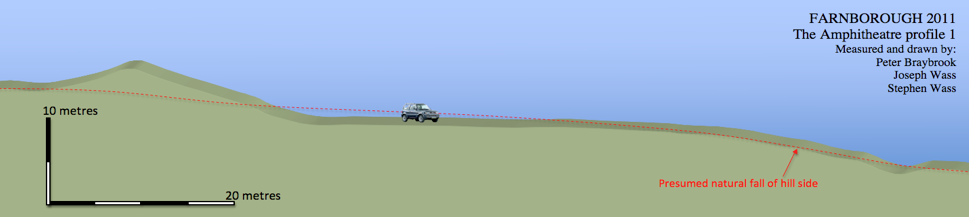

Fig. 4 Profile scarp and dip slope (see Fig. 5), vertical scale times 2.

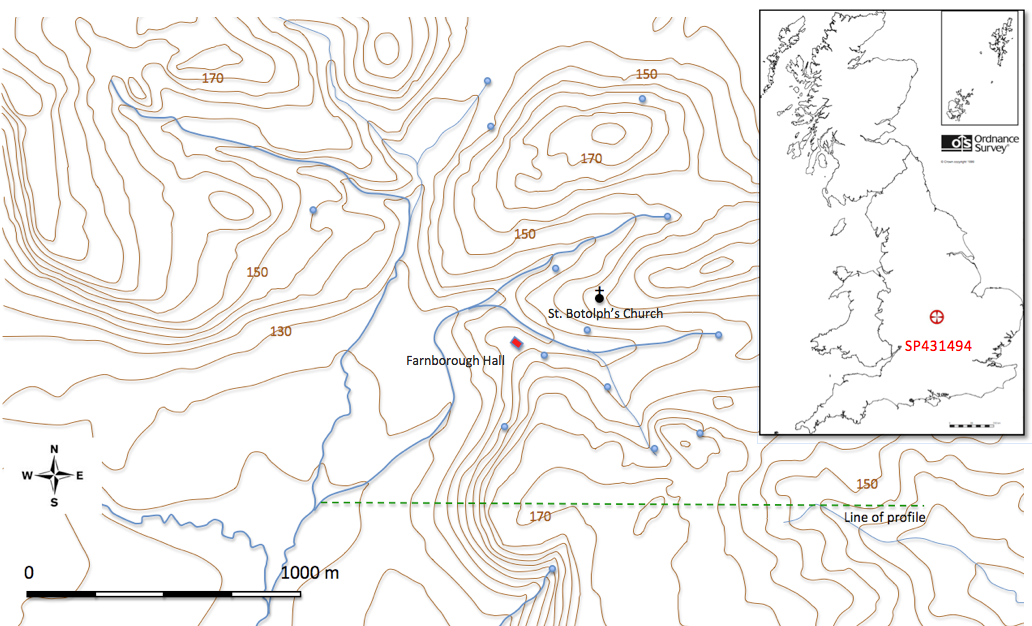

Fig. 5 Farnborough Park, location: contours, springs and streams, from OS 1:25,000 map.

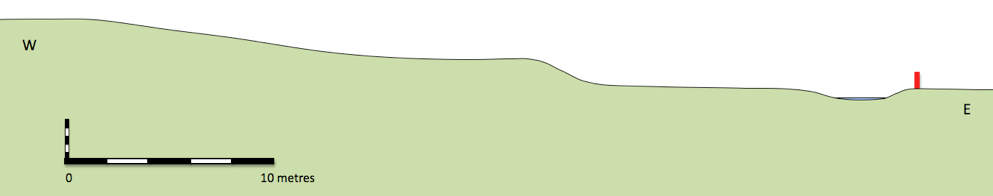

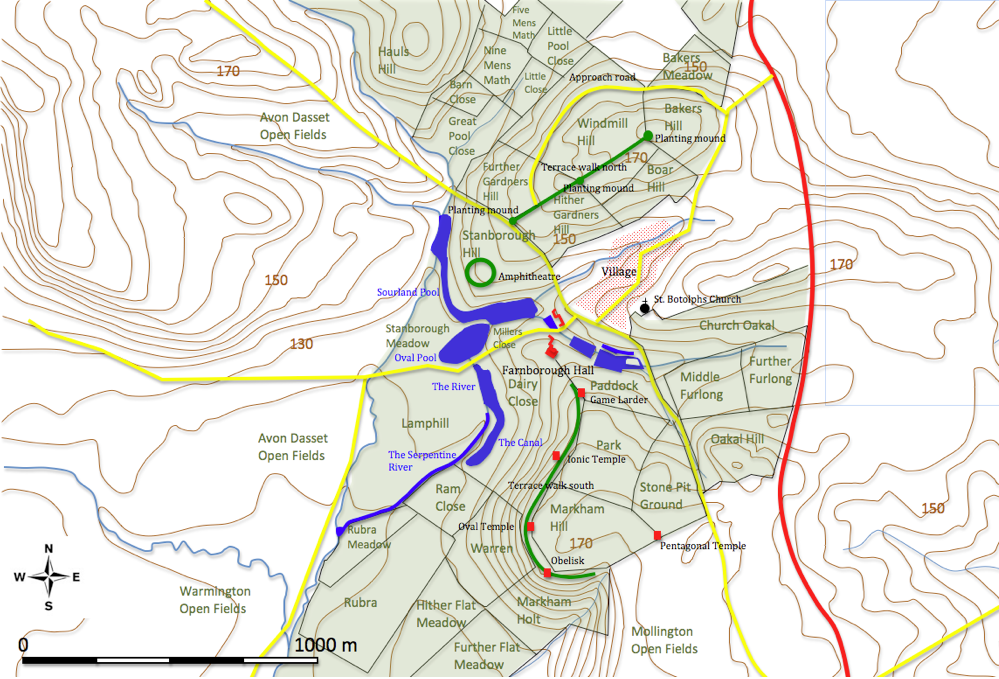

Farnborough lies on a northern outlier of the Cotswolds: a southern tilting mass made up of early Jurassic marine shales, limestones and sands of the lias group. The most prominent part of these deposits is a marlstone bed, which is a calcareous, sandy ironstone and due to its relative hardness, forms an elevated ridge (Williams 1975). Because of this the initial fall of the scarp is quite steep (Fig. 4) with an overall height of around 40 metres. The rusty brown ironstone has been widely used locally for building (Radley 2003: 209).

The scarp, running north-west to south-east, is dissected by a number of streams which come together to the south-west of the hall forming a re-entrant angle of low ground, sheltered by heights to the north and east (Fig. 5). The lower slopes consist of hill-wash and eroded material derived from the underlying marlstone, whilst the flatter plain to the south-east is composed of alluvial deposits of silt, clay and gravel, of periglacial origin.

There are several springs in the area, mainly clustered between the 145 and 160 metre contour. Some of these exist as depressions in the face of the hill-side from which water seeps, whilst others have been given some additional structure as at St. Botolph’s Well (Fig. 9) or the spring in the corner of The Paddock, which was enclosed in an octagonal brick wall (Fig. 21).

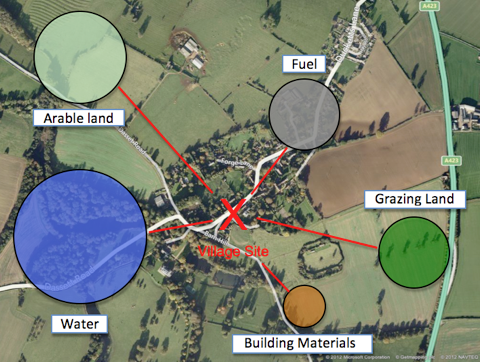

Fig. 6 Natural resources, ’weighted’ according to the likely importance to villagers (after Chisholm 1979:103)

Fig. 7 Church and house platform, from south

Fig. 7 Church and house platform, from south

Farnborough, in its earliest recorded form of Ferneberge, means Fern Hill (Duignan 1912: 56), an appropriate description for a village on a ridge flanked by two marshy valleys (Fig. 5). The location is typical of settlements on the fringes of the upper Cherwell valley such as nearby Mollington and Warmington which may have been founded in the seventh century by groups of immigrants who had spread across central England (Blair 1994: 42). A recent excavation south of the church has uncovered early medieval pottery which could be pre-conquest (Wass 2012b).

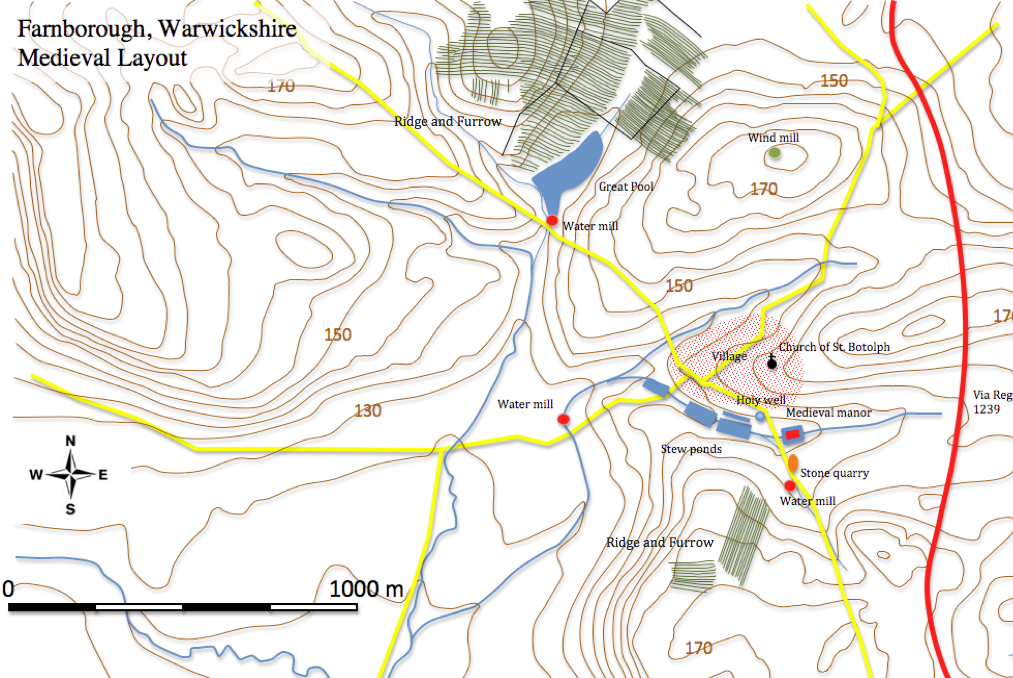

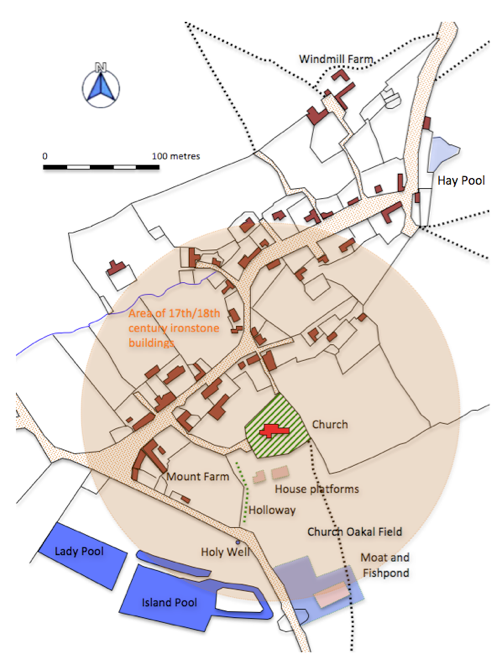

Fig. 8 Medieval settlement.

The settlement was sited to take advantage of the natural resources important to sustain life (Fig. 6). It is indisputable that water was a vital factor in the location of any settlement and not just for utilitarian reasons. Roberts reminds us of the less material factors governing the situation of villages and, given the particular prominence of the church (Fig. 7), one must acknowledge cultural factors at work (Roberts 1987: 106), some of which may give a sacred dimension to the landscape. This links to the matter of water supply given the proximity of the holy well of Saint Botolph (Fig. 9). At Domesday Farnborough was inhabited by eighteen villagers, one small holder and two servi. The manor, held by the Bishop of Chester, passed to the Say family then, in the mid-fourteenth century, to the Raleghs (Salzman 1949: 84). St. Botolph’s church, primarily fourteenth century, has a twelfth-century south door and chancel arch (Pevsner and Wedgwood 1986: 292).

Fig. 9 St. Botolph’s Well, from south-west.

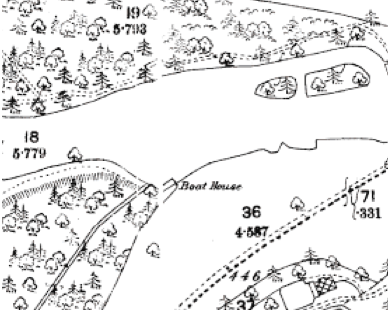

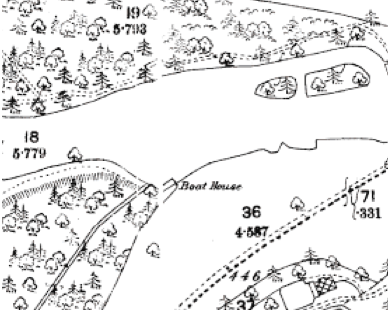

Fig. 10 Outline plan from 1885 OS map

Fig. 10 Outline plan from 1885 OS map

Settlement Remains

The village appears linear in form, but if the nineteenth-century

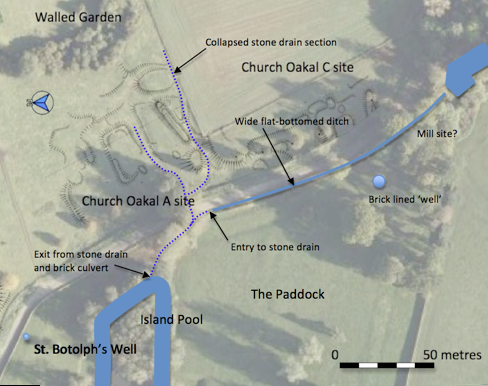

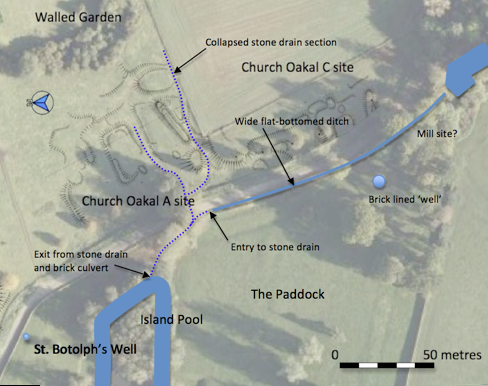

developments to the north are discounted and the earthworks to the south are factored in, we have a more nuclear plan centred on the church (Fig. 10).The earthworks in Church Oakal field (Fig. 11) had not previously been surveyed in detail. The field occupies the north side and bottom of a shallow valley which lies between two hills; Oakal Hill to the south and Church Hill to the north. Today some of the field is occupied by the remains of the early nineteenth-century walled garden. Church Oakal C site has the remains of some small-scale quarrying.

Church Oakal B Site.

Here four distinct platforms may be identified and interpreted as a farmstead with the main house on the crest of the hill on the western side of the complex (Fig. 7) and a larger building, possibly a barn, to the east and smaller ancillary buildings to the north. Alternatively, there could have been up to four individual dwellings. This area is bounded on the north by the churchyard wall acting as a revetment to the higher ground around the church. The suggestion that these buildings may have been removed to improve the view of the church from the Game Larder (Fig. 71) is confirmed by the discovery of early eighteenth-century pottery in the destruction rubble spread across part of the site (Wass 2012a). To the west of the platform complex is an obvious holloway, which runs down the hillside from a point east of the church to the Banbury road, where it curves round to join the existing roadway. On the other side of the park wall is St. Botolph's Well and it seems likely that the holloway linked the church to the holy well (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11 Earthworks in Church Oakal Field.

Church Oakal A Site

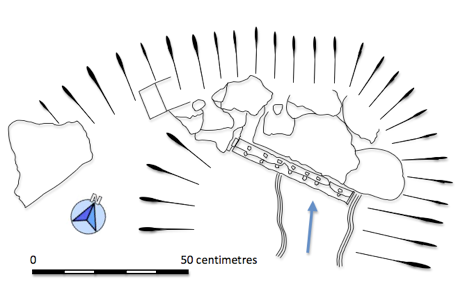

The valley bottom has a series of earthworks in varying states of preservation (Figs. 11 and 12). The most prominent feature is a bank running roughly east-west parallel to and a little upslope from the valley bottom. The bank merges into the valley side at its east end where it is cut by two deep channels. It has been leveled towards its west end and terminates above a marshy area just short of the road. Interpretation is difficult because of the destruction by ploughing of further earthworks in the field to the south. Stone work is eroding out from the southern margin of the bank towards its western end.

Fig. 12 Church Oakal A site, from north (Photo CM).

Central to the site is a rectangular platform with a raised rim and a shallow moat. To the north-west the moat broadens out into a low level area marking the site of an attached fishpond. Other banks and terraces suggest the possibility of ancillary structures in what appears to be a typical medieval homestead site, possibly the remains of the manor. Recent excavations uncovered a stone revetment on the south bank of the platform and an internal sleeper wall (Fig. 13) indicating the presence of a timber-framed building associated with late-medieval pottery (Wass 2012b) .

Fig. 13 Church Oakal A site, revetment to moat and sleeper wall, from east (Photo VW).

The Fishponds

Fishponds attest to the importance of fish in the medieval village economy (Aston 1988). Steane emphasizes that fishponds, ’were not a seigniorial monopoly; villagers as well as manorial households drew fish from them’ (1984:172). However, more recent studies have questioned the practical and economic efficacy of some fishponds and have indicated the possibility of more ornamental functions within landscapes designed to reflect the power of elites (Liddiard 2005:107). Many fishponds have been recognised as post-medieval design features and of limited value as commercial fisheries (Aston 1985: 60). Structures described as fishponds may have performed other functions: watering livestock, habitat for wild fowl, mill ponds and even retting ponds for the processing of flax and hemp (Geary et al 2005). This complicates our understanding of those fishponds at Farnborough which are possibly pre-eighteenth century.

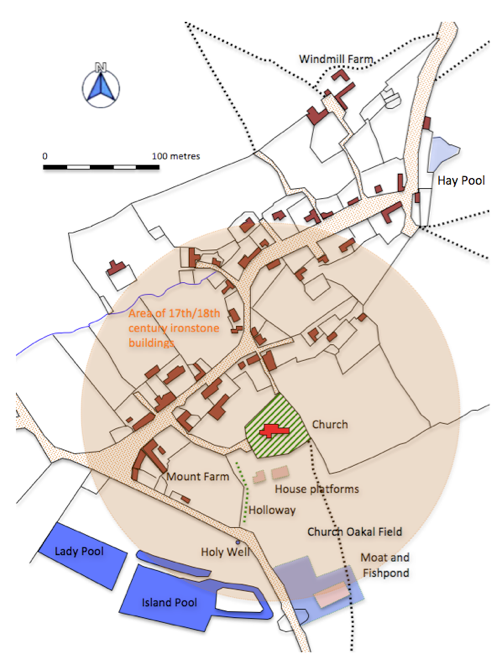

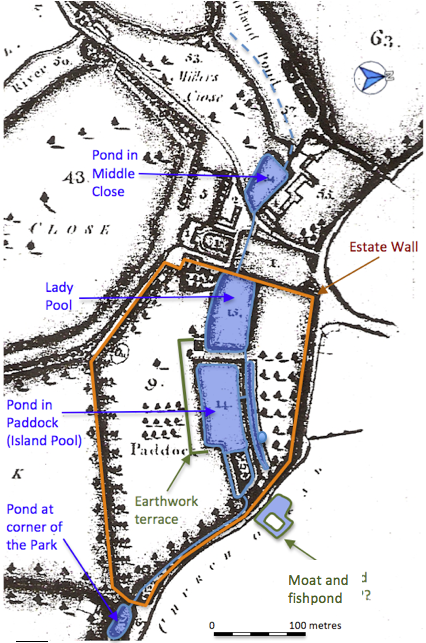

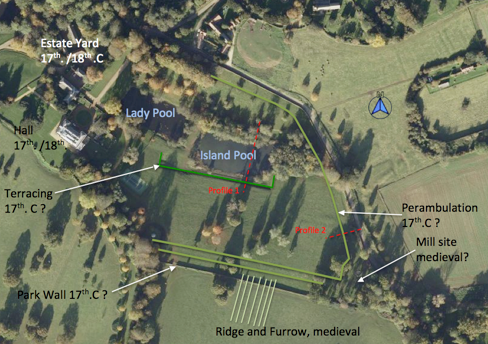

Fig. 14 Fishponds south of church, 1772 map

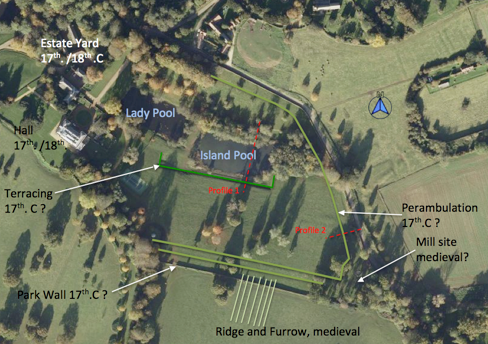

Four ponds are recorded on an important estate map of 1772 (Linnell) running in an arc to the south of the church. From east to west these were labeled as the Pond at the Corner of the Park, the Pond in the Paddock (now the Island Pool), the Lady Pool and the Pond in Middle Close (Fig. 14). Upcast on the banks indicate that the first of these has recently been cleared by mechanical excavator potentially changing its size and shape. Today it is roughly rectangular and is fed by a culvert under the road from an adjacent pool which is not on the 1772 map and signals an attempt to clear marshy ground around a natural spring. Earthworks suggest that this pool originally supplied water to a small mill to the west.

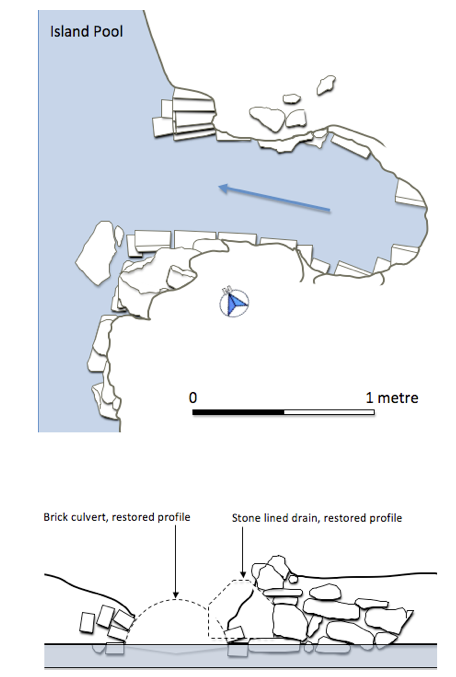

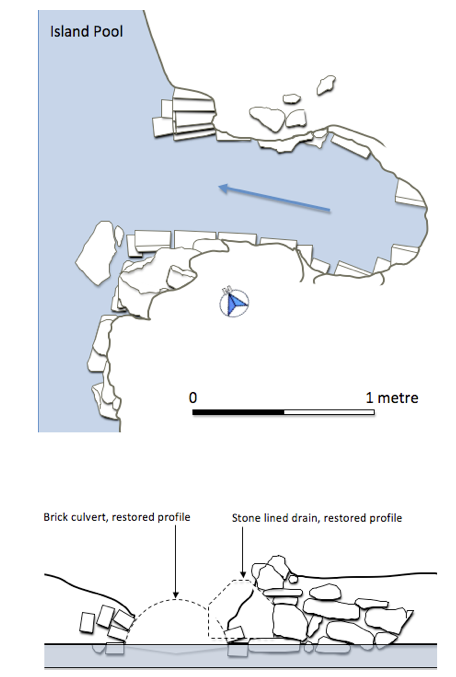

It is possible that a series of fishponds continued down the valley to the west, however, it seems likely, given their central location within the later park, that each of these was heavily re-modeled in the post-medieval period. The Island Pool in particular may have started as a smaller medieval fishpond, been enlarged in the seventeenth century to create a stew pond and then further improved in the eighteenth century by the addition of a narrow curving water course that defined an island at its east end.

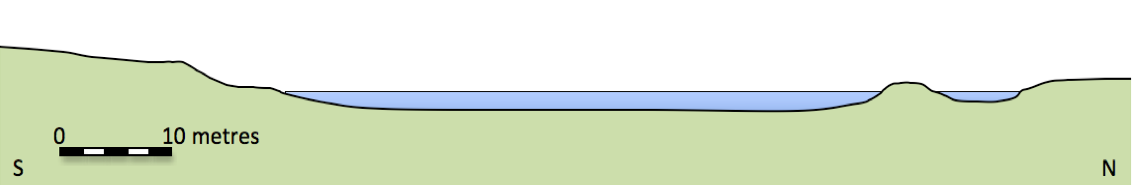

The Island Pool’s southern limit is marked by a terrace nearly 2 metres high, although there has clearly been silting along this side reducing the pool’s overall width by around 4 metres. To the north is a further long thin pond running parallel to it and separated from it by a low bank (Fig. 15). The bank is pierced at a single point to unite the pools. Some decayed brickwork at the northern end of this channel indicates the presence of a sluice gate. The function of the narrow pool is again problematic. The most likely purpose of the complex was to manage the creation and harvesting of fish stocks. In medieval terms the large pool would be for breeding, the vivarium, and the linear pool would be for holding fish, the servatorium, before removing the available catch by sweeping a net along its length (Currie 1990:22).

Fig. 15 The Island Pool, profile 1.

The water is held in place by a broad earth dam (Fig. 16) and is drained from the western end of the linear pond through a brick lined culvert into the Lady Pool. The slightly smaller Lady Pool is rectangular and in turn is drained through a sluice gate which leads into a culvert running underneath the lawn, the estate yard and ultimately into Sourland Pond.

Fig. 16 Dam between Island Pool and Lady Pool, from south (Photo VW).

In 1772 there was another body of water, the Pool in Middle Close. This was filled in possibly during early nineteenth-century work on the estate, however, a low retaining dam survives which defined its eastern end (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17 Dam for Pool in Middle Close, from north.

A further focus of interest lies to the north of the village in a small valley running east-west (Fig. 8). The field here, named in the 1772 survey as Great Pool Close, is today laid down to pasture. However, there are some interesting indications of the presence of a ‘great pool’. Towards the north-west side of the field and along its north-east and south-east margins is a well marked terrace around 1.5 metres high which roughly follows the 140 metre contour. The natural lie of the land causes a considerable narrowing of the valley towards the southern corner of the field where there is a low earth bank, now broken through, and an adjacent level platform which could be the site of a building (Fig. 18). The limit of the pool is also demonstrated by the termination of a well preserved set of ridge and furrow (Fig. 19), evidence for the pool being medieval in origin. Other potential early pool sites include Little Pool Close, marked on the 1772 map a couple of fields over to the north. A small rectangular pond can be seen here, although it is much eroded by livestock drinking from it. Ordnance Survey maps up to 1972 show the triangular Hay Pool at the north end of the village (Fig. 10) but this has since been built over.

Fig. 18 Great Pool Close, from south.

Fig. 19 Great Pool Close, aerial view.

The Mill Sites

Although none were recorded at Domesday one might expect water mills to feature in the village economy. Three potential sites have been identified as pre-dating the emparkment, none of them particularly large. It is unlikely that they would have been operating at the same time with shifting locations reflecting changes in technology or economy.

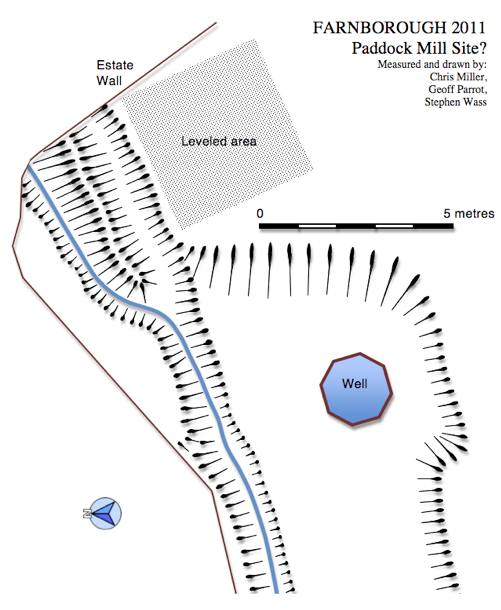

The first potential site is in the Paddock (Fig. 20). An earthwork consisting of two parallel channels emerges from the pool further east. On the south side of these channels is an obvious leveled terrace which may be the site of a mill building (Fig 21). One could envisage a wheel across the southern most channel with the northern one acting as a bypass. Any original mechanisms for controlling the water would have been swept away when the estate wall was built, possibly in the 1620s and by a later farm track. There are some traces of stone work, particularly on the bank dividing the channels.

Fig. 20 Mill site in the Paddock, bypass channel left, building platform right, from west (Photo VW).

Fig. 21 Mill site in the Paddock, plan.

The second site is at the southern end of the Great Pool (Figs. 18 and 19). This would have been the largest body of water in the medieval landscape and the combination of dam with adjoining building platform must be significant.

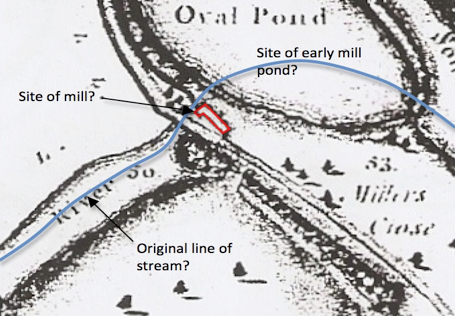

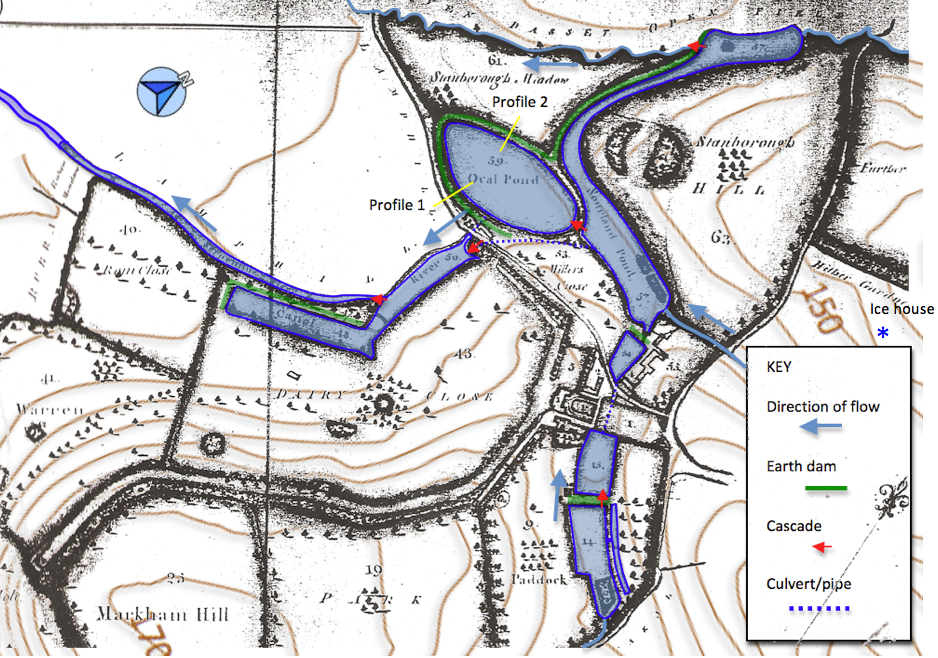

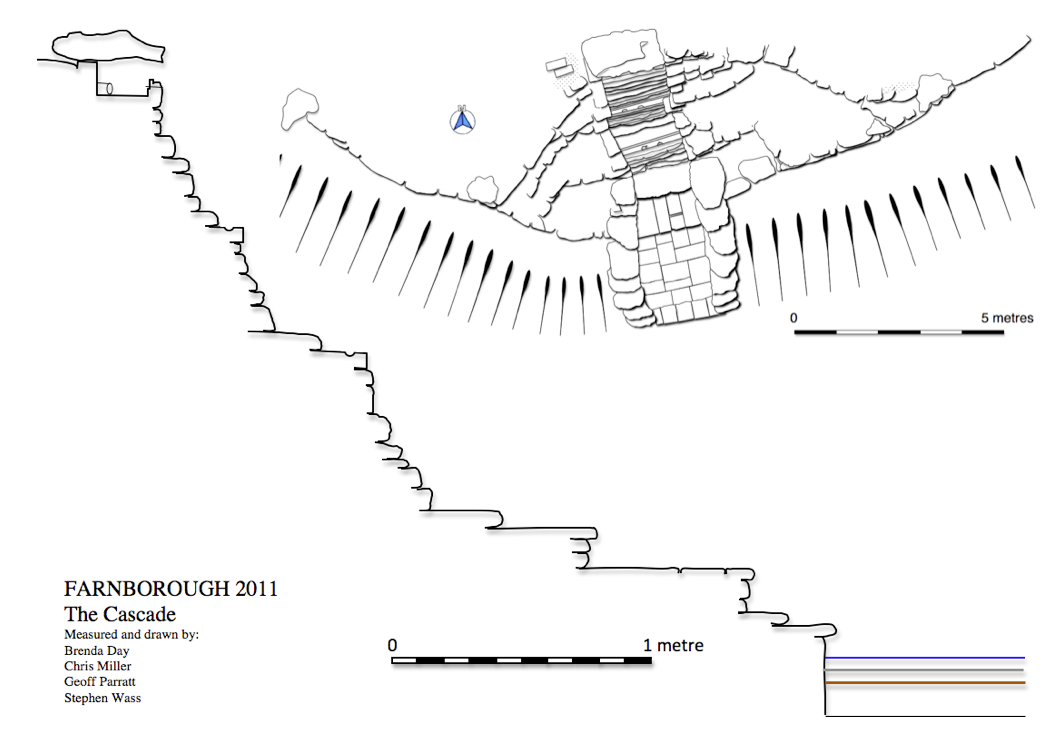

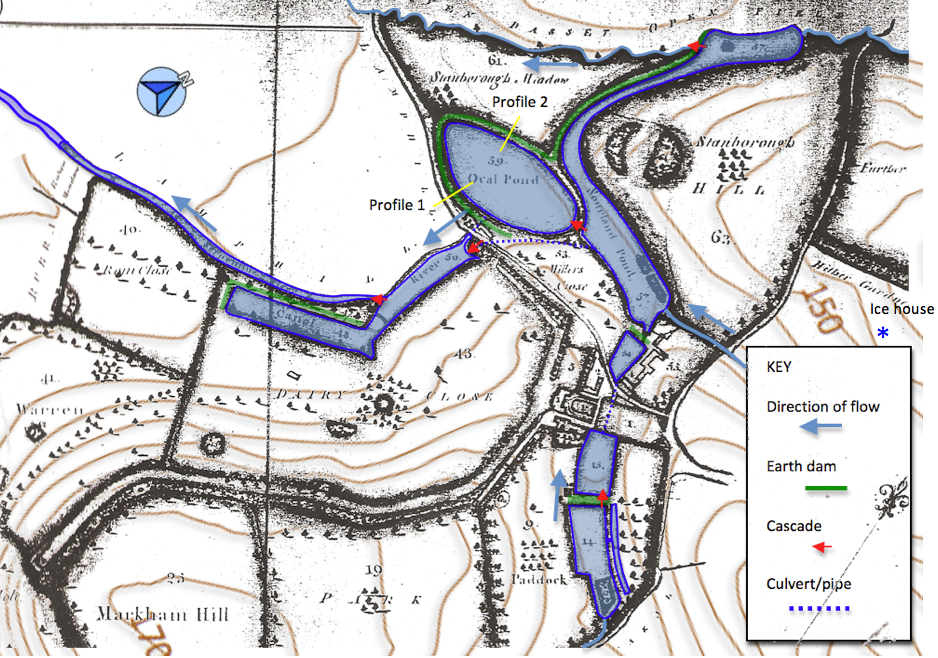

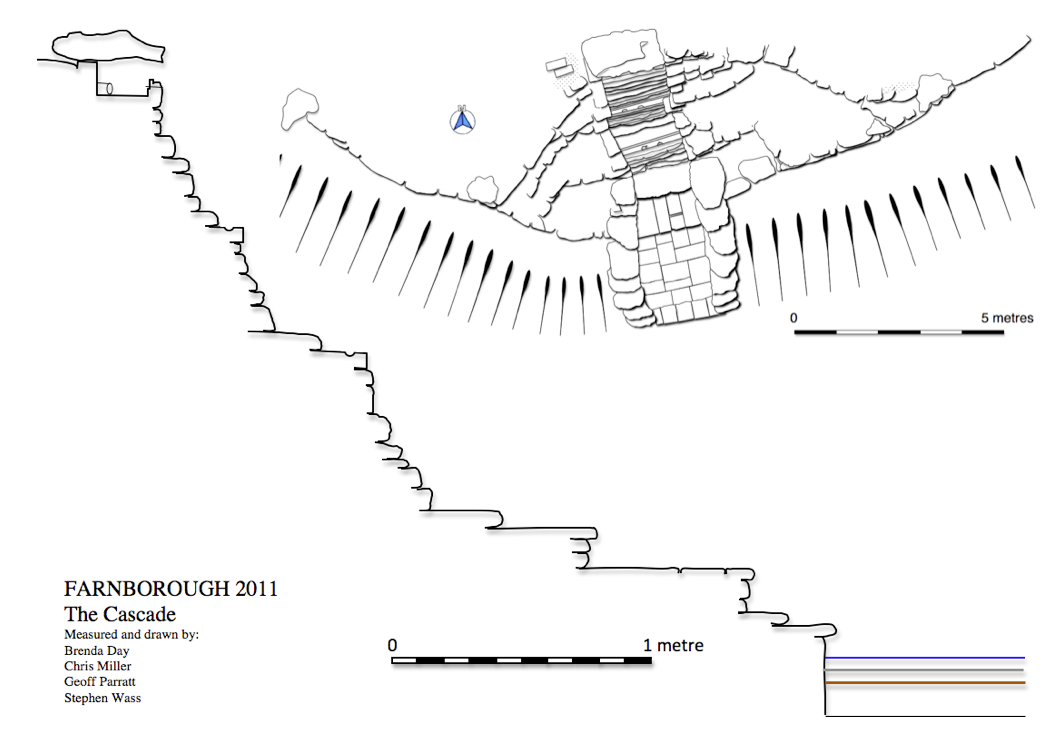

The final area of interest lies to the west of the hall. For some time the Holbech family maintained that the eighteenth-century cascade was built on the site of a mill (Meir 2006: 91). The adjacent meadow is named Millers Close on the 1772 map but when a detailed survey of the cascade was undertaken there was no evidence for the reuse of an earlier structure (Wass 2011a). What was clear, following a closer examination of the map (Fig. 22), was that there was a small ‘L’ shaped building to the north. Given its position, immediately next to the outflow from the eighteenth-century Oval Pond, it is possible that this was the earlier mill site. Examination of the ground today reveals the scattered stone foundations of a small building (Fig. 23).

Fig. 22 Area around Cascade, 1772 estate map.

Fig. 23 Stone foundations of ‘L’ shaped building, from west.

In

considering these potential mill sites it should be noted that it would

be possible for the entire mill to have been of timber frame

construction (Astill 1993), as we can illustrate with ethnographic

parallels today (Fig. 24). The use of water power in the middle

ages, whilst essential to the local economy, may have been based on

quite ephemeral structures.

Fig. 24 Water mill, early twentieth century, Astra Museum, Sibiu, Romania.

Discussion

The early use of water at Farnborough is reflected in fishponds and mill ponds. The community would depend on these for food (Fig. 25) and power. We also get hints of other functions: defensive as in the case of the moat and spiritual as evidenced by St. Botolph’s Well. The essential nature of water is undeniable, what is harder to grasp is what this resource actually meant to the community. The conventional picture of resource use mediated by the manorial authorities may fall short with respect to the interest that the peasantry had as stakeholders. In terms of capital investment the chief land holders would pay for the construction of mills and ponds to generate income, but the position of those who worked the land was perhaps, as Dyer (2009: 183) suggests, more nuanced: ‘The peasant economy contains paradoxes. Peasants produced for the market, yet practiced self-sufficiency; they made technical innovations, while continuing with many traditional practices; they were consumers, but on a modest scale… the final paradox of the peasantry concerns the collective nature of their agriculture, while they retained a high degree of individual autonomy’. This suggests a greater degree of independence in thought and deed than is generally recognised and opens up the possibility that there was a sense of shared ownership of water resources even though technically they remained in the possession of the local lord.

Fig. 25 Angling, 14th century wall painting, Horley, Oxfordshire.

The manor was securely in the grip of the Ralegh family by the mid-fifteenth century. In the early-seventeenth century Sir George Ralegh enclosed 200 acres of land by re-grouping estates through mutual consent (Salzman 1949: 84). This early instance of enclosure may have been the occasion for the demolition of some buildings in Church Oakal as it was noted that this resulted in the loss of 13 houses. At the same time a specific area was set aside for a park in what was later called The Paddock (Fig. 30).

The Paddock is the only large enclosure which is completely walled. Where the wall runs alongside the lane from Banbury it is of stone with an elaborate moulded capping (Fig. 33). Although this has been largely rebuilt in modern times the point remains that it is a high status construction which presents an impressive face to the public highway. The lane, crossing the valley on an embankment up to 2 metres high that is retained by the estate wall, may have also been constructed in the early-seventeenth century as it cuts across the medieval earthworks. The wall which forms the southern margin of the Paddock is brick over lower courses of stone (Fig. 26) and can be seen on aerial photographs cutting across ridge and furrow (Fig. 30). This is another well built structure with two offsets defined by courses of moulded brickwork.

Dating bricks from appearance alone is difficult (Bailiff 2007: 828). However, the small size, colour range and degree of erosion certainly appears seventeenth century when compared with better dated examples such as those that may be seen at Chesterton (1630s) and Packwood (1650s) both in Warwickshire.

The ponds have already been discussed in detail (pages 11 to 13) and although possibly medieval in origin they seem to have been remodeled to become the focus for the Jacobean Park.

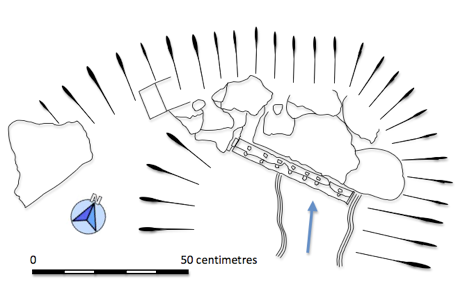

The hypothesis that this small park was created in the early-seventeenth century and supplanted medieval arrangements gains further support by considering the drainage patterns. A series of stone lined drains take water out of the site of the former moat and attached fishpond and empty into the top end of the Island Pool (Fig. 27). These drains are characterised by the rough quality of the work but are fully lined in stone and at one point an entry is protected by iron bars (Fig. 28). At the outlet point into the pool the stone drain is obviously cut by the insertion of a later eighteenth-century brick lined culvert (Fig. 29). The culvert is set at a lower level indicating that further efforts were made to improve the drainage of the land to the east and suggesting an earlier date for the stone drain.

The final features which, if not precisely dating the creation of the park, signal its special status, are the earthworks which give additional definition to the perimeter on all sides, except the west, where the landscape has been altered by developments in the mid-eighteenth century. The presence of viewing terraces over-looking Jacobean gardens is well documented (Currie 2005:14). The terraces and shallow ditches here define a circuit of the park that could have been walked, ridden or driven, in short a perambulation. This can be paralleled at nearby Wormleighton, Warwickshire, where medieval fishponds had, by 1632, been adapted to form the centre piece of a small wooded park (Mowl and James 2011: 39) whose margins were similarly defined by an earthwork which shadowed the boundary (Fig. 32). The perimeter earthworks at Farnborough (Fig. 30 and 31) may reflect the later eighteenth-century practice of defining the margins of the fields with double rows of trees as depicted on the estate map (Fig. 14), however, whilst this was widespread throughout the park, nowhere else shows the terracing seen in the Paddock.

The hall’s earliest architectural features are on the west front which probably dates from around 1700. Some thick internal walls indicate the possibility of an earlier house encased in the eighteenth-century construction (Haworth 1999: 16). A large pile of stonework behind the estate yard derives from the demolition of the service wing in the 1930s (Haworth 1999: 19). This shows evidence for a stone building of massive construction with stone mullions that would not be out of place on a major building of the early seventeenth century. Enclosures of the early 1600s could have gone hand in hand with the removal of the hall from its previous moated site to the rather drier location to the west, with improved prospects in both senses of the word.

Discussion

This analysis of the creation of the seventeenth-century park is largely based on conjecture, drawing together the facts about enclosure and the topographical evidence. However, if we accept this development as likely a number of consequences followed on for the locals. The turmoil occasioned by early enclosure is well documented and commented on. In many cases the attractions of sheep farming lead the drive to early enclosure. At Wormleighton the Spencer family had five shepherds looking after 10,000 sheep (Stocker 2006:82) partly on land formerly part of the village. Although peasant uprisings were not common, 45 outbreaks of rioting were recorded in England between 1585 and 1660 (Walter and Wrightson 1976: 26). There were a series of anti-enclosure riots known as the Midland Rising of 1607 which ended in a pitched battle at Newton in Rockingham Forest. During the course of this around 1,000 Levellers were driven off and some 50 dispatched on the spot. These instances of ‘rebellions of the belly’ (Hindle 2003: 137) occasionally resulted in direct attacks on the grand houses.

We have no indication of any unrest at Farnborough, but it is difficult to imagine that radical changes went unremarked. The customary patterns of rights, duties and obligations linked to usage of mills and fishponds must have been subject to change following the creation of the park. Of further significance was the exclusion of the community from access to St. Botolph’s Well (Fig. 33). The arrangement of church, holy well and connecting thoroughfare was probably an ancient one which reflected the communal use of this spring for practical and spiritual purposes. What is striking today about the spatial relationship is that the seventeenth-century park wall cuts across the bottom of the former route and effectively restricts access to the well as it is now on private property.

A door in the wall, which by analogy to other local properties, appears to be eighteenth century (Wood-Jones 1963), was provided to allow some access. This door could only be opened from the park side. Even allowing for the fact that the Reformation brought about a divorce between the established church and the idolatrous practice of visiting a holy well one must assume that on some level of superstition the well still occupied an important part in the community’s consciousness. What was communal has become private.

The Holbech family belonged to that category of English landowners often described as country gentry, members of a broad spread of second ranking elite, below the comparatively small number of peers but above the numerous ranks of those engaged in trade (Cannon 1987:10). The Holbechs would find themselves somewhere within the spectrum described by Corfield (1996: 4) ‘At the upper end of the scale, the gentry included the younger branches of the nobility… at the lower end of the scale, the status of the lesser gentlemen tailed away into the ranks of the substantial freeholders or yeomanry’.

There are some problems in writing an historical outline of the Holbechs of Farnborough. All four major published accounts are essentially the same (Nares 1954, Haworth 1999. Meir 2006 and Ince 2011) and refer back ultimately to ‘family tradition’. Holdings in the Warwickshire County Record Office include several boxes of papers including: surveys and plans (WCROL1); estate and household accounts for 1813-94 and a scrapbook containing miscellaneous correspondence (WCROCR 656); and estate and household accounts for the years 1771-1782, 1791-1796,1810-1812 (WCROCR 1799). Valuable as these are for understanding subsequent management of the estate, they offer no coverage of the crucial years when the park was under development.

The family originated in Lincolnshire but moved to Fillongley, Warwickshire in the fifteenth century and rose to prominence within the county over the next two hundred years. Ambrose Holbech (1596 – 1662) settled in Mollington, a parish adjacent to Farnborough, in 1629. His son, also named Ambrose, became a lawyer who, according to his monument in Mollington Church was, ’very eminent in ye Law… which he practiced with great integrity’. He clearly had some influential contacts, marrying his daughter Sarah to Sir Thomas Powys who became solicitor-general in 1686. In 1684 Ambrose purchased the estate at Farnborough from the executors of the Ralegh family. Nares (1954) notes that the estate was ’much encumbered’ and that only £2,260 out of the total purchase price of £8,700 was paid, the remainder having been advanced by Ambrose as a mortgage on the property. Work on the house and grounds was begun by Ambrose’s son William who in 1692 married an heiress, Elizabeth Alington, but it was their son William, who succeeded his father in 1717, who was responsible for the main changes (Ince 2011: 85 to 88).

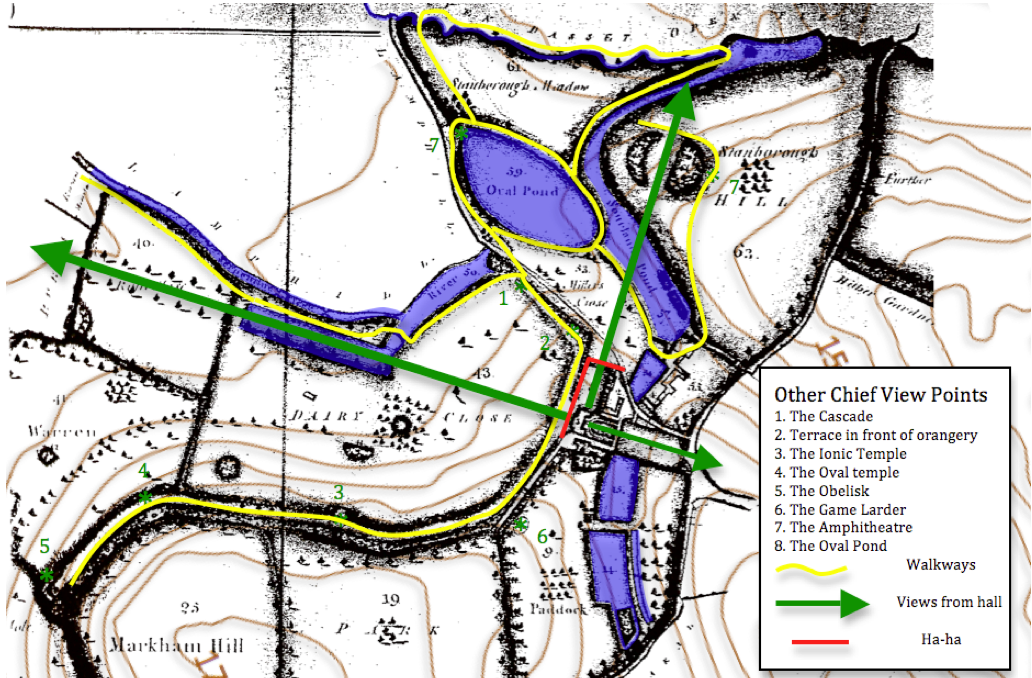

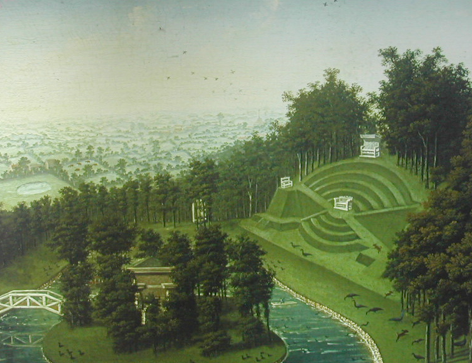

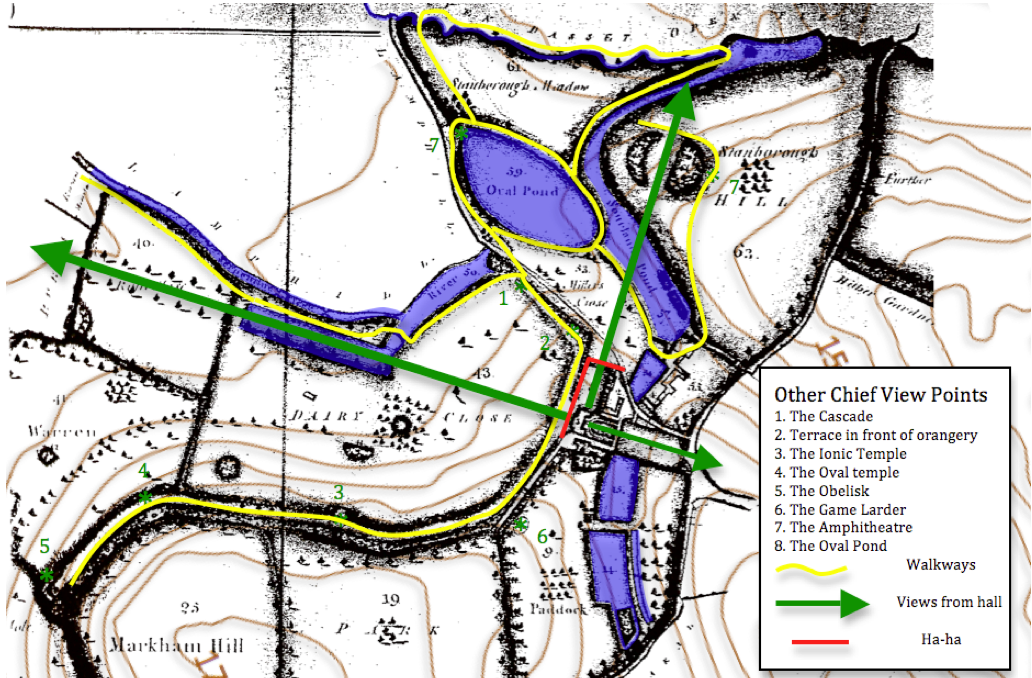

The family tell the story that William was ‘disappointed in love’ and around 1724 he departed for Italy, where he lived for over a decade. Upon his return he brought with him paintings and classical sculptures which established his reputation as a connoisseur. Early in the 1740s work began on remodeling the house and park with a strong emphasis on the classical. In the house paintings by Canaletto and Panini were hung amidst elaborate Rococo plasterwork (Fig. 35). About the park no less than four buildings were erected in the classical style. These were associated with the construction of a huge terraced walk running south from the hall (Fig. 39) and were: the Game Larder (Fig. 92), the Ionic Temple (Fig. 38), the Oval Temple (Fig. 40) and the Pentagonal Temple, now lost beneath a nineteenth-century cistern. In addition an obelisk (Fig. 34) was stationed at the end of the terrace walk completed in 1751. William never married and continued to supervise his estate until his death in 1771.

His nephew, also named William, took over the house and garden and one of his first acts was to commission a detailed survey of the property by Edward Linnell ( Linnell 1772). This consists of a series of detailed maps, often of individual fields and is of enormous value in understanding the work carried out earlier in the century. William died in 1812 and the property was inherited by another William ( 1774 – 1856). The new incumbent was responsible for developing the estate in association with the architect Henry Hakewill (English Heritage 2011). A further lengthy period ensued until the house and park passed to William’s third son Charles (1816 – 1901) in 1856. Charles took holy orders, became archdeacon of Coventry and, as well as spending large amounts of money on restoring the church, also built a new road that linked the village with Avon Dassett to the north-west. In 1901 the inheritance passed to his grandson William (1882 – 1914) who died during the First World war whilst serving with the Scots Guards. His brother Ronald (1887 – 1956) took the property on and it should have passed to his son Edward (1917 – 1945) but he died in an accident on VJ day. Subsequently a settlement was made and Geoffrey (1919 - ), Edward’s brother, inherited the estate. Much of it was sold off in 1948 following damage by serious gales in the previous year and in 1960 the remaining property, including several residences in the village, passed to the National Trust in lieu of death duties.

Discussion

A number of key questions remain unanswered by the historic record, most notably queries linked to the work done by the Holbechs towards the end of the seventeenth and into the eighteenth century. First amongst these is how was it planned and what did it cost? We also need to understand how the work was carried out. Further questions relate to how the park was used and ultimately, what was its purpose? In the absence of relevant documentation we will need to turn to the archaeology of the park for partial answers to some of the questions, as they relate to the use and management of water resources.

Studies of period gardens have mainly taken an art-historical approach and our understanding of the technology employed in these landscapes remains limited (Roberts 2001: 12). In order to examine the construction of the eighteenth-century water features we will make use of contemporary manuals and the limited number of archaeological investigations on related structures.

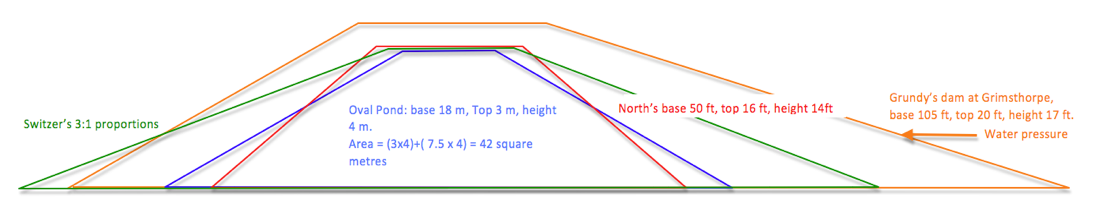

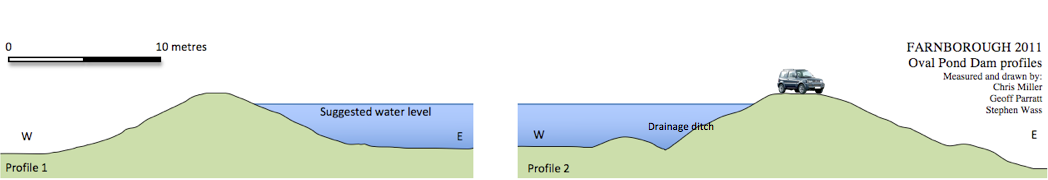

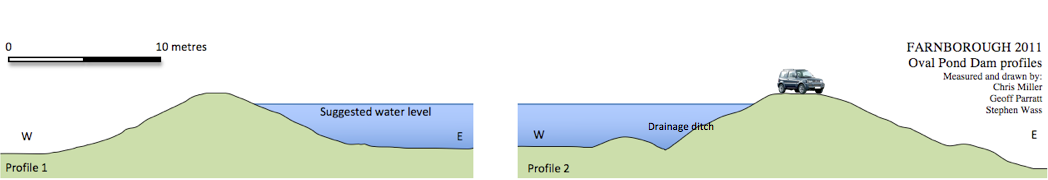

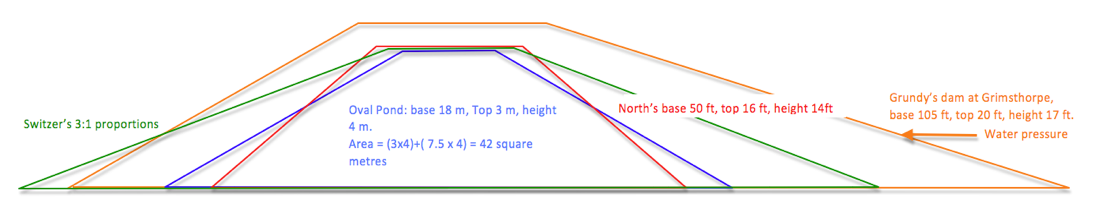

Ponds and Dams

The garden designer and engineer Stephen Switzer (1734:128) felt it was easy: ‘With us… every ploughman and shepherd is able to make good reservoirs or ponds for holding of water’ and gave clear directions as to proportions: ‘three foot horizontal to one foot perpendicular’ and materials: ‘large spits of clay together just as they are dug out of the pit, only picking out the large stones, or any veins of sand you can find therein… then you are to throw some slaked lime over it’ (Switzer 1734:131). Roger North (1714: 5), ‘a person of honour’, writing two decades earlier gave similar advice as to materials and in particular the importance of, ‘good ramming, from a foot or so below the surface of the ground to such height as you propose the water shall stand’. His sizing for a middling pond indicates that for a dam 14 foot high at the centre one must, ’make your bank at the foot at least 50 foot wide, straightening by equal degrees on either side bring it up to 16 at the top’. North (1714: 15) was also very specific about the demands made on labour, ‘take the assistance of your neighbours and provide yourself with six tumbrels, four good horses and two stout labourers, besides a driver to each pair of tumbrels. I call them pairs because they work alternatively with the same horses so that one is filling, while the other is moving and your labourers as well as horses are always at work’. North (1714: 17) later recommends upping the labour force to twelve which should be adequate so that by, ‘observing these directions you may make two ponds in one month and not expend in money above 80 pounds although you pay for every hours work of man and horse’.

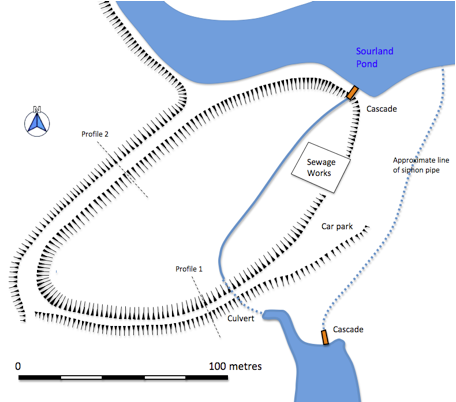

It is interesting to compare this forecast with other work that has been done on sites such as the experimental earthwork on Overton Down where labourers, using basic technology on hard chalk, could shift around 0.15 cubic metres per person per hour (Jewell 1963: 51). More material than this could be dug, but that demanded two other labourers moving and piling the spoil. A more recent set of figures comes from advice issued by the University of Sterling Institute of Aquaculture (2012) who, in giving guidance in reservoir construction for the tropics, suggest that for digging and moving earth by hand one cubic metre a day is reasonable whilst those spreading and compacting could handle two cubic metres. We can appreciate the scale of the work at Farnborough if we consider the dam of the Oval Pond. This amounts to around 10, 500 cubic metres of earth and would give North’s twelve stout labourers over 875 cubic metres each to shift, around three years’ work. If they wanted to complete the job in a summer season between planting and harvest, say 100 days, they would need to employ roughly 100 workers a day. Given that the entire male population of Farnborough in 1821 was 179 (Warwick CRO DR299/16) it is easy to see why North’s advice to call on neighbours for assistance was so apposite. Not all members of the gentry would take on such a project on a ‘do-it-yourself’ basis and it is possible that a professional engineer was employed at Farnborough such as John Grundy of Spalding (1719 to 1783) whose experience came from work on drainage and flood defence in East Anglia.

He was employed at Grimsthorpe Hall, Lincolnshire from 1745 to create the Great Water, a project for which his notebooks survive (Roberts 2001). Grundy’s work was generally considered to be of high quality and more technically accomplished than that of his competitors

(Roberts 2001: 18) and his cross valley dam at Grimsthorpe, whilst a little higher, is considerably wider than those at Farnborough (Fig. 73). Even so he was compelled to return in 1758 and 1774 to make repairs. His use of additional timber piling and a further clay lining (Roberts 2001: 24) recalls the situation at Noke, Herefordshire where the excavation of an early eighteenth-century dam revealed wooden stakes set in clay (Currie and Rushton 2001: 230). The dams at Farnborough are largely grassed over and there have been no opportunities to examine any internal structure.

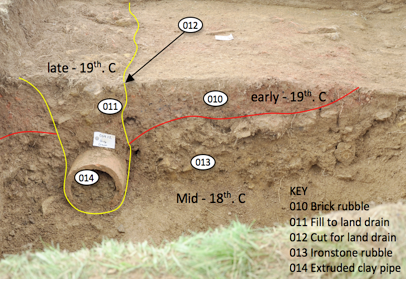

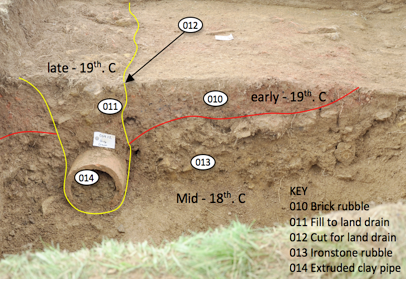

Drains

Contemporary writers stressed the importance of a dependable supply of water and enormous pains were taken to ensure this, including the provision of subsidiary reservoirs around springs and on occasions pumps operated by animals or waterwheels (Roberts 2001: 22). It seems that at Farnborough the existing springs and streams were adequate for the task and, together with the drainage of the surrounding meadows, provided sufficient water. The complex pattern of drainage around the former manor site has already been noted (pages 20 to 21). Recent excavations have shown that prior to the nineteenth century a large quantity of ironstone quarrying debris was dumped in the moat to partially fill it and no doubt improve drainage (Wass 2012a). Brick lined culverts have been recorded emptying into the Island Pool and running below the dam of the Oval Pond. In addition a curious set of broad shallow drainage ditches have been noted, following the field boundaries on the estate map and running straight down the hill below the terrace (Fig. 74).

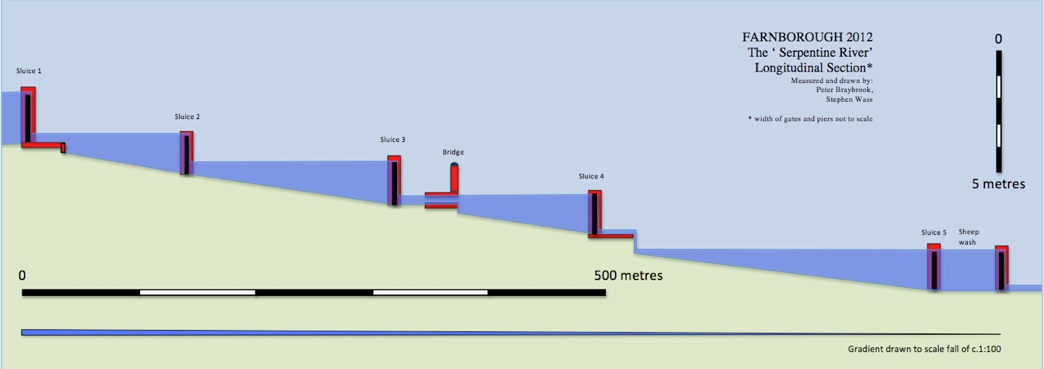

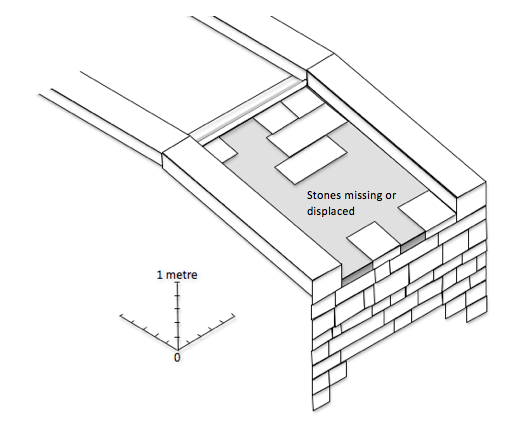

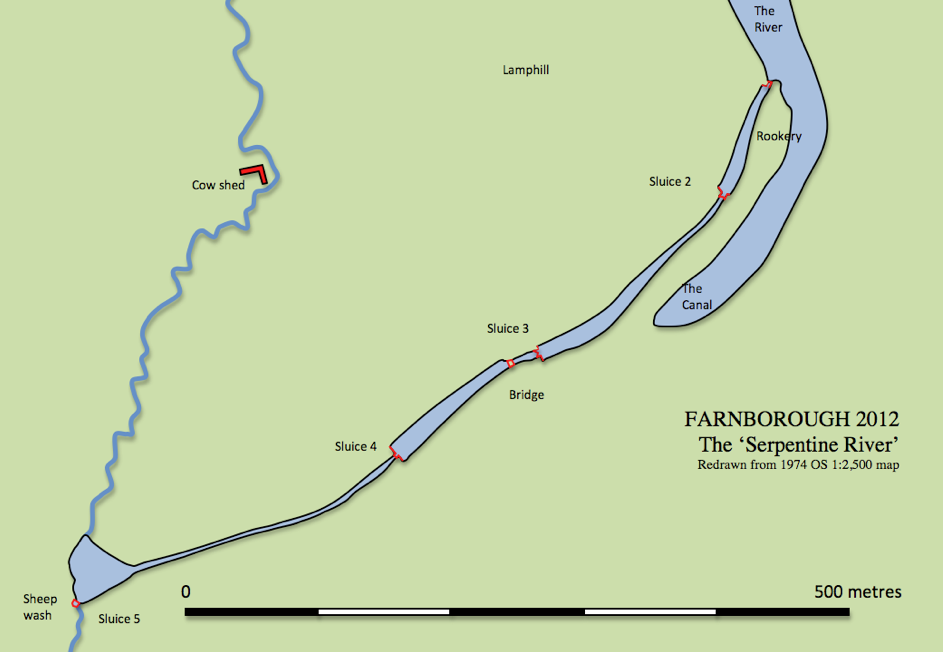

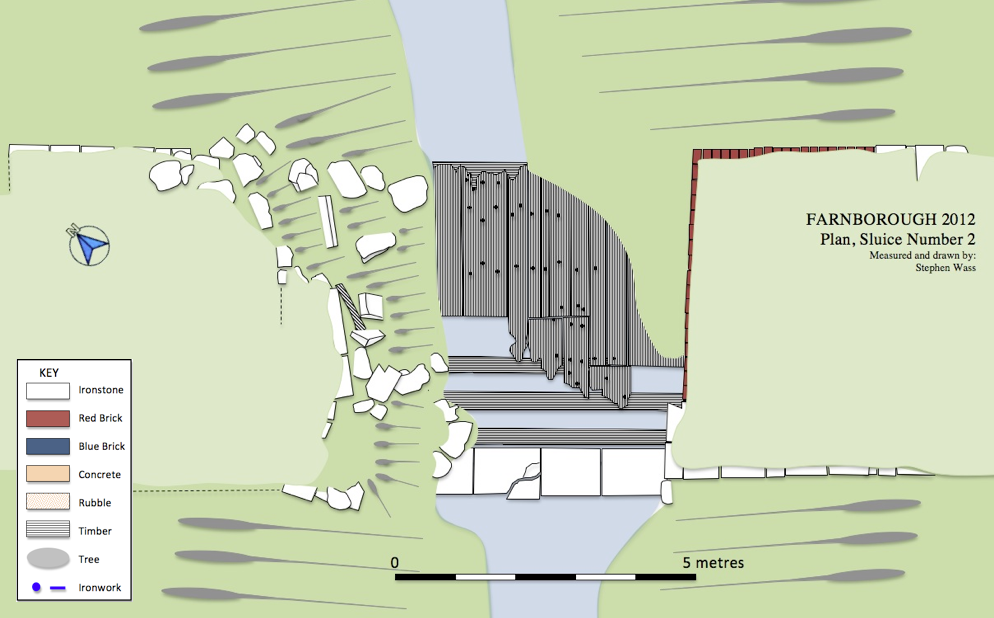

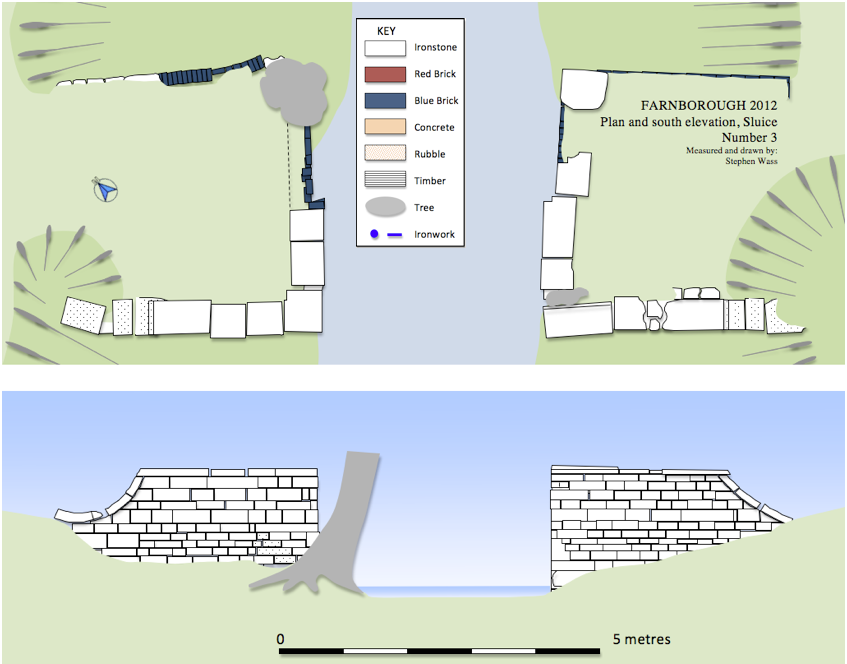

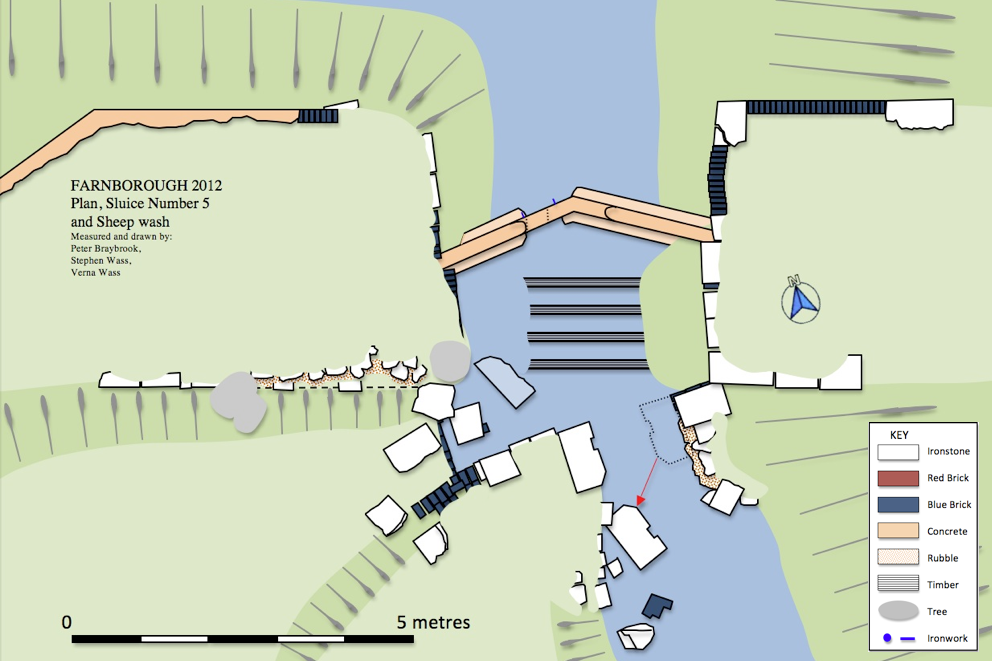

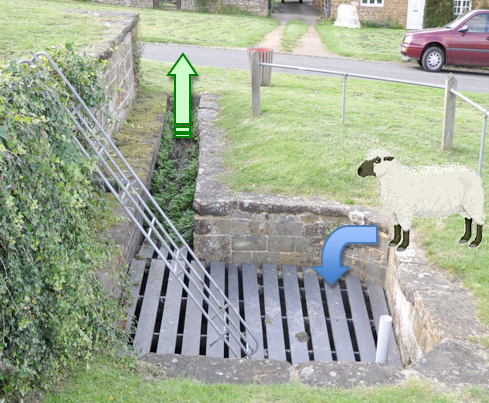

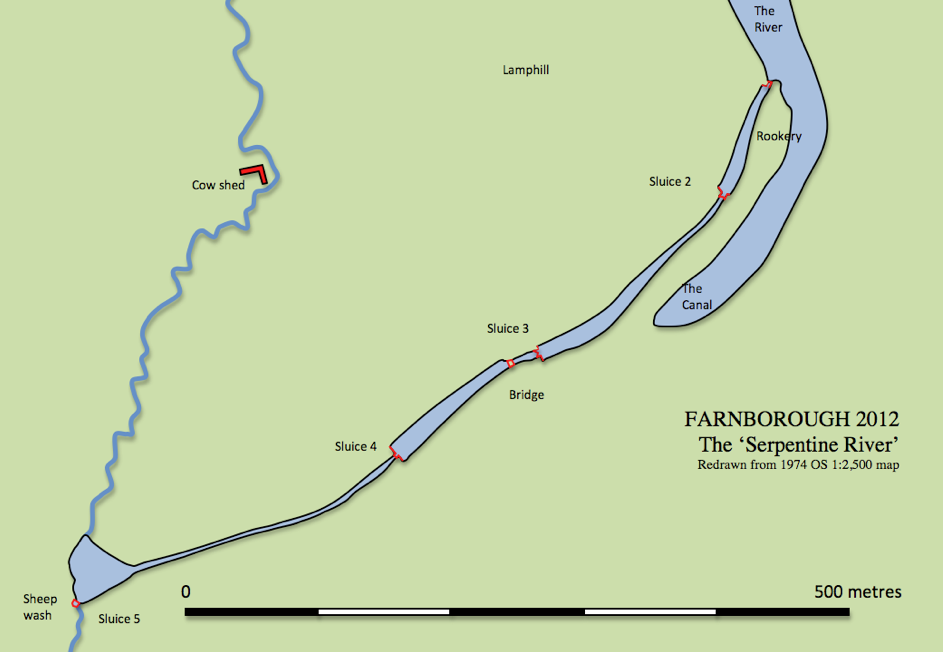

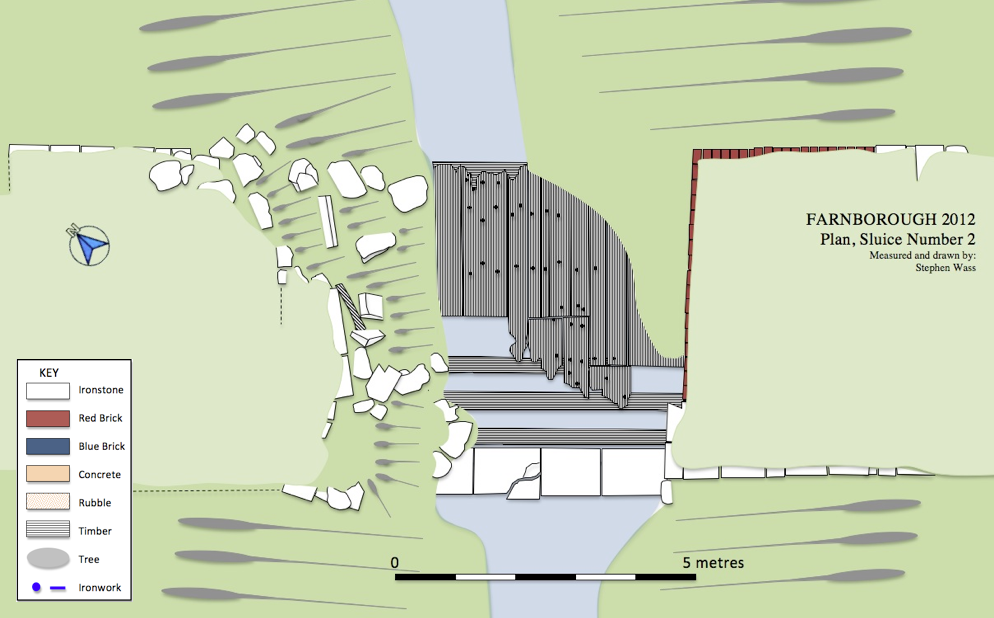

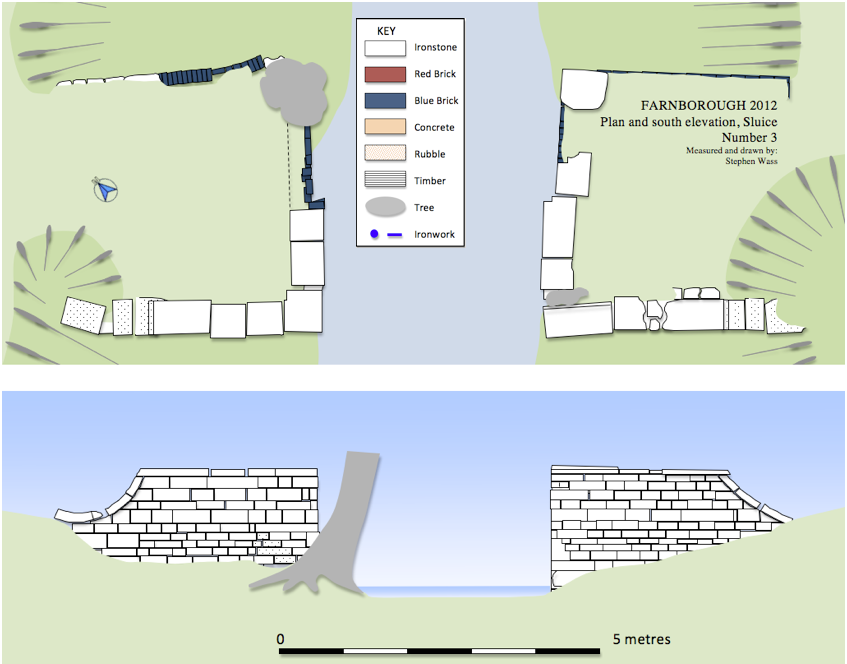

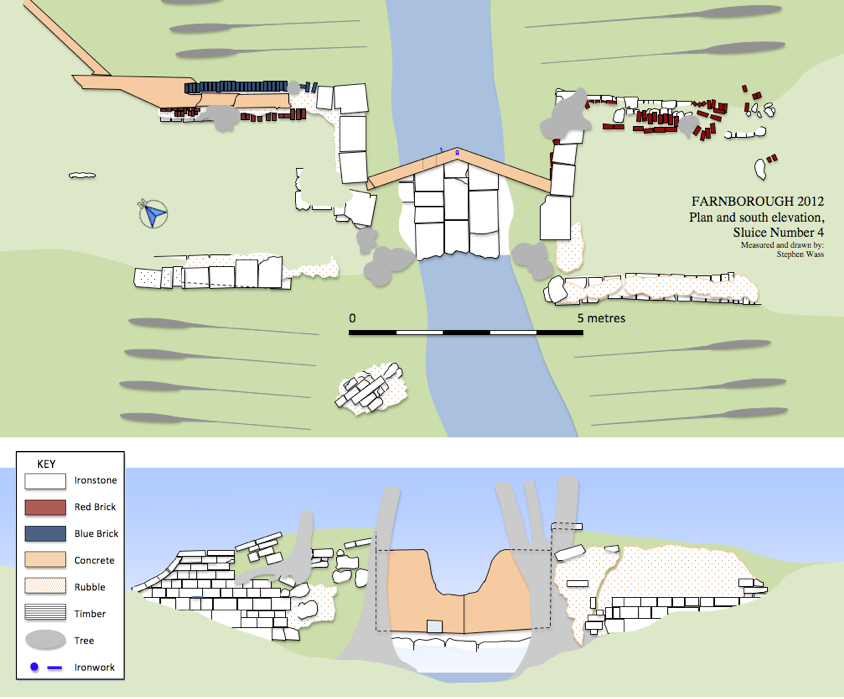

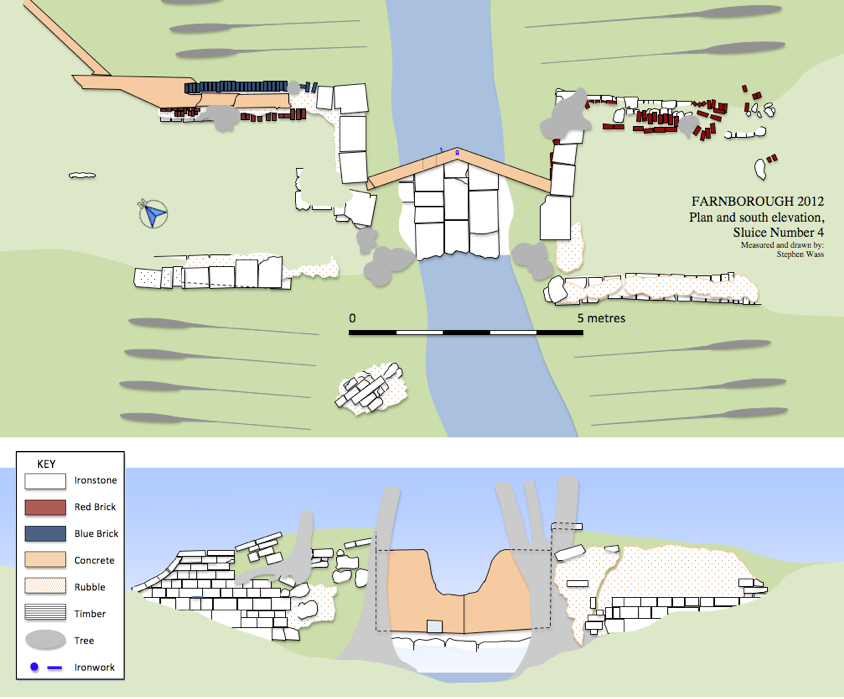

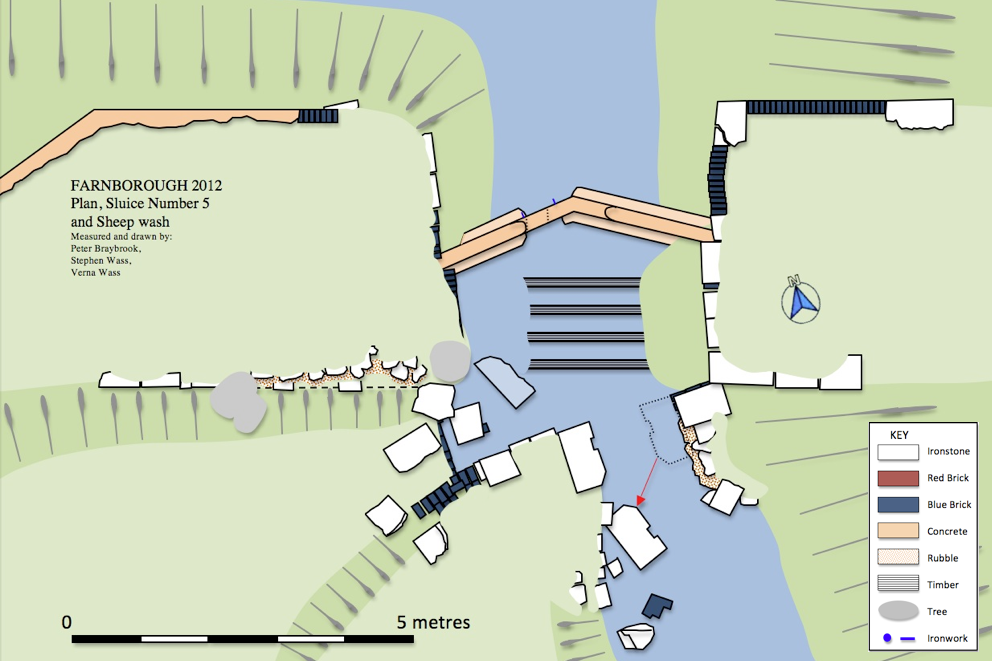

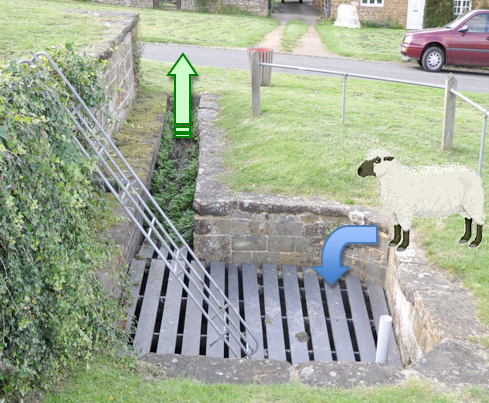

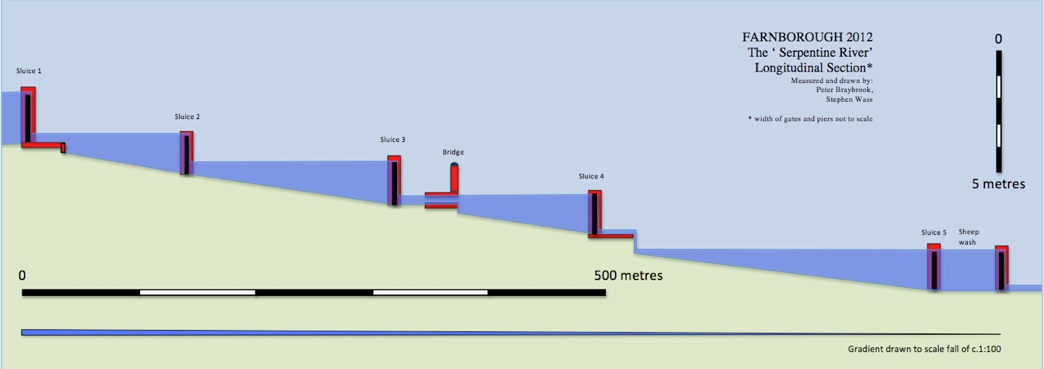

Sluices

The most refined technical accomplishments are the sluices along the Serpentine River. Currie (1990: 35) notes that, ‘in all the treatises examined there is very little recorded about sluices’, perhaps because they were regarded as the province of specialized craftsmen. Usually the term sluice describes an arrangement for draining a pond through a pipe or culvert, often of wood, that passed below or round the dam. Control was usually by wooden paddle or bung (Roberts 2001:22). The sluices at Farnborough are much more reminiscent of staunch or flash locks, features associated with early canal and river navigation. These operated on the principle of a pair of mitre gates which retained the water at a suitable level for navigation. Approaching boats were held back while a small sluice was opened to drop the water level a little and then the gates were opened to allow the boats to slip through. Such locks (Fig. 75) were used from the earliest times and were still reasonably common in England in the first half of the eighteenth century until they were replaced with the more familiar pound locks (Hadfield 1968: 19). Was the Serpentine River navigable? A similar visual effect could have been achieved by more conventional earth dams, so the sluices must have been installed with some functionality in mind, however, there is no evidence that the stream beyond was ever adapted for boats.

Projecting the water levels back from the presumed height of the gates gives an indication of the relative water heights and demonstrates that the cascade below sluice 4 would have been visible even when sluice 5 was closed (Fig. 76). Could Holbech have employed contractors whose experience on early canals led them to build the only way they knew, or were the sluices designed simply to demonstrate the technology? Would the arrangement have helped if there was ever a need to drain the water-course in a hurry? The whole question of the use of sluices on the Serpentine River remains open, but the conjecture is that they had some purpose other than the ornamental.

Finance

North promised that one could deliver a lake of between three and four acres for eighty pounds. Given that most of the raw materials would have been available on the estate the main cost would have been for labour at as little as a shilling a day (Porter 1991: vii). If a specialist supervisor had been appointed on the same basis that Grundy worked he would have charged one shilling for each pound of the project’s cost (5%). Money would need to be set aside for both carpenters and stone masons to work on sluices and cascades. These higher paid artisans may also have been available as employees of the estate, but would have commanded higher wages than the labourers, as much as five shillings a day. Taking all this into account we might expect the work on the Oval Pond to have cost in the region of £600. A further attempt at costing can be made on the basis of sums paid out during the construction of the Wiltshire and Berkshire Canal in 1797, where 31/2 d per cubic metre was paid for digging and 11/2 d for carting (Lawton 2006: 300). On this basis the earthworks alone could have cost around £300. Similar calculations for the other water features suggest an overall bill for Farnborough between £2,500 and £3,000. This compares with an estimate for £1,250 2s 1d from Grundy for a major expansion to the Great Water at Grimthorpe (Roberts 2001: 28)

There is one near contemporary account of the workers’ efforts, penned by a local curate, Richard Jago, who was a friend of Miller’s.

Alas we must in all probability ascribe the work force of five hundred and their merry countenances to poetic licence and there is no mention of their wages.

Williamson (1999: 252) suggests that, ‘Once we have reconstructed the layout and appearance of early landscapes we must… try to recreate the ways in which they would have been perceived and experienced from various spatial standpoints by the different social actors moving within (or excluded from) them’. This is not the place to enumerate every conceivable way in which people and water could have interacted but rather to focus on those aspects which have left significant remnants in the landscape. No doubt occupants of the hall made copious use of water for drinking, cooking and washing, however, as the service block which contained a dairy, brewhouse and kitchen was demolished in the 1930s there are few traces. It is worth noting the presence of an icehouse to the west of the hall (figs. 42 and 77) which made use of the seasonal freezing of pools (Buxbaum 2008). Workers would have chopped out blocks of ice in the winter to provide ice for the kitchens in the summer.

In order to populate the eighteenth-century landscape we will need to turn to other contemporary documents including paintings. Being aware of the dangers of projection and the assumptions one makes about the ‘familiarity of the past’ (Tarlow 2004) , one can attempt to gain insights by appealing to common human impulses which are shared today by workers in the park and visitors to it. The ponds and waterways were a place of work to those who laboured on the estate and of leisure for the Holbechs and their guests. It is interesting that it remains the case that most accounts still present an upstairs rather than a downstairs perspective of the country estate.

Fig. 77 Icehouse entrance, from south-west. Fig. 78 Scrubbing algae off the Cascade (Photo CM).

Work

In working with water, the local labourers would have had a role both in construction and maintenance. Tasks, which are shared by the modern work force, included periodic dredging of pools as they silted up, repairs to banks damaged by livestock and unblocking and repairing sluices. Observations on the cascade have shown that in summer the stonework becomes covered with unsightly brown algae which needs to be removed by hard scrubbing every couple of weeks (Fig. 78).

It seems likely that the pools were managed for fish into the eighteenth century, a complex business involving transferring stocks from pool to pool, feeding, the periodic emptying of pools for cleaning and, of course, harvesting and preparing the fish for the table (North 1714: Chapters XI to XVIII). Even with every modern aid working around water is a cold and dirty business, how much more so in the eighteenth century. We have no documentation relating to these processes at Farnborough, as is the case generally, the voice of the eighteenth-century labourer remains silent. The fact that it is easier to say many more interesting things about the recreational uses of water is perhaps a simple reflection of the cultural hegemony enjoyed by the social elite.

Leisure

North (1714:73) is particularly strong on the recreational benefits that accrue to a gentleman’s family as a result of embracing water, ‘Young people love angling extremely; then there is a boat, which gives pleasure enough in summer, frequent fishing with nets, the very making of nets, seeing the waters, much discourse of them, and the fish, especially upon your great sweeps, and the strange surprises that will happen in numbers and bigness, with many other incident entertainments, are the result of waters, and direct the minds of a numerous family to terminate in something not inconvenient, and it maybe divert them from worse’. The view by Rysbrack (Fig. 72) also neatly encapsulates the recreational opportunities afforded by water. We see a couple promenading by the water, gentlemen angling from a boat and a flight of ducks available for wild-fowling, a pattern repeated in many similar genre paintings from the eighteenth century.

Walking.

Contemporary documents such as Miller’s own diary entry for July 21st. 1750 emphasise the importance of walking within the context of living well, ‘Lord North and Miss Legge breakfasted at castle. Went with Lord Cobham etc. to Mr. Holbech and to Dassett. Mr. Holbech dined with us. Camera Obscura. Walked with Lord Cobham, Holbech and Miss Banks round Wood Close, fountain etc. Supped at castle with Lord North etc. and Holbech. Fine evening. Music. Lord Cobham’s venison’ (Hawkes 2005: 150). The presence of water would enhance the experience of walking to all the senses, ‘when the shadows grow faint as they lengthen: when a little rustling of birds in the spray, the leaping of the fish, and the fragrancy of the woodbine, denote the approach of evening’(Whately 1770: 86). These experiences were not only confined to the owner and friends. There were opportunities for members of the public, albeit of the better sort, to make visits, often on carefully designed designated walks around an estate (Symes and Haynes 2010: 22). Although we have no indication that this happened as a matter of course at Farnborough, it is clear that other members of the gentry were made welcome and given the chance to tour the gardens (Meir 2006: 87).

Boating.

We have no evidence of boating in the eighteenth century at Farnborough. Although a boathouse is shown on the 1885 OS map on Sourland Pond (Fig. 79) it does not appear on the 1772 map, however, it is hard to believe that boats were not present here. Miller had designed a boathouse (Fig. 80) for Enville in Staffordshire (Meir 2006: 151) and would have been well acquainted with the extensive use of boats on the lakes at Stowe, Buckinghamshire (Felus 2006: 26). Lady Newdigate who visited Farnborough in 1747 might have expected to see boats. She wrote in her Journal of another location, 'in a small boat we rowed to the Severn and then in a very pretty vessel built by Mr. Cambridge, the Cabin lined with Japan and Indian paintings we sailed for several hours, the view all the way very pleasant' (WCRO CR1841/7: 53).

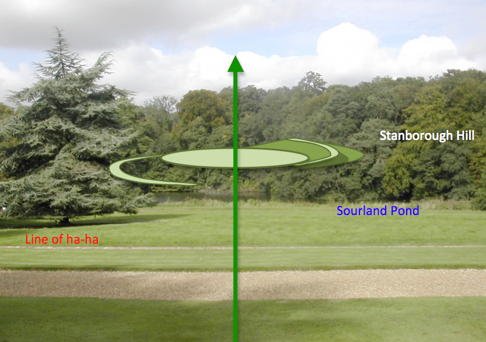

Sourland Pond seems an ideal venue for boating as its pronounced curve around Stanborough Hill would have given a feel for a great journey in a small space. Felus (2006: 30) also mentions the naumachia or mock naval battle, inspired by classical precedents and indulged in by the Byrons at Newstead, Nottinghamshire and the Dashwoods at West Wycombe, Buckinghamshire. Is it too fanciful to note that the Oval Pond shares very closely in the proportions and size of the floodable area of the Colosseum in Rome? This is not to say that William Holbech filled it with battling galleys but perhaps there was an echo of this famous monument somewhere in the back of his mind.

Angling.

The layout of the pools at Farnborough was well suited to the maintenance of fish stocks on a large scale and whilst fish could be caught by netting they would also offer the opportunity for the pastime of angling. Anglers appear in many eighteenth-century prints and paintings and a large number of books on the subject were published during the period (Rodd 1846: 84) attesting to its popularity as a sport for gentlemen and indeed ladies. Fishing pavilions known from Enville, Staffordshire ( Fig. 80) and Kedleston, Derbyshire reinforce this picture, but again, save for the existence of the ponds, we have no direct evidence for angling at Farnborough.

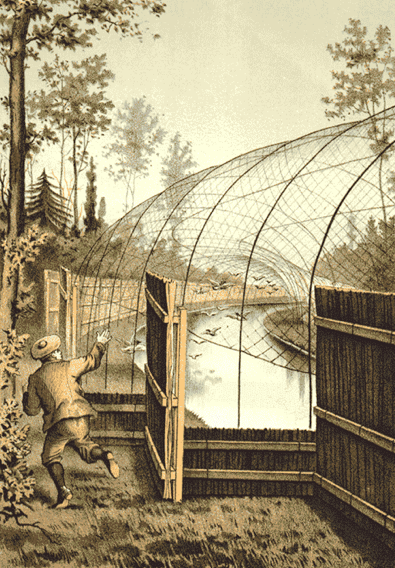

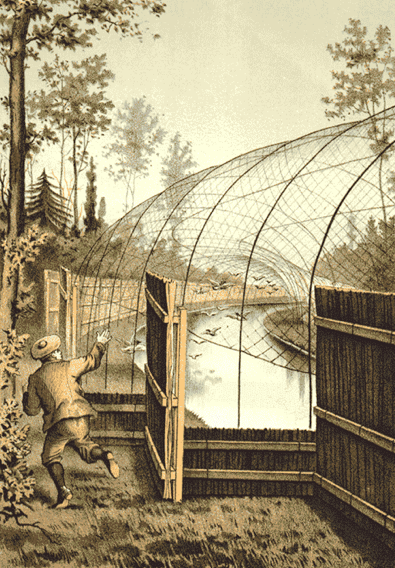

Wild-Fowling

Another sport which gained popularity through the eighteenth century as firearms became more reliable and readily available was the hunting of wild fowl. It has been suggested that the island at the eastern end of the Island Pool with its narrow looping channel could have served as a duck decoy. This is unlikely as the normal form was to have lengths of water of diminishing width, opening off from a central pool (Heaton 2001). These were netted over and the birds lured or driven in to them (Fig. 81). It is more reasonable to assume that the island was created as a refuge for wild fowl, where they could roost and nest in safety from predators. The presence of the game Larder shows how important hunting was on the estate (Fig. 92).

Swimming

Of all the activities noted so far, swimming seems to be the one least likely to leave archaeological traces. It is hard to see today’s muddy, overgrown stretches of water, choked with fallen trees, as anything but a health hazard (Fig. 82) , however, when newly built with firm banks and pebble bottoms one could envisage features such as the Oval Pond or the Canal being appropriate venues for swimming. One possible indication that we have of interest in this activity is a document preserved in a Holbech family scrapbook from the mid-eighteenth century (WCRO CR656/36). Amongst newspaper cuttings for a variety of sports ranging from prize-fighting to horse-racing is an engraved handbill publicizing the opening of Peerless Pool in London in 1743. For a guinea a year gentlemen could enjoy all the benefits of swimming in a safe environment with ‘waiters’ on hand to teach swimming to novices. The accompanying illustration not only shows swimmers in action but also a couple of adjacent ponds for angling and two large prospect mounds joined by a terrace ‘planted with limes’. If nothing else it is an indication of the kinds of cultural influences that could have been operating on Holbech during the crucial decade in the park’s transformation.

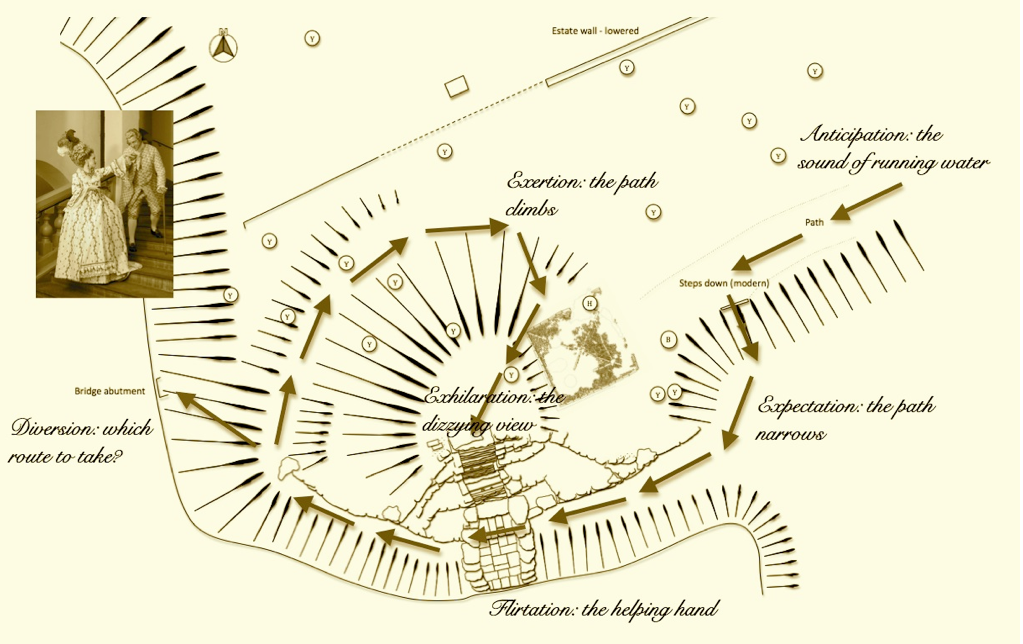

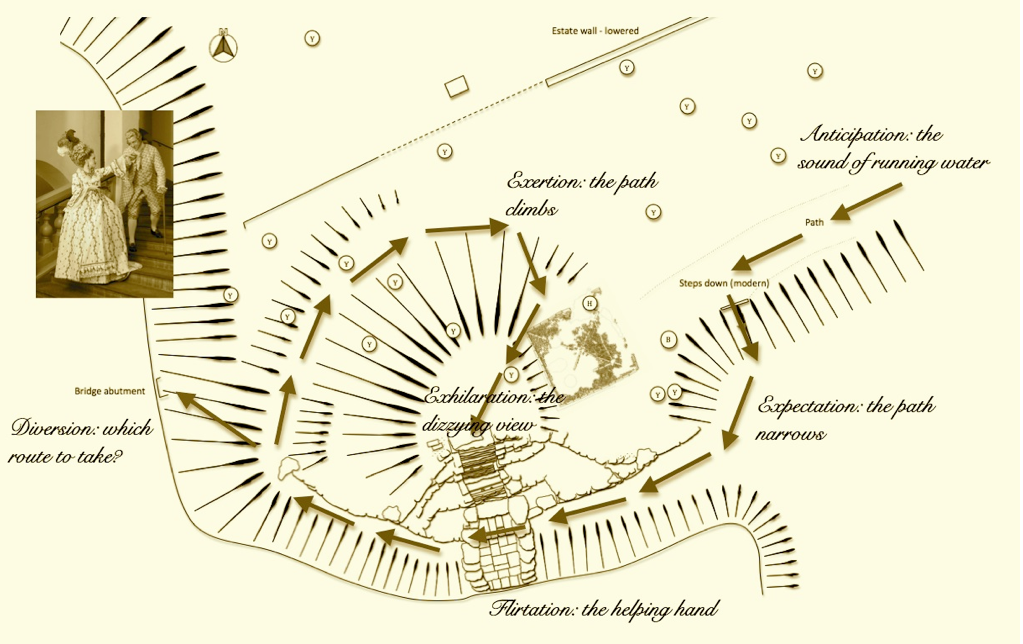

Experiencing the Cascade

Our final imaginative leap is to attempt to draw on even less tangible elements of the past and recreate one potential way in which a water based construct could have been experienced in the eighteenth century. This idea was developed in an earlier piece (Wass 2011c) where we noted the lack of visibility on the approach to the Cascade implying an element of discovery and anticipation for the visitor. The structure of the Cascade (Fig. 50) seems to draw one into experiencing it in very particular ways which include walking across the flat slabs at the base of the flow (Fig. 83) and striking out along a spiral path to attain the summit with its view along the River (Fig 51).

This led to the creation of a slightly tongue-in-cheek visitor’s guide (Fig. 84). Other sites where, ‘garden features… were designed to trick, tease or thrill the visitor’ have been listed (Wass 2011c: 16), including the hidden fountains at Wilton House which were ‘… like a plash’d Fence, whereby sometimes faire ladies cannot fence the crossing, flashing and dashing their smooth soft and tender thighs and knees by a sudden inclosing them in it’ (Quoted in Strong 1997: 130). This kind of titillation may have been better suited to earlier centuries or warmer climes (Thacker 1970: 20), but we must allow for the possibility of an eighteenth-century sense of fun.

Discussion

One is very aware of the contrasts between the two different ways in which people experience water around the park. On the one hand the labourers responsible for its upkeep were likely to be task oriented and motivated by the simple mechanics of providing for themselves and their families. Their options were limited and their focus on getting the job done in the best way they knew. On the other hand there are the gentry who had so many more options to choose from. It was even possible to write poetry; in 1786 M. Dawes published an octavo volume entitled ‘Holbeach Fish-pond, a Poem’ (Rodd 1846: 84), unfortunately we have not been able to discover a copy.

It is important not to fall into a narrative which features, ‘contests between hapless peasants and villainous landlords’ (Tarlow 2007:10) and accept Williamson’s (1999: 253) point that, ‘eighteenth-century England was a complex society and not one composed of two confronting groups’, however, it is difficult to think about a feature like the Oval Pond without considering dichotomies. Walking out towards Meir’s (2006: 91) ‘bastion’ at the far end of the pond one would be confronted with an astonishing prospect. To the right the large elevated expanse of water, perhaps with pleasure craft upon it, to the left and decidedly below, a bleak landscape of labour consisting largely of the still open fields belonging to adjacent villages (Linnell 1772).

A structure such as the Oval Pond cannot be seen as anything other than domineering, it pushes out across flat fields and imposes leisure upon labour (Fig. 85). We do not know how this construction was viewed at the time, indeed all the labourers may have continued to be ‘jocund’, relieved to have a steady wage from employment on the estate. Even so there is no sense in which this was a community enterprise, rather it represents a transformation effected by two gentlemen with their own particular and peculiar interests. One cannot believe that such a transformation was met with equanimity by the rest of the population.

This narrative could be abandoned at the point where water usage is at its most extravagant but to do so would be like leaving off a biography without pondering the subject’s final years and possible extinction. By the early-nineteenth century the estate was in something of a decline. In 1810 a curious poem was posted anonymously to Charles Holbech, brother of the William who had inherited in 1771. The poem is entitled ‘The Lamentation of the Botanic Gardens at Farnborough’ (WCRO CR656/36) and appears to be a plea that the gardens be put in order so that, ‘no more shall urtica (nettle) eclipse the rose’, and ‘ no supple juncus (rush) with incessant bow, court the green mantle of the stagnant lake’. In 1812 another William took on the estate and by 1815 a further major programme of work was underway supervised by the architect Henry Hakewill (English Heritage 2011). The estate was put on a more productive footing and new buildings included cowsheds (Wass 2012d) and a large octagonal walled garden with a stone lined pool at its centre (Fig. 86). A graveled path led from the garden, through a short tunnel, to another path across the Paddock and up to the kitchens. The moat was further filled with brick rubble and, post-1850, large clay land drains were inserted (Wass 2012a), demonstrating the continuing importance of effective drainage (Fig 87).

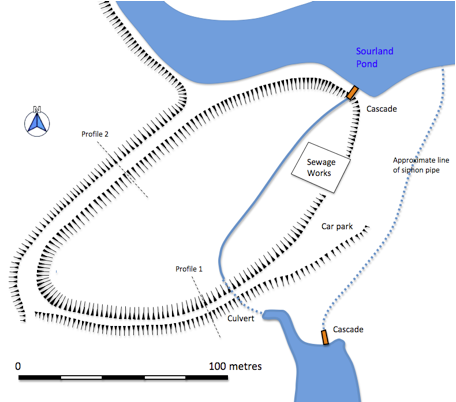

In the early-nineteenth century a summerhouse (Fig. 88) was built on a terrace cut into the mound at the back of the Cascade and a wooden footbridge on brick piers (Fig. 89) thrown across the inlet to the River (Wass 2011b). This post-dates the building of a new road to Avon Dassett by Charles Holbech. The Oval Pond was drained between 1820 and 1880 and typically for the period was converted in a fox covert (Watkins, N. 2007).

The kitchen garden was abandoned shortly after the First World War and was for a while worked as an independent market garden until it closed in the 1950s. The hall had had its own water supply from a borehole on the top of the hill to the south-east sunk in the first half of the twentieth century. The water was pumped up by a windmill and stored in a brick cistern before being piped to the hall. In 1957 mains water came to Farnborough and shortly afterwards a sewage works was built on the edge of the former Oval Pond (Fig. 90).

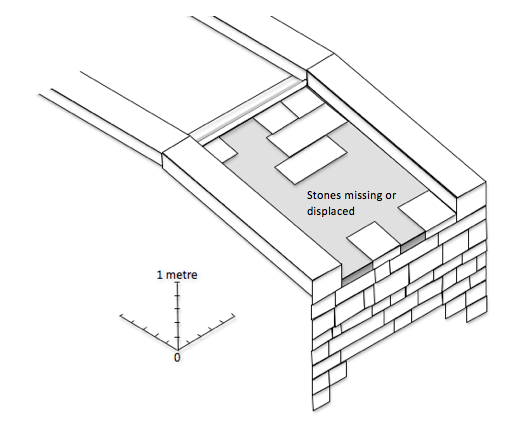

The Serpentine River was drained after the Second World War and in 1960 the National Trust took over guardianship of that portion of the park which had not been sold in 1948. Today the residents of the hall stock the pool with wild-fowl over winter for shooting and operate a small rowing boat on the River for retrieving downed birds. Sourland Pond is let out to the Banbury and District Angling Association and in the summer people come and picnic on the grass next to it. The grounds close to the hall are managed by a gardener and a part time assistant, whilst the remaining agricultural land is let out to a tenant farmer. The decades since the Second World War have not been kind to the monuments of Farnborough Park. Whilst those buildings with architectural pretensions have been well maintained, lesser buildings, including a small apple store and a bier shed and several agricultural buildings, have fallen into disrepair and in some cases, total collapse. Those structures which helped the water to do interesting things are in a particularly parlous state and again have either partially collapsed or are about to…

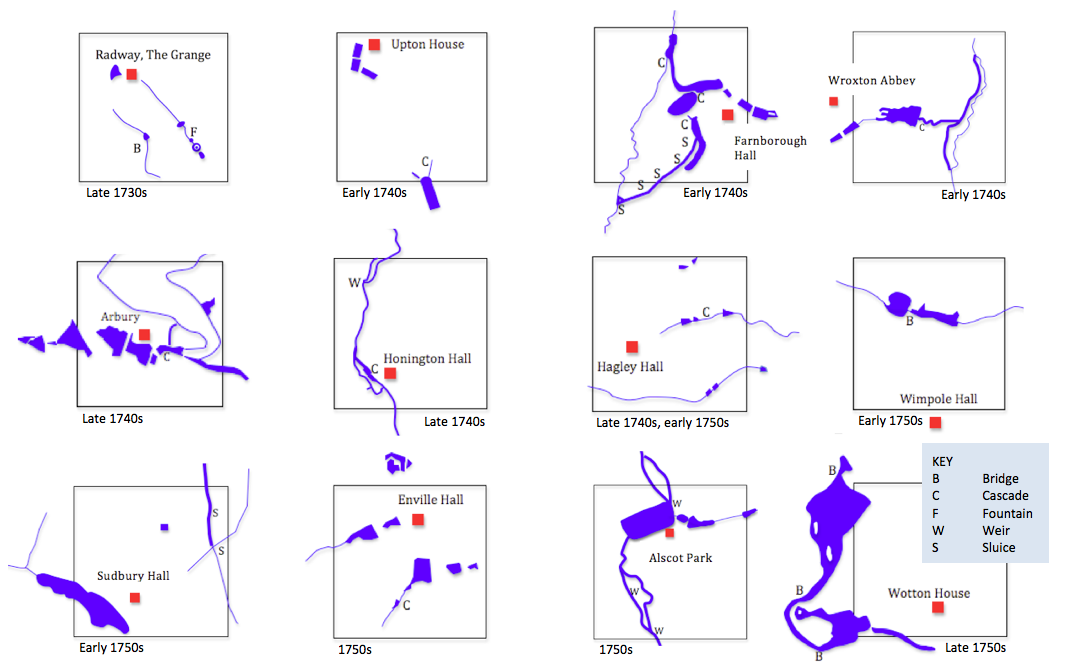

Following our chronological survey we will return to our central concern, the understanding of those elements within the eighteenth-century park linked to water and how they reflect ‘patterns of power and dominance’. We have touched on the answers to most of the questions posed in chapter 5 but two remain outstanding. The first of these is the question as to how it was all planned. The problems of assessing the contributions of a ‘gentleman architect’ have already been examined. Faced with these difficulties researchers Meir and Hawkes adopted the procedure whereby evidence of a visit to a site was fused with perceived stylistic traits to establish a corpus of work. It is no great criticism to point out the extremely speculative nature of this approach. Meir (2006: 217) especially, argues for the recognition of Miller’s fingerprints on a range of projects and suggests that, ‘The inventive use of water, and an ability to find successful technical solution to intractable drainage problems together form a major component of Miller’s “stylistic signature”’. She further cites an informal layout for lakes and a fondness for long thin waterways punctuated with sluices or cascades which occasionally are doubled up to run along side other existing water courses. The phrase used by Miller’s great-grandson to describe his involvement was ‘assisted by the advice of’ (Miller 1900: 61).

It is easy to see from Miller’s diaries how this assistance was rendered. Occasionally he would sit down and draw detailed plans (Hawkes 2005:161), but more often it was a walk in the park with Miller pointing out solutions to problems or opportunities for development, followed up perhaps with a letter ( Hawkes 2005: 164). This process of design through conversation throws open the possibility of dialogue between architect and patron and given the preponderance of classical detailing at Farnborough there is a strong case for William Holbech’s being the dominant partner. Miller did not have a good track record for classical buildings, indeed John Cornforth writing in Country Life dismissed Miller as someone who, ‘demonstrated no significant ability in working in the classical style at this date’ (Cornforth 1996 cited by Hawkes 2005). Apart from the five possible structures at Farnborough ( Figs. 34, 38, 39 and 92) Miller built only a handful of classical garden buildings during a thirty year career (Hawkes 2005: 391 to 408). Virtually all his other work was in the gothic style. The absence of gothic buildings at Farnborough indicates this strong lead from Holbech. If Holbech was giving instructions regarding the provision of classical buildings it is fair to assume that he may have made similar requests concerning unusual features like the amphitheatre and the Oval Pond. If we examine other water features attributed to Miller, the only thing at Farnborough typical of his work is the Serpentine River. In other respects both the scale and configuration of the works at Farnborough bear little resemblance to other projects (Fig. 93). The likelihood is that Miller was responding with advice and perhaps some technical expertise under the direction of a landowner who was trying to create a peculiarly classical landscape, which was not only reflected in the buildings, but also in the way in which earth and water were engineered. The source of inspiration was the vision, passion, perhaps even obsession, of the landowner.

The final question and perhaps the most challenging is what was the purpose of this large-scale landscape transformation? Individual landowners did not have to express or explain their reasons, even to themselves, so explanations can only ever be provisional, however, by looking at the wider context, we can venture some suggestions. There are four key concepts: the social politics of separation and unification, the demands of good taste, the power of imagination and the economics of the country estate.

Social Politics of Separation and Unification

Many commentators have stressed the ways in which eighteenth-century garden design was used in terms of legitimation, ‘a tool with which elites attempted to maintain power and authority over marginalized groups’ (Williamson 1999: 37). The estate is a means of control and domination by imposing a particular world view on a locality through landscaping whilst simultaneously restricting options for the rest of the community in terms of movement, access and labour. This is a powerful theme within Farnborough’s story. From the closure of the route to the holy well to the dominating effect on the landscape of the Oval Pond this seems to be about under-scoring inequalities of power. Williamson (1999: 37) did move away from this position taking the view that, ‘most acts of aesthetic landscaping…were primarily directed not towards "the poor" but to rival groups within the propertied’. In making this point he emphasized the closed nature of many parks of the period, however, Farnborough is a very open landscape, much of what is on offer is widely visible so perhaps Johnson’s (1996:145) more nuanced view that, ‘around the great house the gardens were planned as a mediation between the elite and the ordinary as well between Nature and Culture’ is more productive, reflecting interactions, both positive and negative, within the full spectrum of society. This is emphasized in Miller’s diaries (Hawkes 2005) where it is clear that he enters into relationships, within the context of the park, with all manner of men and women from lady to labourer. We can therefore take a more positive view of the park as a meeting place where certain boundaries can be crossed. It is equally obvious that within Miller’s social group, of which we must count William Holbech a member, as well as companionship there was also competition based on the notion of good taste.

The Demands of Good Taste

Opportunities for self expression were characterised by the fact that,

‘by the eighteenth century a patron could choose between one of a number of different architectural and landscape styles’ (Johnson 1996:152). If this was coupled with, ‘untrammeled or only very partially limited power over the exploitation and physical appearance of an extensive tract of countryside’ (Williamson 2007: 4) then the potential for making statements about one’s own aesthetic judgment was enormous. Holbech’s ten years in Italy, at a time when the Grand Tour was de rigueur, must have given him authority as an arbiter of classical taste amongst his social circle (Fig. 94). One can see his work at Farnborough as an exemplar as to what could be done but also perhaps an object lesson in the way in which tasteful could spill over into mannered if enthusiasm is given too free a rein. It was possible to be too imaginative and end up with that most despised quality, ‘the merely whimsical’ (Thoreau 1854: 19).

The Power of Imagination

In describing the park I have often found myself using the analogy, ‘it’s like an eighteenth-century theme park’. In developing a similar point about the gardens at Stourhead Harwood (2002: 50) writes of, ‘the recognition that what they were seeing were theatrically contrived settings, the juxtaposition of which suggested an organized collection of opportunities for imaginative play’. At the risk of falling into the trap of developing the ‘existential and isolated presentism of phenomenological perspectives’ (Hicks 2003: 321) one has to say that in experiencing the park today one senses a history of enjoyment. There has been a description, with some license, of the goings-on around the Cascade (Fig. 84) and there is a feeling that the disposition of the terrace buildings was to tantalize in the sense of, ‘I wonder what’s around the next corner’. From the erection of ‘toy’ forts (Felus 2006: 30) to the placement of hermit’s caves one was expected to use one’s imagination as a playful participant in the landscape (Symes and Haynes 2010: 33). Holbech’s scrapbook of newspaper cuttings (WCRO CR656/36) reveal him to be something of a sportsman, was he a joker too?

Economics of the country estate.

The concept of improvement is often linked to ideas of economic advancement, but Tarlow sees it as also demonstrating,’ the ownership of rational knowledge and taste, a general orientation towards the future and a selective rewriting of the historical and classical past’ (Tarlow 2007: 67). This combination of the productive with the decorative was praised by Switzer, ‘a whole estate will appear as one great garden, and the utile woven harmoniously with the dulci… I affirm that an even walk carried through a cornfield or pasture… is as pleasing as the most finished parterre’ (Switzer 1742: 8). Farnborough represents an ideal example of such a ferme ornée: the ponds are a source of fish as well as a venue for boating and the view towards the River takes in the pasture known as the Dairy Ground. A striking feature of the park is the way in which unproductive land is turned to recreational ends. Sourland Pond speaks for itself and it is noticeable how the Terrace occupies the steep, wind-swept brow of the hill leaving the summit and slopes for grazing. Ponds and pounds march along together.

The End.

The park’s purpose was intimately linked to the social fabric of the time and served many of same purposes as today’s gardens: supplementing the family diet, relaxation, exercise, entertaining and of course one-upmanship but, as with any archaeological site that exhibits a number of unique features, Farnborough Park remains both baffling and revealing. There are many unresolved questions about how the landscape was manipulated by Holbech and Miller but what is clear is that we have a classic case of the exploitation of a particular resource, water, in a way which demonstrates the acquisitive drive of the land-owning elite over several centuries. There is no access to St. Botolph’s Well or the adjacent pools. The River and Canal may be viewed from the terrace after paying an entry fee but the Serpentine River is becoming quietly lost amongst commercially farmed land to the south. Only Sourland Pond exists as a community resource with fishermen lining its banks and families from Banbury coming out to feed the ducks. (Fig. 1).

Aberg, F.A. (ed.) 1978. Medieval Moated Sites, York: Council for British Archaeology

Astill, G. G. 1993. A Medieval Industrial Complex and its Landscape: the metal working watermills and Workshops of Bordesley Abbey, York: Council for British Archaeology

Aston, M. 1985. Interpreting the Landscape, Landscape Archaeology in Local Studies, London: Batsford

Aston, M. (ed.) 1988. Mediaeval Fish, Fisheries and Fish-ponds in England, Oxford: British Archaeological Reports

Bailiff, I. K. 2007. Methodological Developments in the Luminescence Dating of Brick from English Late-Medieval and Post-Medieval Buildings, Archaeometry Volume 49, Issue 4, pages 827 to 851

Blair, J. 1994. Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire, Stroud: Alan Sutton Publishing

Buxbaum, T. 2008. Icehouses, Oxford: Shire Publications

Cannon, J. 1987. Aristocratic Century, The peerage of eighteenth-century England, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Chanson, M. 2001. Historical Development of Stepped Cascades for the Dissipation of Hydraulic Energy, Transactions of the Newcomen Society, Volume 72, pages 295 to 318

Cherry. R. 2011. Notes of conversation with local retired builder, 15.3.11

Chisholm, M. 1979, Rural Settlement and Land Use, London: Hutchinson

Corfield, P. J. 1996. The Rivals: Landed and Other Gentlemen in Harte, N. B. and Quinault. R. (eds.), Land and Society in Britain, 1700-1914, Manchester: Manchester University Press

Currie, C. 1990. Fishponds as Garden Features, c. 1550-1750, Garden History, Volume 18, number 1, pages 22 to 46

Currie, C. 2003. Archaeological excavations at Upper Lodge, Bushy Park, London Borough of Richmond, 1997-99, Post-medieval Archaeology, Volume 37, Number 1, pages 3 to 45

Currie, C. 2005. Handbook of Garden Archaeology, York: Council for British Archaeology

Currie, C. and Rushton, N. 2001. The Historical Development of the Court of Noke Estate, Pembridge, with an Archaeological Assessment of Canal-like Water Features, Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists Field Club, Volume 50, Number 2, pages 224 to 250

Duignan, W. H. 1912. Warwickshire Place Names, Oxford: Oxford University Press

English Heritage 2011. Farnborough Hall, Banbury, England, Record Id: 1304 Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest, http://www.parksandgardens.ac.uk/component/option,com_parksandgardens/task,site/id,1304/tab,history/Itemid,305/

accessed 12.9.2011

Felus, K. 2006. Boats and Boating in the Designed Landscape, 1720-1820, Garden History, Volume 34, number 1, pages 22 to 46

Gearey, B. R., Hall, A. R., Bunting, M. J., Lillie, M. C., Kenward, H. and Carrott, J. 2005. Recent palaeoenvironmental evidence for the processing of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) in eastern England during the medieval period, Medieval Archaeology, Volume 49, pages 317 to 322

Gosden, C. and Marshall, Y. 1999. The Cultural Biography of Objects, World Archaeology, Volume 31, Number 2, Pages 169 to 178

Harrower, M. J. 2009. Is the hydraulic hypothesis dead yet? Irrigation and social change in ancient Yemen, World Archaeology, Volume 41, Issue 1 , pages 58 to 72

Harwood, E. 2002. Rhetoric, Authenticity, and Reception: The Eighteenth-Century Landscape Garden, the Modern Theme Park, and Their Audiences, in Young, T. and Riley, R. (eds.) Theme Park Landscapes: Antecedents and Variations, Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Colloquium on the History of Landscape Architecture, volume 20

Hawkes, W. (ed.) 2005 . The Diaries of Sanderson Miller of Radway, Stratford-upon-Avon: The Dugdale Society

Haworth, J. 1999. Farnborough Hall, London: National Trust

Heaton, A. 2001. Duck Decoys, Oxford: Shire Publications

Hicks, D. 2003. Archaeology Unfolding: Diversity and the Loss of Isolation, Oxford Journal of Archaeology, Volume 22, Issue 3, pages 315 to 329,

Hindle, S. 2003. Crime and Popular Protest, in Coward, B. (ed.) A Companion to Stuart Britain, Oxford: Blackwell

Ince, L. 2011. A History of the Holbeche Family of Warwickshire and the Holbech family of Farnborough, Studley: Brewin Books

Jago, R. 1767. Edge-Hill, or the Rural Prospect Delineated and Moralised, London

Jewell, P. A. (ed.) 1963. The experimental earthwork on Overton Down Wiltshire, London: British Association for the Advancement of Science

Joy, J. 2009. Reinvigorating object biography: reproducing the drama of object lives, World Archaeology, Volume 41, Issue 4, pages 540 to 546

Karr, A. J. 1849. Les Guêpes, Paris: January Edition

Lawton, B. 2006. Building the Wilts and Berks Canal, 1793–1810, Transactions of the Newcomen Society, Volume 76, Pages 291 to 313

Liddiard, R. 2005. Castles in Context, Macclesfield: Windgather Press

Linnell, E. 1772. Farnborough Estate Survey, Warwickshire County Records Office Ref. z 403 (u)

Meir, J. 1997. Sanderson Miller and the landscaping of Wroxton Abbey, Farnborough Hall and Honnington Hall, Garden History, Volume 25, number 1, pages 81 to 106

Meir, J. 2002. Development of a Natural Style in Designed Landscapes between 1730 and 1750: the English Midlands and the Work of Sanderson Miller and Lancelot Brown, Garden History, Volume 30 number 1, pages 24 to 48

Meir, J. 2006. Sanderson Miller and his Landscapes, Chichester: Phillimore

Miller, G. 1900. Rambles Around Edge Hill, London: Elliot Stock

Mowl, T. 2006. Preface to Meir, J. 2006. Sanderson Miller and his Landscapes, Chichester: Phillimore

Mowl, T. 2010. Gentleman Gardeners: the Men Who Created the English Landscape Garden, Stroud: The History Press

Mowl, T. and James, D. 2011. Historic Gardens of Warwickshire, Bristol: Redcliffe

Muir-Beddall, A, 2012. Current occupant of Farnborough Hall, notes of conversation 30.8.12

Nares, G. 1954. Farnborough Hall, Warwickshire, The Home of Mr. R.H.A. Holbech, Parts I and II, Country Life, 115 (11 February 1954), pages 354 to7; (18 February 1954), pages 430 to 433

North, R. 1714. Discourse of Fish and Fishponds, London: E. Curll

O’Keeffe, T. 2010. Review, Cambridge Archaeological Journal, Volume 20, number 1, pages 148 – 154

Pauls, E. P. 2006. The Place of Space: Architecture, landscape and Social Life, in Hall, M. and Simpson, S.W. (eds) Historical Archaeology, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

Payne-Gallwey, Sir R. 1886. The Book of Duck Decoys, their Construction, management and History, London: John van Voorst

Pevsner, N. and Wedgwood, A. 1986. The Buildings of England Warwickshire, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books

Porter, R. 1991. English Society in the Eighteenth Century, London: Penguin Books

Radley, J. D. 2003. Warwickshire’s Jurassic geology: past, present and future, Mercian Geologist, Volume 15, number 4, pages 209 to 218

Roberts, B. K. 1987. The Making of the English Village, A Study in Historical Geography, Harlow: Longman Scientific and Technical

Roberts, J. 2001. 'Well Temper'd Clay': Constructing Water Features in the Landscape Park, Garden History, Volume 29, Number 1, pages 12 to 28

Salzman, L.F. (ed.) 1949. A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 5 Kington Hundred, London: University of London, Victoria County History, pages 84 to 88

Rodd, T. 1846. Catalogue of Books, Part II Jurisprudence and Political Economy. London: Compton and Ritchie

Sayer, D. 2009. Medieval waterways and hydraulic

economics: monasteries, towns and the East Anglian fen, World Archaeology Volume 41, Issue 1, pages 134 to 150

Schmidt, A. J. 2009. Review Journal of Social History, Volume 43, number 1, pages 242 to 243

Steane, J. M. 1984. The Archaeology of Medieval England and Wales, London: Croom Helm

Strong, R. 1998. The Renaissance Garden in England, London: Thames and Hudson