HESDIN

The end of it all, engraving of the siege of Hesdin in 1553 after which the gardens were destroyed, view looking west

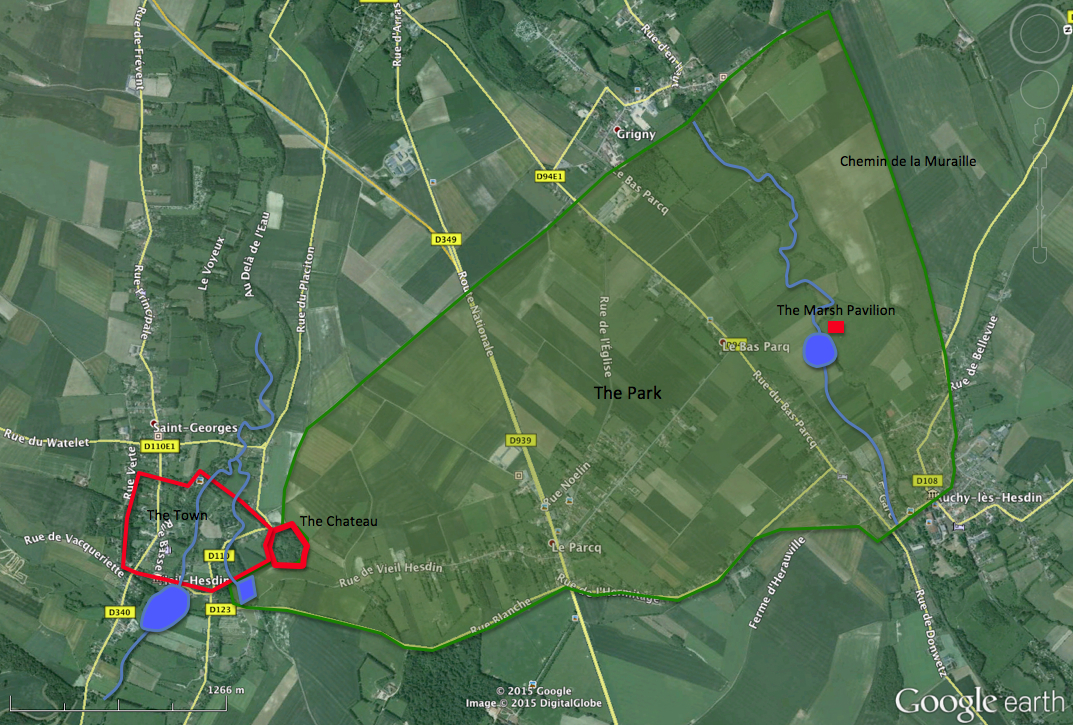

Our first excursion was to the site of the hugely famous and famously huge site of the park at Hesdin in northern France. This is not the place to tell the full story but suffice it to say that Robert II Count of Artois, on his return from foreign parts, most notably Sicily brought along with him cohorts of southern Europeans, including Italians and commenced work on extending and improving the park attached to his castle and town of Hesdin (Now Vieil Hesdin). The scale of this undertaking was enormous (see map below) as was the time and expenditure devoted to the construction of assorted fountains, pavilions and entertaining automata. Some of these were incorporated into the castle but others were scattered around the grounds, especially in a marshy valley to the north. You only really get to appreciate the scale of the place by getting lost – as we did – then driving round a lot.

We had an arrangement with Sebastian chairman of the Association des Amis de Vieil Hesdin (Visit their very comprehensive web-site.) to meet at the Espace Historique at 13, Rue de Hesdin. Unfortunately we fetched up at Rue de Hesdin in Auchy-Les-Hesdin, a small village set in the far north east corner of the former park. Having attempted to get directions by phone we made some progress in moving on to a second village called not surprisingly Le Parcq right in the heart of the complex. From there we followed our host by car down to where we should have been outside the small museum in Vieil Hesdin itself. We were met there by two further representatives of the association and shown their collection, some Romano-Gallic material, lots of small metallic medieval finds, presumably they have some active detectorists in their ranks, some nice late medieval pottery and a few, a very few, architectural fragments.

The town coat of arms with the museum just around the corner.

Back into cars to return to Le Parcq. This took us past the wooded knoll on which the chateau once stood. Unfortunately the site is in private hands and the current owner does not encourage visitors. We then drove up onto the plateau past the site of the former menagerie. The land up here is very open and windswept and obviously has been intensively cultivated for some time, a creamy brown chalky soil with flints. A fine misting drizzle didn’t help visibility much. Up at Le Parcq we parked outside the Mairie and were introduced to the mayor and the lady responsible for looking after Le Jardin D’Eden, a modern evocation of the park’s former glories including much interesting planting and a variety of pleached hedges and topiary representing the parks previous fauna.

View looking south towards the site of the chateau lurking in the woods. View looking east across the site of the park from the location of the menagerie.

The tribute garden at Le Parcq: Sebastian explains and the giant rabbits are on show.

The expedition, lead by the mayor, then returned to Auchy-Les-Hesdin. We left the cars and walked a short was along the footpath de Pays Tour du Ternois Sud to look out across the valley of the Ternoise towards the site of the Marsh Pavilion, again a heavily cultivated landscape but with some hints of earthworks in a small area of pasture to the south of the path. We retraced our steps and then took ourselves up along Le Chemin de la Muraille flanked to the south by a massive terraced bank with the tiniest traces of the 11 kilometre wall which once enclosed the park. Built of flint nodules with a soft chalky mortar it has largely been removed for much of its perimeter either for recycling or simply to clear the land.

Looking south across the valley of the Termoise the site of the Pavilion to the right. A sixteenth century painting of a fifteenth century tapestry of the Pavilion, probably also looking south.

Walking the Chemin de la Muraille, the park boundary to the left, view looking west. A tiny fragment of flint walling at the top of the bank

The power of the Ternoise, looking from the bridge in Auchy-Les-Hesdin to the north east.

After saying goodbye to our hosts we drove back through Auchy-Les-Hesdin pausing for a moment to photograph a remarkable 19th. Century complex of sluice gates, mill races and what have you associated with an early industrial complex south of the river. An admirable testimony to the energy to be had from the Ternoise. After lunch at the bar back in Vieil Hesdin we spent time exploring the site of the town. Exiting through the gap formerly the site of the Porte de Puterie we walked along the line of the southern defences of the town a massive ditch and rampart formerly lined with walls and towers. Then we walked down through the town towards the chateau then over to the east side of town where the maps showed a series of fish ponds and various areas of garden. There were virtually no surfaces trace of any of these features, curious really when you consider for example the landscape around Kenilworth Castle with a whole series of earthwork remains, even the average deserted or partially deserted English medieval village site has more to show. Where, for example has all the stone gone? Was it shipped a few kilometres down the river to build the new settlement of Hesdin after the disastrous siege in the mid-sixteenth century. Very puzzling and rather disappointing given the magnificence of its reputation.

The place to go for very good chicken and chips and canaries (not on the plate of course). View through the site of the Porte de Puterie looking west.

The centre of Vieil Hesdin looking east. The site of the pond next to Petit Paradis, looking north west. The site of the Grand Vivier looking south.

Annevoie in the summer with water and visitors. View looking south west towards le Grand Cracheur (Thanks to Denzil of Discovering Belgium for this image)

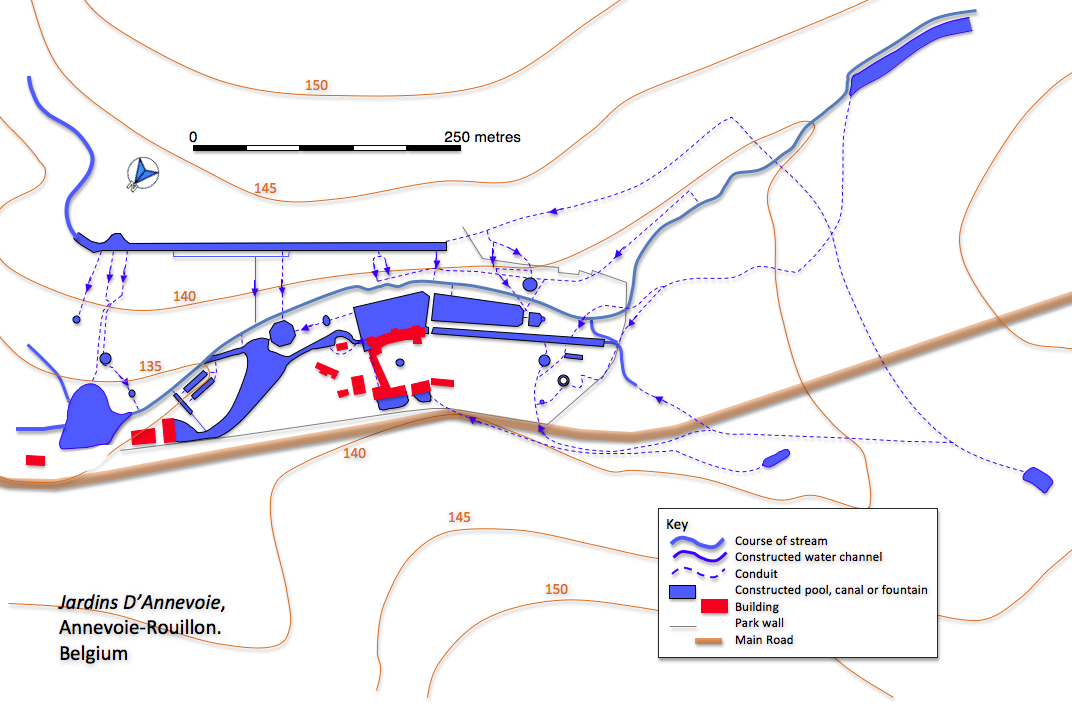

Our second visit was on the following day to the Jardin D’Annevoie in the Belgian region of Wallonia, about 15 km south of Namur. Designed and laid out under the direction of Charles Alexis de Montpellier in 1758 they have been maintained and added to over the past two and a half centuries and exhibit an extraordinary variety of water features. Although more of a period with Farnborough what is special about Annevoie is the fact that everything remains pretty well in working order.

On the day we were met by Olivier, one of the gardeners who took enormous pains to show us how everything worked and took the top off every manhole cover and pointed out every drain in his efforts to demonstrate the workings of the garden. In many ways it occupies a very similar situation to Hanwell, packed into a valley amply supplied with water from a variety of springs. Essentially one of these feeds into a high level canal which borders the south side of the valley whilst the others lie further up the valley to the west. The current throughput of water at Annevoie seems rather higher than we have currently at Hanwell but then we are comparing a well maintained system with something which was been out of order for nearly 350 years.

Dried up and rather battered fishy heads?

Our guided tour began at the downstream end of the garden which of course makes sense if you are here for the spectacle because that’s how you enjoy the best views of the cascades and waterfalls and ensure any water control systems do not become too obvious.. Heading south from the visitor centre, close to which are a pair of disconnected but formerly spouting decayed goggle eyed fishy heads, our first stop was at a pair of rectangular pools which had been drained for maintenance.. These supplied a pair of small basin fountains from an overflow pipe near the rim of the pools. Excess water was managed through a vertical pipe which stood a little higher and fed water directly into the channel below the basins. In order to empty the pools these pipes had been lifted out of position so the water accessed the lower exit point directly. The entry route for water into these pools was by another pair of fountains which produced fan shaped sprays of water.

The basin and outflow channel at the foot of the divided pool, with the water levels The down stream end of the eastern most section of the divided pool the pipe

low a lot of modern patching can be seen, view looking south east. that drains off the water when the pool is full lies on the grass, looking east.

Detail of the fan shaped nozzle at the top end of the divided pool.

Next up was Le Grand Eventail (or Le Gros Bouillon or Neptune’s Cuff ) which lay at the head of a small canal and was supplied by a channel which more or less bisected the garden and which we speculated may be the original stream that cut the valley, albeit in slightly canalized form. Olivier demonstrated the procedure for altering the fountain jet with a long L shaped tool as well as the mechanism for altering the rate of flow to the fountain. This was essentially a perforated iron sheet which allowed a modest flow and also of course trapped debris but which could be lifted or removed to create the grand effect. A little further up stream was Le Grand Cracheur which boasts a water jet over 7 metres high and was fed from the Grand Canal although on this occasion it was turned off.

View looking south west towards a much reduced Grand Evantail. To show what it can do Olivier removes the metal screen holding back the water

--- and adjusts the nozzle with the appropriate tool - no doubt it has a special name. White water displayed in the English Waterfall fed from the Grand Canal, view looking south east.

Lined up behind Le Grand Cracheur (the Big Spit, sorry) was the strictly symmetrical Cascade Franšais which was supplied via a culvert from the large pool in front of the Chateau. This is one of the earliest features on site. The picturesque English Waterfall fed into the stream from the south spreading out over a rocky talus to generate the maximum amount of ‘white water’. We also passed by the bottom of Le Buffet d’eau a feature added in 1760 of which more later.

The Buffet d'eau, also fed from the Grand Canal, but not today, view looking south east.

The Cascade Franšais looking down stream to the north east plus detail of the channel that feeds it from the castle moat.

Passing to the north of the Chateau and enjoying the view along the 168 metres of the Little Canal and the equally decorative Grand Drive with its engaging two dimensional cast iron trompe l’oeil statues of the four seasons we came round a corner to a stone-lined circular Bassin de l’Artichaut. Here a central pipe opened out to give six jets, two of which were temporarily blocked. Originally these terminated in bronze sculptured pipes designed to look like... yes, artichokes. Water for this was brought in from a piped source set in a walled terrace to the north where again there was a small silt trap and inspection chamber. Around another corner was a mossy boulder with a hollowed out basin and a central water jet operated from a channel that originates in an apparent spring to the west. Olivier demonstrated an effect on La Fontaine de l’Amour, as it is called whereby cupping his hand be could contain the water and then by lowering his hand force it down into the basin before suddenly releasing it with predictable consequences.

Spring, full frontal and sideways on.

The Bassin de l’Artichaut and its water supply, a pipe brings water into the silt trap on top of a stone terrace to the north.

Olivier has just played his party trick on La Fontaine de l’Amour, unfortunately I missed it.

Next up was the Salon du Sanglier where a rather fine if slightly eroded stone boar stood on a small hillock surround by a ring of water which flowed along a channel originating in a seemingly natural spring emerging from under a rock set in an arched opening in a wall… which is probably entirely artificial. This runs into the Little Canal over a feature called Les Nappes d’eau, a double cascade with a wavy edge defined by shaped iron plates. These have to be cleaned every day to prevent the build up of algae which takes the crispness of the profile of the falling water. The name refers to the way in which the smoothly flowing water resembles a well draped table cloth. A variety of other flows are cleverly managed in this part of the garden by bringing channels in at different levels and in some cases having one cross over another, in one instance in a cast iron aqueduct.

Olivier points out the water supply to the circular moat which confines the boar. A small decorative spring emerges from under a wall at the west end of the garden.

The Nappes d’eau view looking west.

Olivier demonstrates the cleaning technique to ensure a smooth flow... et voila!

The complex flow of water as it comes in to the garden at its western end: a sluice gate just south of the Nappes d’eau and a small aqueduct taking water to the pond known as the Mirror.

Following the line of the stream back now to the east we reached Le Rocher de Neptune a slightly cut down example of the kind of grotto we saw gracing so many Italian gardens. Small torrents of water flow in at two different levels, according to Olivier, from two different sources. The figure of Neptune is leaning on an open mouthed vase which presumably also issued water in the past. I wonder given the iconography if this were not initially designed to represent the titulatory deity of the local river the Meuse.

Neptune's Rock, in the English style... looks a touch Italian to me, view from north.

Finally we reached the west end of the Grand Canal, a construction over which considerable trouble was taken. According the guidebook water is drawn into the canal from springs around 1.6 km to the south, round in the next valley actually. The water was conducted via a pipe line which in places was carried on raised banks up to 10 metres high where the relief demanded. However, the number of effects actually powered from the canal are comparatively limited namely La Fontaine Triton, Le Buffet d’eau, Le Grand Cracheur and the water features in the flower garden created in 1952. The northern side of the canal, which is stone lined, is in good repair as would be expected on its downhill side, but slightly tumbled along the other side.

Verna and Olivier discuss the finer points of hydraulic engineering, looking north easy along the Grand Canal plus detail of the southern margin, water levels are kept quite low at present.

We spent some time examining the arrangements for supplying water to Le Buffet d’eau. This began with a stone lined conduit which emerged between the twin figures of Neptune and Amphitrite. The flow of water was controlled by a couple of large stones which simply sat in channel and as the angle they sat at was adjusted so the passage of water was altered. An extraordinarily simple yet effective mechanism yet one which if the stones were removed would leave little trace. The outer wall of the pool below the statues curved inwards to divide the flow of water with minimal turbulence into two exit pipes which then fed a series of fountains in individual circular basins, four pairs in all, before emerging in a series of mini-cascades emptying in to the stream.

The top of the Buffet d'eau, Neptune and Amphitrite from the back side with the water channel and regulating stones in place, view looking north west.

The onward channel, view looking west and the first basin with channel to feed the easternmost chain of fountains, looking north.

Water for the rocky cascade noted earlier was taken from two points along the length of the canal, conducted in channels which ran parallel to the canal then merged at a right angled confluence before plunging down the hillside. The final series of features fed from the canal were introduced to the gardens in the 1950s to enhance the opportunities for floral displays. Although comparatively recent in construction the methods for managing the water were essentially the same as those used in earlier parts of the garden. Here the flow of water was distributed between several fountains by taking multiple stoneware pipelines from square silt and leaf traps. The fountain heads themselves had been removed for maintenance but had been threaded onto the iron pipes which carried the water into a vertical position for delivery. Raised vertical pipes took the overflow from each basin down to the next series of fountains before emptying, as everything ultimately did into a large mill pond which powered a mill at the easternmost limit of the garden. Interestingly before ultimately flowing into the Meuse the water was employed in a series of forges and mills further down stream which were instrumental in generating the wealth which paid for the gardens upstream.

A sluice gate between the Grand Canal and the pipe to feed the 7 metre high Grand Cracheur. Overflow channels from the Grand Canal, view looking north east.

The east end of the Grand Canal, the feed channel comes in along the contour line from around the corner, view looking east.

Features from the 1950s Flower Garden, sluice gates, silt traps and outflow pipes.

View looking south up the quiescent Flower Garden plus a summer view looking north towards the mill pond and mill on the right (Thanks to Denzil of Discovering Belgium for this image)

This map is a compliled from a hand coloured map from in old handout from the gardens, the current guidebook and the Belgium Topographical Map Site

plus a few on-site observations, it is still rather speculative in places.... I need to go back.

HUY

Le Bassinia, a photograph of a photograph of an excavation.

Quite by accident we popped into Le Grand Curtius, the only museum in Liege open on a Monday should you be interested and there was a display on there relating to a late medieval fountain in the centre of the town of Huy, about 15 km west of the city. Structural problems had lead to a full scale dismantling, excavation and restoration of the monument. Friends of the Hanwell plastic child’s spade will be delighted to know that featured in the museum display cases were a couple of ‘matchbox’ cars which had been lost in the fountain as well as other knick-knacks and debris dating back to the fourteenth century. What was particularly interesting was the archaeological work that had been done on the water supply and the actual plumbing of the fountain itself, an interesting mix of lead pipes – largely on the way in - and terracotta - mainly on the way out. All of it quite complicated but carefully excavated and recorded. It will be a priority to make contact with the excavators and get hold of the final report. By the way, the illustration in the side bar is the crowning figure from the dismantled fountain, now preserved in the museum.

Some of the collection of small finds from Le Bassinia.

MODAVE

Our final port of call in Belgium was the Chateau of Modave, around 20 km south west of Liege. Its main claim to fame is that in the seventeenth century a carpenter from Liege called Rennequin Sualem designed and built a water wheel and pump to lift water from the river Hoyoux nearly 60 metres up to a water tower from which water was then drawn off to the chateau and garden although the audio commentary – what a source – did hint that the idea may have been copied from the gardens of the Coudenberg Palace at Brussels which had contained a similar engine designed by Solomon de Caus! Whatever the case the water tower survives and after an interesting tour of the chateau we were taken by a staff member, Benoit, to examine it.

The Chateau de Modave view looking north west.

Fountain and basin in the Little Hall, seventeenth century... getting water up to it was a problem, view looking south west from terrace the Hoyoux is 60 metres below.

More uses for water, an elegant water closet and zinc lined bath and the provider for both: a model in the basement of the famous wheel and pump.

Access is normally quite restricted as the water company Vivaqua own the park and maintain it as a nature reserve in order to preserve the integrity of the catchment area for the water supply for Brussels. So it was something of a privilege to explore this area. The tower with an internal diameter of 3.8 metres survived to a height of around 7 metres although much of its eastern side had collapsed. There were big questions as to how the whole thing had been organised. Subsequent landscaping had removed all traces of the site of the original wheel and pumps although there was something of a shallow ravine which seemed to climb up to the tower. Presumably the water was contained within lead piping, think of the pressure and emptied into a tank in the tower. There was no sign of any fittings, either internal or external which could have supported such a pipe, however, despite its ruinous state one had the impression that parts of the exterior had been at least re-pointed if not rebuilt. The tower itself was clearly never a water tight structure so I assume a metal tank was located in the upper portion, possibly where there is an internal ledge at about 6 metres. There is also a question as to how the water was conducted from the tower to the chateau and garden. Benoit told us that some work had been done with an infra-red scanner to try and locate the pipes but to no avail. There is a sunken track way which links the tower to the garden but no sign of any pipe work.

The water tower from the north west and the east.

View looking west down to the river and the view looking north east back towards the chateau, the line of the pipe must be somewhere along here

As an added bonus we were taken down to the river side at the foot of

the castle rock to see the nineteenth century replacement for the

original wheel and pump. A suitably industrial spectacle with a wide

iron wheel and associated pump in a rather elegant pavilion but driven

not by the river but from a leat running along the east side of the

valley.

The rather elegant nineteenth-century pump house, view from south plus mill leat.

The internal workings: the wheel and the pump.

HEIDELBERG

The rather elegant nineteenth-century pump house, view from south plus mill leat.

The internal workings: the wheel and the pump.

HEIDELBERG

I know it's a cliche but you just have to get these classic views in. The castle at night and by day, the gardens occupied the area to the left of the castle, views looking south west from across the Neckar.

The final site of this tour was a suitable climax to the whole enterprise, the Hortus Palatinus at the castle palace of Heidelberg. The importance of Heidelberg to our study lies in its royal connection to James I through his daughter Elizabeth who married the Elector Palatine Friedrich in 1614 and the fact that work on the gardens from 1614 to 1620 were undertaken under the direction of Solomon de Caus. Indeed many authorities describe the garden as his master piece although as we shall see there remains uncertainty as to what was actually built.

Our guide and host on this occasion was Professor Dr. Hartmut Troll, Stellv. Leiter Objektmanagement und Historische Gńrte who brought along a colleague with a remarkable key that seemed to open everything. After meeting up outside the new visitor centre we began our tour by examining two eighteenth century elements of the castle’s water supply. First the Lower Elector’s Well of 1767 which was actually down in the moat (formerly home to stags and bears ) on the south side of the castle then the slightly earlier Upper Elector’s Well of 1738 which stood on the same level as the main terrace of the gardens. Both structures shared the same general layout. Water, brought in via a conduit from the slope to the south was fed into a two part tank in the floor accessed by steps. The Lower well has a curious arrangement. The water seems to enter through an oval profiled conduit then drops via a vertical pipe into a small rectangular chamber both of which lay behind a barred and locked gate (of course we had the key ). Water then flowed through two copper pipes into a gravel filled rectangular basin before over flowing into a clean tile lined one which was approached by three steps. The well chamber is also notable for the remains of a decorative scheme which included two niches and a sculptural element, presumably of a river god with attendant urn. A rectangular cistern roughly 8 metres by 4 metres and around 3 metres deep, with steps down at the south west corner was fed from the lower well house.

Exterior of the lower well looking south. Decorative elements and entry to culvert. Settling tank and access steps.

Culvert: profile of upper channel. Descending pipe and lower channel.

Detail of pipework in outside access to supply, you can see from the holes the pipes have been repositioned. Open cistern to the west, view looking west

The upper well has a similar arrangement with a two part tank with steps but the water is brought in via a single pipe from a semi-circular gutter like feature leading out of a further tank. There is an additional square section conduit which brings water in from the west. The upper well is lined with carefully dressed red sandstone, like pretty well everything else round the castle.

The upper well house, view from north east.

The interior with access to culvert and access tank, looking south.

Details of access steps and feed pipe.

The conduits: inner chamber, overflow channel and additional side conduit.

Ascending two levels above the upper well we reached a lengthy terrace which culminated at its far eastern end in the Triumphal ‘Gate’ of Friedrich V but was lined on its southern side, just opposite the castle, with a series of stone built structures set against a tall terrace wall to the south. Plans of all these features were published by De Caus in his 1620 volume on the Hortus Palatinus. The first thing that is clear is that these buildings became very ruinous to the point where the front walls and columns survive to a height of around a metre. The debris was obviously cleared away at some time, possibly in the period 1923 – 25 when the guide book notes that ‘restoration of the terraces and ruins of the castle gardens by Ludwig Schmeider’ were carried out. This restoration meant at the very least that walls were repaired and repointed and capped. Examination of the surviving walls suggests that the scale of this work was very extensive which may explain the comparative lack of features that may be associated with the hydraulic mechanisms associated with the buildings.

The Gallery: niches in eastern side of gallery view looking south and holes cut in the walling of the niche at the east end of the gallery, view looking east.

The first of these we examined was known as the Gallery and consisted of a long rectangular hall fronted by a columned arcade. In the centre at the rear was an additional rectangular chamber with a grotto set into the terrace to the right. The walls were lined with semi-circular niches and closed off with stone slabs to create pools where fish were kept. There are a few significant differences between De Caus’s plan and what survives on the ground, there are no traces of the four rounded recesses set into the rear of the large rectangular area and in plan those niches which do survive have a much shallower curve than portrayed in the 1620 drawing. Without a much more detailed examination its hard to know if this is the result of changes to the original scheme for construction or the effect of later restoration. The grotto is currently in use for storing building material and equipment.

The Gallery: detail of construction of pool at base of niche, and the rectangular chamber without any niches to speak of, view looking south west.

The Gallery: the west end looking south west and the interior of the grotto looking south.

The Long Vault: views looking south west and south east.

Immediately adjacent to the west is a longer range of buildings similarly set against the terrace to the south which were collectively known as the Long Vault. The western most section was for storing tender plants over the winter, the middle section accommodated a water organ and apparatus for operating automata in the next chamber which contained two connected thin rectangular heated pools with apsidal ends to the east and west. There are three small but essentially identical rectangular chambers set into the terrace which we were told were the location of ovens for heating the complex. Each of these had a similar set of holes cut into the rear wall, presumably for associated pipe work.

Detail of the apsidal end of the western most pool at the eastern end of the Long Vault, the chamber for machinery is behind it to the right, view looking south west.

The Long Vault, the easternmost furnace room: rear wall looking south, exterior of chamber looking south, detail of downward slanting cut.

The long (nearly 300 metres ) thin (around 6 metres) Palmaille Court (think pall mall a kind of combination of golf and croquet) runs along to the east past another small grotto set in the terrace and an enclosed stair case that lead to the top of the terrace wall. This culminates in a grand ‘triumphal arch which was formerly crowned by a large statue of Frederick V. The top of this final terrace now carries the road Schloss-Wolfsbrunnenweg and this with associated landscaping has effectively removed any trace of water tanks and control mechanisms for delivering water to the features below, however, there is a late nineteenth-century conduit house which astonishingly our key also opened and we were able to take a look at what is evidently the current supply to the castle gardens. The area behind the site of Frederick’s statue has been built over but there is a lot of heavy duty buttressing of the terrace walls hereabouts and this angle of the garden lies above the main grotto and fountain area and below a well marked valley running down the mountainside from the south east, a possible location of some kind of large cistern to maintain the water supply to the wonders below?

View looking east6 along the Palmaille Court. Entry to the Small Grotto from Palmaille Court view looking south.

Small Grotto interior: large niche in south wall and decorated niche in east wall.

The Small Grotto: oculus and descending pipework. Culvert below the steps up from the Palmaille Court plus modern services.

Steps up to Schloss-Wolfsbrunnenweg view looking south.

Nineteenth-century conduit house south of Schloss-Wolfsbrunnenweg: view looking south west and interior view of pipework,

Triumphal Gate of Frederick V: Detail of walling and rather clumsy niche, general view from west and heavily buttressed walling to north - could this have supported a large cistern?

The Elliptical Staircase, view from south west and detail of water feature from south.

Again we were very fortunate in being allowed inside the normally locked large grotto and so were able to examine the remains of the cascade set in the east wall and other tanks and cisterns some of which may have been brought here from elsewhere for storage. Studying the printed image from the De Caus book Verna pointed out that the illustration as displayed is in fact a mirror image of what exists in the ground, a point she was able to deduce from the asymmetric poses of the stone boars. A small attached chamber at the south end of the complex feels like the kind of place where the various mechanisms (it would take an hour to see them all De Caus claimed ) could be controlled from.

The Water Parterre and Father Rhine with entry to the Great Grotto, view looking north east. Statue of Father Rhine view looking north east.

Inside the Great Grotto: general view looking north east and detail of stone basins at foot of cascade, looking south east.

General view of cascade looking east. Rectangular basin in niche on northern side of main chamber

The Great Grotto:a curious arrangement of basins in the side chamber, the pedestal basin may have stood in the main chamber originally

Water in the castle courtyard: the

seventeenth-century fountain looking north east, the medieval well house

looking south west and the latter pump and basin from the east.

More courtyard views: the Library

Building from the east, the Hall of Mirrors building looking north and

the Friedrich building looking north west.

This was the end of our time with professor Troll and his colleague and we expressed our thanks in fulsome terms. After saying our goodbyes we returned to the castle courtyard to take a look at the medieval well, the seventeenth century fountain and the nineteenth century pump as well as grabbing a beer and a bratwurst. We then took a final look round the gardens, taking in the famous Elizabeth gate allegedly built overnight on the instructions of the smitten Elector, before following a twisting path down towards the Karlstor and a stone lined channel which continued to function in draining at least some water from the gardens.

The Elizabeth gate of 1615 designed by Solomon de Caus, all views from south: statue niche converted to gun port, posing visitor and detail of sculpture.

The outflow of water to the north of the castle gardens: two channels merge, view looking north and detail of stone lining.

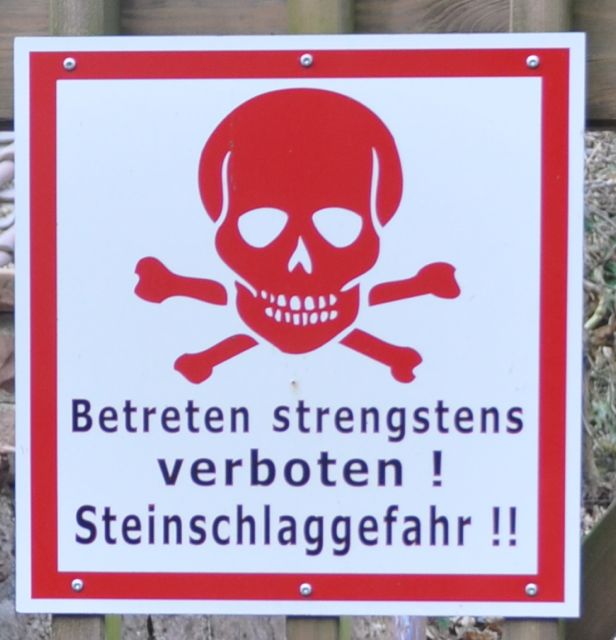

Sometimes not even a hard hat is enough.

It's irresistible, a final view of the castle plus the Hercules Fountain of 1701 in the Marktplatz, view from south and our accommodation, the late medieval hostelry and dueling hall, Hirschgasse, from north.

And so that was it. As always in these cases we only really were able to skim over the remains and as ever came away with more questions than answers. It does mean, however, that when we eventually return to these sites we will now know what further questions to ask and what particular features to put under scrutiny.

Enormous thanks to Sebastian and his colleagues at Hesdin, Olivier and his colleagues at Annevoie, Daniele and Sarah for their hospitality in Liege, Benoit at Modave and Hartmut and his colleague at Heidelberg and of course to Verna for some epic driving.