Voyages to the House of Diversion

Seventeenth-Century Water Gardens and the Birth of Modern Science

Thursday September 17th. Villa Farnese, Caprarola

Olivier and Isabelle were away early to get back to Rome and connect

with their flight home. Everyone was on board (two cars) for an

excursion to the great sixteenth-century garden at the Palazzo Farnese at Caprarola, a 45

minute drive to the south which took us looping past the impressive

city walls of Viterbo before climbing up the side of a mountain and

round the perimeter of the Lago di Vico before descending on

Caprarola. There is a massive parking area in front of the villa which

seemed oddly empty but we parked there anyway and paid our 5 Euros each

to go in. No visitor shop selling guidebooks, no café, little in way of

refreshments but at least we could potter round at our own pace. The

huge pentagonal palace echoed the shape of contemporary fortifications

but was also echoingly empty and despite ample frescoes felt cold and

hollow. The

villa was actually grafted onto a earlier incomplete fortification

begun in the first decade of the sixteenth century. The architect

Giacomo Barozzi de Vignola started work on the villa proper in 1559 and

continued until 1573

Then inevitable view of the palazzo fronting onto the main street of

the town, view looking north. Verna and Michael climb the ramp up

to the front door.

The interior circular courtyard and the famous circular stair, the

scala regia.

An indoor fountain in the formerly open loggia known as the hall of Hercules and used in summer as a dining room.

One exited to the gardens from the piano nobile (actually the third

floor) via a couple of bridges across a substantial moat. The initial

garden was strictly geometric but was backed by an impressive grotto

inhabited by decayed satyrs. Meegan discovered the tap that turned it

on and created a shower resembling heavy rain that dropped from the

ceiling. Even in the garden routes were tightly controlled and

were ushered out and up to the park leaving several important features

inaccessible. However, this was more than made up for by access to the

marvelous pavilion with its famous water chain. It was a fairly long

walk up and along the ridge that Caprarola is based on but there was

breeze and plenty of shade from the trees. Once at the top we began

examining in detail the technology of a complex series of basins and

fountains tracking down a multiplicity of taps and pipes and of

course photographing them all.

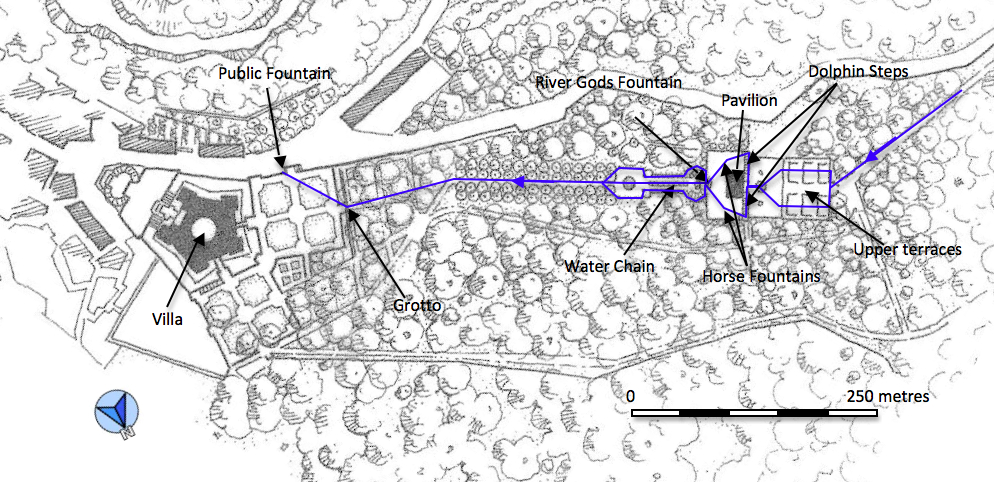

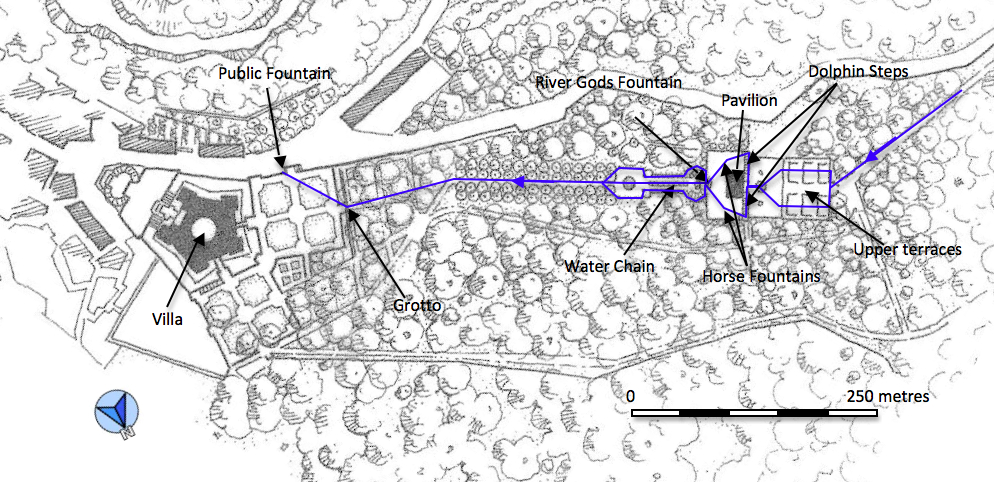

Speculative and schematic, some initial thoughts on the flow of water

through the garden, a day or so lifting manhole covers, of which there

are plenty, would suffice to plot this accurately

Grotto in the formal garden immediately west of the villa, view looking west.

Interior of the Grotto of the Satyrs with detail of an individual of particularly diabolical appearance.

The ramp up towards the upper part of the garden through the wooded park, looking west.

This is, of course, quite the wrong way to experience the garden,

when everything is working you start at the bottom and work up but

from a technical point of view it's easier to go with flow. Somewhere

way up the hill there must be a reservoir that takes the

water from a diverted stream or springs and sends it down to the

garden. First there are three low grassy terraces edged in stone with a

central path heading towards the pavilion. Water emerges at each level

from a set of grotesque masks, all different into a set of basins then

down to the next level. In front of (or maybe behind) the pavilion is

an elegant fountain but then the water is conducted down the

balustrades of two stairways flanking the pavilion passing the water

from spouting dolphin to basin to next spouting dolphin. Two lower

courts edged with Hermes and filled with box hedges cut slightly maze

wise contain small and rather decayed fountains of horses and dolphins.

These were sufficiently broken down to reveal not only details of

bronze pipe work but also the rather haphazard construction in brick

and tile that was normally hidden under a 5 cm thickness of stucco.

Particularly interesting were the nozzles emerging from the horses’

mouths (also seen on two unicorns above the staircase) which were in

copper alloy and letter box shaped supplying, no doubt, a suitably fan

shaped spray.

The upper limit of the formal

garden is marked by these pillars with niches,

The view looking down towards the casino or pavilion probably designed by

presumably the gaps were once

closed by gates, there is evidence of a conduit

Giacomo del Duca past terraces and fountain, looking south east.

coming into the garden just behind the left most

pillar, view looking north west

Detail of basins and terraces in the upper garden.

Two curving staircases descend to the next level starting behind a

massive vase supported by two colossal river gods bearing cornucopia

ending in spouts resembling the end of a watering can. The stairways were

lined with further grotesque faces spouting water into basins and there

was a large basin at the foot of the vase and river gods but what

catches the eye whether on the way up or down is the wonderful water

chain. This channel drops around 12 metres over a length of 50

metres and is supported around 80 cm clear of the ground on a series of

square pillars. The sculpted form of the channel, edged with fish but

profiled with shells and boat like shapes obviously was carefully

designed to achieve interesting patterns of flow and turbulence an

intriguing mix of the ordered and chaotic. The whole ends in another

large round basin with a rather underwhelming fountain clearly formed

so as not to distract from the water chain.

Retracing our steps down multiple ramps, an echo of yesterday’s

discovery at Bomarzo, we exited into a side street and after a bit of

fiddling about with cars ended up down the street at a rather

venerable, semi-subterranean restaurant specializing in fresh pasta and

mushrooms.

The end of it all, a small public fountain outside the garden.