Farnborough 2012

Interim Report, Investigations at Site 3: The ‘Amphitheatre’

By Stephen Wass

Fig. 1 Volunteers clearing undergrowth from the site of the amphitheatre, October 2011

Centre 52˚08‘ 35.56“N 1˚22‘ 34.56“W OS Grid Reference SP42804961

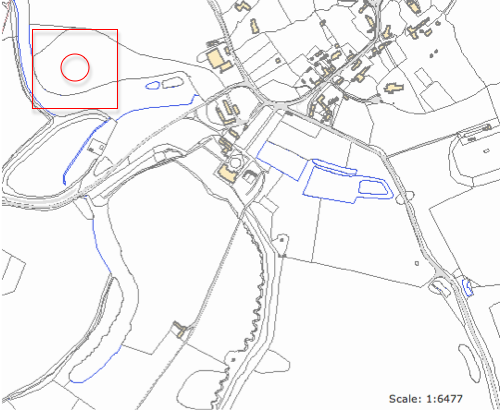

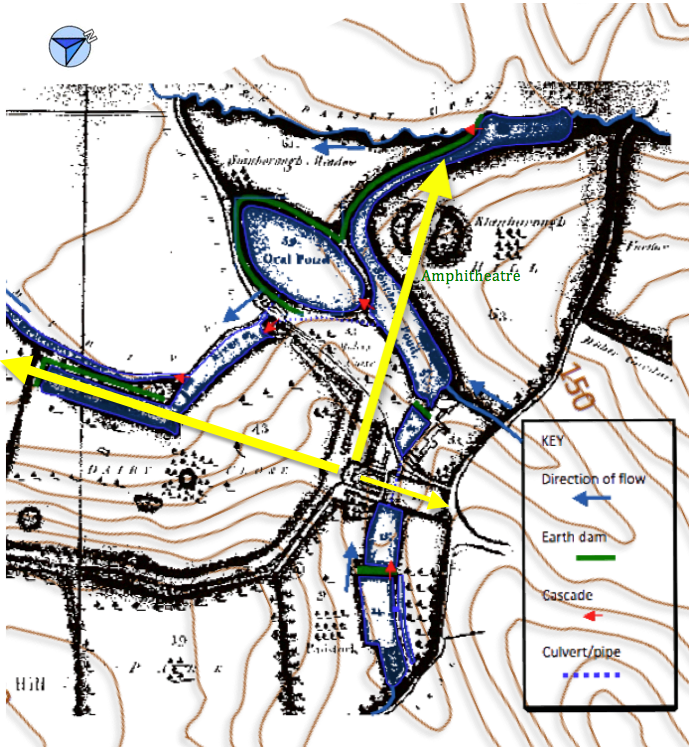

Fig. 2 Location map

Introduction.

Between Monday June 18th. and Thursday June 20th. 2012 investigations were undertaken on the site of the earthwork feature in Stambra Wood, sometimes known as Stanborough (Fig. 2). We have identified this as a type of garden feature known as an amphitheatre (see Discussion below). Although the park is on the English Heritage Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England Grade I Reference GD1003 (English Heritage 2011) no specific mention is made of the existence of the amphitheatre nor does it appear on the Warwickshire HER. Work this season was undertaken by a team of three local volunteers under the direction of Stephen Wass.

Initial analysis of the results strongly suggest that the monument originally consisted of grassy banks, ditches and terraces which were subject to some planting and formed not only a significant element in the landscape as viewed from Farnborough Hall but were also available for walking around on and possibly the staging of outdoor events. We do not at present have any evidence for putting a date on the construction of the Farnborough amphitheatre, however, evidence did emerge for use and management in the twentieth century.

Methodology

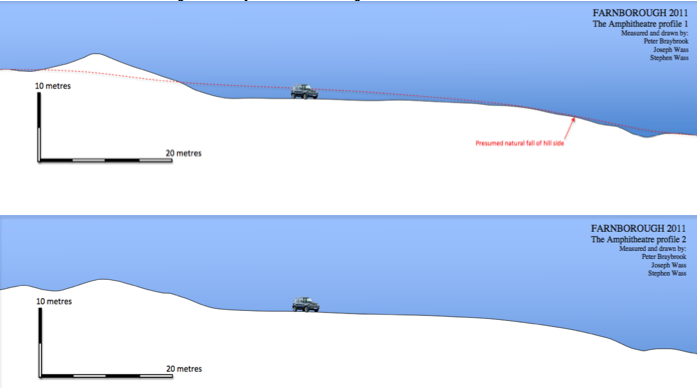

An initial sketch survey was undertaken amongst choked undergrowth in June 2011 but this was superseded by a measured survey (Fig. 3) following on from considerable clearance of brushwood by staff and volunteers from the National Trust later in the year (Fig. 1). As part of this survey the site was gridded up using wooden survey pegs at 20 metres intervals. Profiles of the earthworks were also drawn using an optical level and staff (Fig. 4).

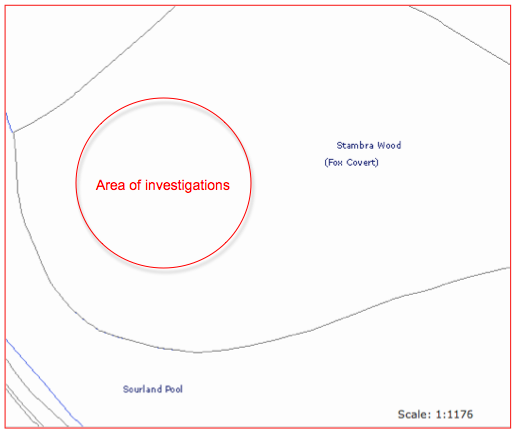

Fig. 3 the Amphitheatre showing location of interventions.

Fig. 4 The amphitheatre - profiles

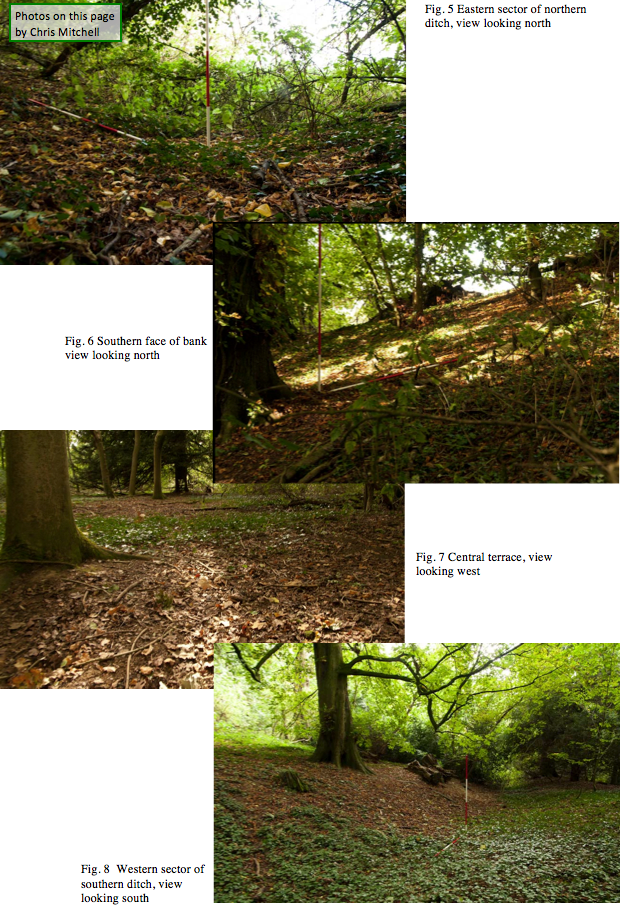

The earthwork consists of a massive crescentic bank (Fig.5) up to 8 metres high backed by a curving ditch (fig. 6) and fronting onto a large level terrace (fig.7). Beyond this to the south west the natural fall of the land reasserts itself and the ‘enclosure’ is completed by a further curving ditch towards the foot of the slope (Fig. 8).

Investigations in 2012 were based on three main strategies. The first of these, following some further clearance of the summer’s growth of nettles, was a detailed visual examination of the ground surface within the monument looking for traces of features such as partially buried walls or pathways or steps. The second strategy based on the observation of gravel paths in other parts of the park was to systematically probe the ground using a 45 cm surveyors arrow to try and determine the course of any lost pathways. This was done along the line of four transects at half metre intervals. At four locations (Fig. 3), where there appeared to be some buried features, test pits were excavated. Finally an intensive survey was carried out using a metal detector. One whole 20 metre square was completely covered whilst the rest of the site was surveyed by walking strips 2metres apart. The rationale for this was that we could pick up traces of features such as wooden tubs or planters or benches which had decayed in situ from the metalwork that such a process could be expected to deposit.

Results

The visual inspection revealed no surface indications of any additional structural elements present on the amphitheatre. Work on the profiles had suggested the possibility that the large bank had been terraced but where this was examined in detail any apparent terracing could be explained as the cumulative upcast from a series of badger setts.

The probing did not reveal the presence of any pathways. However, the presence of path like anomalies in three locations lead to the excavation of four test pits.

Test Pit 1

During probing a hard surface was detected at a depth of between 20 and 25 centimetres. A thin surface level of leaf mould and nettle (Urtica dioica) roots (001) was brushed away to reveal a dark reddish brown sticky clayey loam (002). At a depth of around 10 centimetres this merged with a sub-soil of dull yellowish brown compact clayey loam (003) which lay 15 centimetres above a compact substrate of ironstone. This was formed from irregular polygonal blocks between 10 and 30 centimetres across with an uneven but rounded upper surface (004). This was clearly the hard surface which had been detected by probing and represented a domed area where the bedrock approached a little closer to the surface than was usual. The soils were extremely homogenous with no inclusions and very little visible humic material apart from roots(fig. 9). The pit was back filled and the surface reinstated on the same day.

Fig. 9 test pit 1/ 004, view looking north.

Test Pit 2

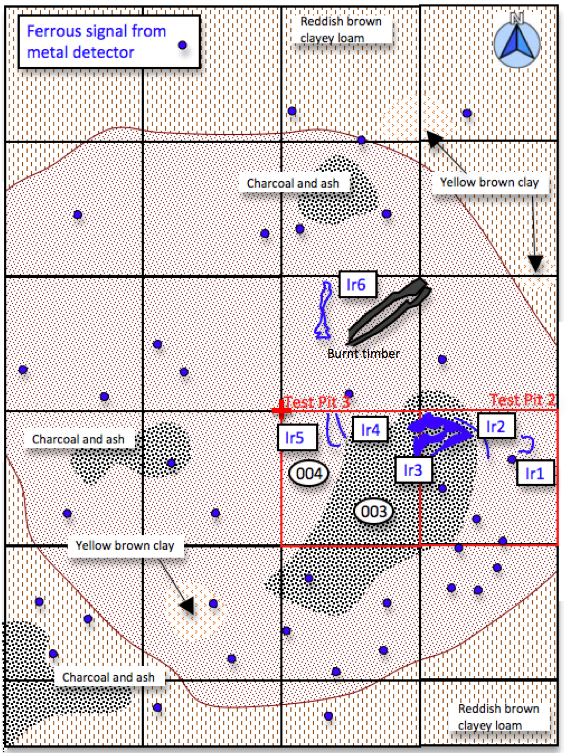

Test pit 2 was started on the basis of detecting a reddish gravel like deposit quite close to the surface. It was also in the vicinity of a good deal of scrap iron which had been seen lying on the surface during the clearing of undergrowth last year. Once the surface vegetation consisting mainly of Common Ivy (Hedera helix)and Solomon’s Seal (Polygonatum multiflorum) had been removed it became clear that the greater concentration of this material lay to the west and so in test pit 2 the exposed surface was towelled clean. A further selection of iron pieces was identified and the dark reddish brown clay found to be packed full of charcoal and larger fragments of burnt wood but no further investigations were carried out (Fig.10).

Test Pit 3

As test pit 3 was dug it became obvious that the red gravel like material (004) extended across much of the surface of the area and was initially interpreted as decayed brick. However, the adjacent deposits of charcoal and ash (003) made it seem more likely that the brick like appearance of the material was caused by the natural clay being partially fired by the extensive burning that had clearly gone on. The laminated appearance of this layer of charcoal and ash indicated the possibility of more than one fire on the same spot. These deposits bottomed out at a depth of around 15 centimetres onto a layer of tenacious brown clay (005).

Fig 10. Test Pits 2 and 3 and surrounding area

In order to determine the spread of burnt material surface vegetation was removed from 20 square metres of the surrounding area and the spread of 004 determined together with other concentrated patches of charcoal. A detailed survey using a metal detector was carried out and the position of ferrous signals plotted (Fig. 10) although none were investigated by excavation. The individual pieces of iron which had been seen on the surface were also drawn onto the plan, removed for photography and measurement and then replaced. Finally the Test Pit 3 was backfilled and the whole area recovered with swept back leaves.

Fig 11. Test Pits 2 and 3 and surrounding area, view looking north

Test Pit 4

Probing across the eastern terminal of the bank revealed so possible solid surfaces at a depth of around 15 centimetres. There was little surface vegetation to clear and erosion had made it difficult for significant amounts of leaf mould to accumulate so the ground surface was scraped clean to reveal a clean compact dull yellowish brown silty loam. There were a small number of ironstone fragments amongst what was otherwise an homogenous layer. The south east quadrant of the metre square was dug down to a depth of 25 centimetres and again proved to be free of inclusions and remarkably consistent in terms of texture and colour. The pit was back filled and the surface reinstated on the same day.

Fig 12. Test Pit 4 , view looking north

Metal Detecting

In order to establish general levels of signals from metal work an area of 400 square metres (Fig. 3) was subject to careful examination so that the entire area was covered by sweeping the detector head from side to side. The area was largely free from metalwork except for the concentration around the north west corner where further detailed sweeping and recording were carried out (fig. 10). Otherwise the remainder of the site was sampled by walking transects at 2 metre intervals from east to west aligned with the site grid. Remarkably no metal work was detected elsewhere on the site. The sensitivity of the detector used was checked on several occasions by burying and recovering modern iron nails so we can be reasonably confident that levels of residual metalwork on the amphitheatre are very low.

Discussion

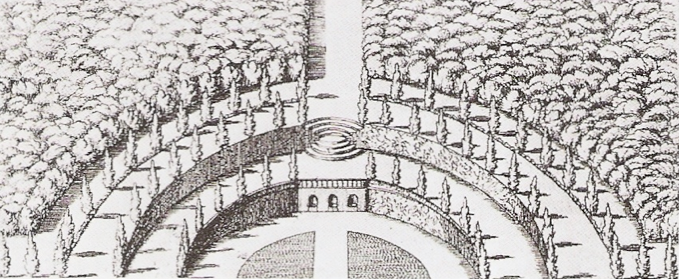

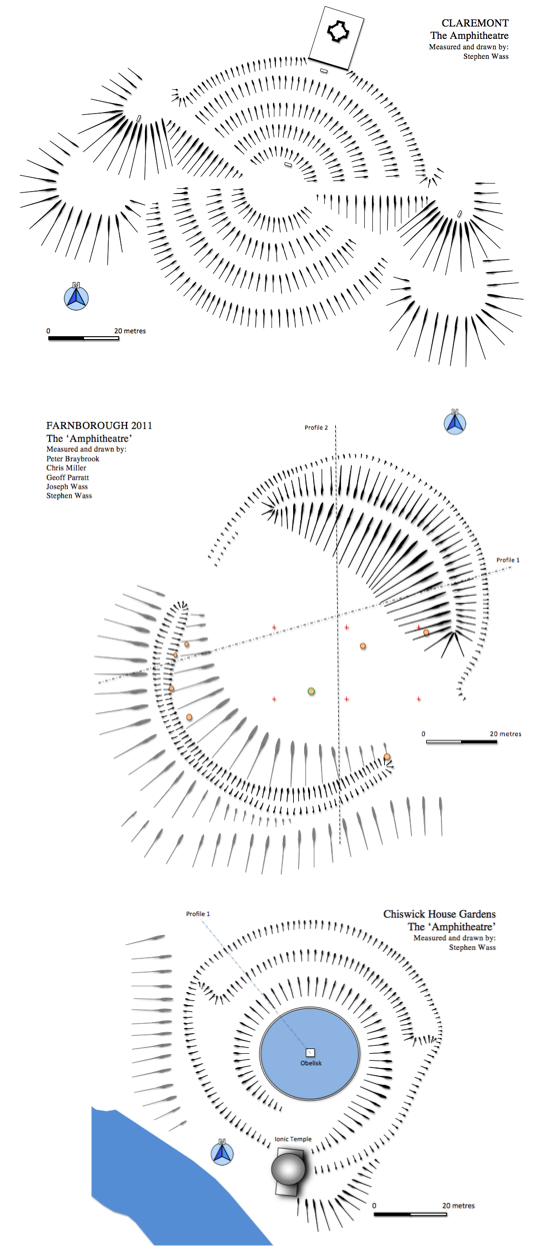

In the context of English landscaped garden design in the seventeenth and eighteenth century an amphitheatre is a circular or semicircular feature defined by terraces and occasionally banks and ditches which were both the focus for special planting and a venue to which or about which one walked. They clearly derived from a number of well known Italian renaissance examples. There are some indications that the earliest ones, at Wilton House, Wiltshire for example (Fig. 13), may also have seen performances of the kinds of outdoor masques and pageants which were popular in the seventeenth century. The amphitheatre at Wilton, now destroyed, was designed by Salomon de Caus for Philip Herbert, Fourth earl of Pembroke in the 1630s (Strong 1998: 147) This paved the way for Charles Bridgeman’s work at Claremont, Surrey (Fig. 14) around 1715 ( Mowl 2010:69) and Lord Burlington’s orange garden at Chiswick (Fig. 15) in the late 1720s (White 2010:28).

Fig. 13 The amphitheatre at Wilton House

Fig. 14 The amphitheatre at Claremont, anonymous painting of 1749

Fig. 15 Chiswick, the amphitheatre with orange garden and Ionic Temple, painting by Rysbrack c. 1728

Work is currently underway to draw up a gazetteer of all examples to be found in the United Kingdom but it seems likely that they were never a particularly common feature so the discovery of an example at Farnborough is an important addition to the corpus. The key question is in what way does the amphitheatre at Farnborough relate to the wider pattern of English garden design but we are hard pressed to make even a start on this in the absence of any dating evidence. We know that the feature was present in 1772 because the outlines are drawn as the boundaries of two shrubberies (Fig. 16) in an estate map of the time (Linnell 1772). One might assume that it was constructed as part of the major landscaping of the grounds in the 1740s under the direction of landscape architect, Sanderson Miller (Meir 2004:82 -93) and not be surprised that no contemporary record of it exists since this is a common feature of his work. Given William Holbech’s experiences on the grand tour and his evident enthusiasm for all things Roman (Haworth 1999) it could make sense for such a structure with its classical allusions to be incorporated into a landscape heavy with temples, urns and obelisks. On the other hand one gets the impression that by 1740, as an element in fashionable garden design, the amphitheatre was becoming distinctly passé. On stylistic grounds one might therefore be tempted to assign the monument to the seventeenth century. Could it have been a feature of the park created by the Raleighs? It’s existence as a pre-existing feature could explain the apparently low profile it seemed to occupy in the record of the Georgian landscape.

Whatever its limitations as a documented feature there can be no doubt of the amphitheatre’s dominance in the eighteenth century landscape. The south western aspect of the house is well known. From the lawn there is a clear view across parkland, a ha-ha sorts out the boundary, then we look along the line of the canal and down the avenue to the far distant College Farm. The view from the north western side of the house would have been more immediate and perhaps more striking. The level bowling green, again bounded by a ha-ha. opens onto a lawn which dips down to the waters of Sourland Pool and beyond that, above a grassy slope, the profile of the amphitheatre on the sky line with the broad central terrace being virtually at eye level (Fig. 16).

Fig. 16 Eighteenth Century estate map with contours overlaid showing main vista from principal house frontages

Comparisons with the well known examples of amphitheatres at Chiswick and Claremont prove instructive (fig. 17). Chiswick with its central pool with obelisk and the grand Ionic Temple is obviously a setting for a variety of architectural features (fig. 15). Careful examination of the ground at Farnborough reveals no such features, not even the barest trace of scatters of building material. The notion of moveable tubs for specimen plants is an intriguing one and concentrations of metalwork from decayed planters may have revealed a similar arrangement but no such deposits were found.

Fig. 17 Amphitheatres, comparative plans

There are some intriguing parallels with the Claremont amphitheatre. The size is broadly similar as is the orientation towards the south west. Of course Farnborough has none of the fine detailing of Claremont’s terracing and mounds but then it is important to remember that what we are seeing today is largely the result of Graham Stuart Thomas’s restoration of 1979 (Thomas 1979:117). As Elliot points out, ‘the restoration…was not properly archaeological at all ’(Elliot 2007: 12) so it is by no means clear what condition Claremont’s terraces were in prior to restoration and to what degree the work done was based on eighteenth century pictorial references. These do show, apart from grassy banks, white painted wooden benches placed at strategic locations (Fig. 13). Similar provision could well have been made at Farnborough but we were unable to find any evidence for what admittedly would have been very ephemeral features. What does stand out is that all three sites have a close relationship with water so that at Farnborough, obviously as a result of the local topography, the curving outline of Sourland pool mirrors the curve of the amphitheatre’s lower slope and seems almost to embrace it (fig. 15).

The existing planting on the amphitheatre is largely self sown however, there is one surviving yew (Taxus baccata) which could plausibly belong to the mid-eighteenth century and several yew stumps. The distribution of these suggests that there was an arc of yews lining the upper edge of the lower ditch. There are two on the central terrace and the site of one close to the eastern terminal of the large bank. Other planting in what is now Stambra Wood seems to date from the early years of the nineteenth century. This includes a number of beeches (Fagus sylvatica) which have been dated elsewhere on the estate by counting tree rings and a large Wellingtonia (Sequoiadendron giganteum). This indicates that during the remodeling of the park under the direction of Henry Hakewill around 1815 (Tyack 1994:91) a decision was made to convert the whole of Stanborough Hill to ornamental woodland (Fig. 17) thus obscuring the form, and indeed later, the very existence of the amphitheatre.

Fig. 18 View looking north west across Sourland Pool towards the site of the amphitheatre

There is an interesting dump of material that can be seen close to the eastern terminal of the lower ditch. Lying on the surface adjoining an existing path is a large collection of pottery and glass fragments (Fig. 19) which appear to date from the mid- to late-nineteenth century. We have no indication exactly when this material was dumped but again it suggests that by the late nineteenth century at least the amphitheatre site was sufficiently neglected so that it could be used to dump rubbish.

Fig.19 Some of the pottery on surface of dump, eastern terminal of the lower ditch, view looking south west (Photo by Chris Mitchell

During the clearance of undergrowth in the autumn of 2011 a number of iron fragments were noted lying beneath the ground cover. These were left in situ then rediscovered during this season’s work and shown to be in close association with burnt materials in and around test pits 2 and 3. Clearly a number of fires were lit here in comparatively recent times. Unfortunately no direct evidence for dating these fires was observed, however, the condition of the metalwork suggests that some period of time has passed to allow such serious corrosion to set in (Fig. 20). Indeed by drawing on parallels with iron objects noted on the ground surface in Sanctuary Wood near Ypres, Belgium these fragments could date as far back as the early years of the twentieth century. There is no direct evidence that the pieces were all part of a single artefact, indeed Ir7 is almost certainly not, however, the remainder could be convincingly put together to give the handles: Ir1 and Ir4/5 the body Ir3 and reinforcement Ir2 and Ir 6 of a large iron cooking pan roughly 45 centimetres in diameter. In the absence of these finds one could suggest that the fires were simply the result of burning fallen branches and the like as part of a programme of woodland management but ethnological parallels (Fig. 21) suggest the possibility of cooking being undertaken by a transient population either legitimately as could be the case of perhaps a scout troop or illegitimately by travellers of some description. The pieces of iron work were returned and repositioned on their original find spots .

Fig. 20 Iron work from around test pits 2 and 3

Fig 21. Cooking over an open fire with an iron pan, shepherds’ encampment mountains above Bazna, Transylvania, Romania May 2005

Conclusion

The earthworks in the woods above Sourland Pool represent a major piece of landscaping from an early stage in the park’s development. Further work needs to be done to explore parallels and investigate the amphitheatre’s place within the story of English landscape design overall. All those who have visited have commented on what a remarkable space it is and so it seems entirely appropriate to explore ways in which the site could be opened up and explained to the public whilst at the same time ensuring that the existing remains are conserved and appropriately presented.

Bibliography

Elliot,B. 2007. Bulletin du Centre de recherche du château de Versailles, Changing fashions in the conservation and restoration of gardens in Great-Britain.

English Heritage 2011. Farnborough Hall, Banbury, England, Record Id: 1304 Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest, http://www.parksandgardens.ac.uk/component/option,com_parksandgardens/task,site/id,1304/tab,history/Itemid,305/ accessed 12.9.2011

Haworth, J. 1999. Farnborough Hall, London: National Trust

Linnell, E. 1772. Farnborough Estate Survey, Warwickshire County Records Office Ref. z 403 (u)

Meir, J. 2006. Sanderson Miller and his Landscapes, Chichester: Phillimore

Mowl, T. 2010. Gentlemen Gardeners, Stroud: The History Press

Strong, R. 1998, The Renaissance Garden in England. London: Thames and Hudson

Thomas, G.S. 1979 Gardens of the National Trust. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson

Tyack, G. 1994. Warwickshire Country Houses, Chichester: Phillimore

White, R. 2010 Chiswick House and Gardens, London: English Heritage