A Twelfth Century Defensive Landscape

notes by Stephen Wass

Back to Fortifications Contents Page

Château Gaillard from SW

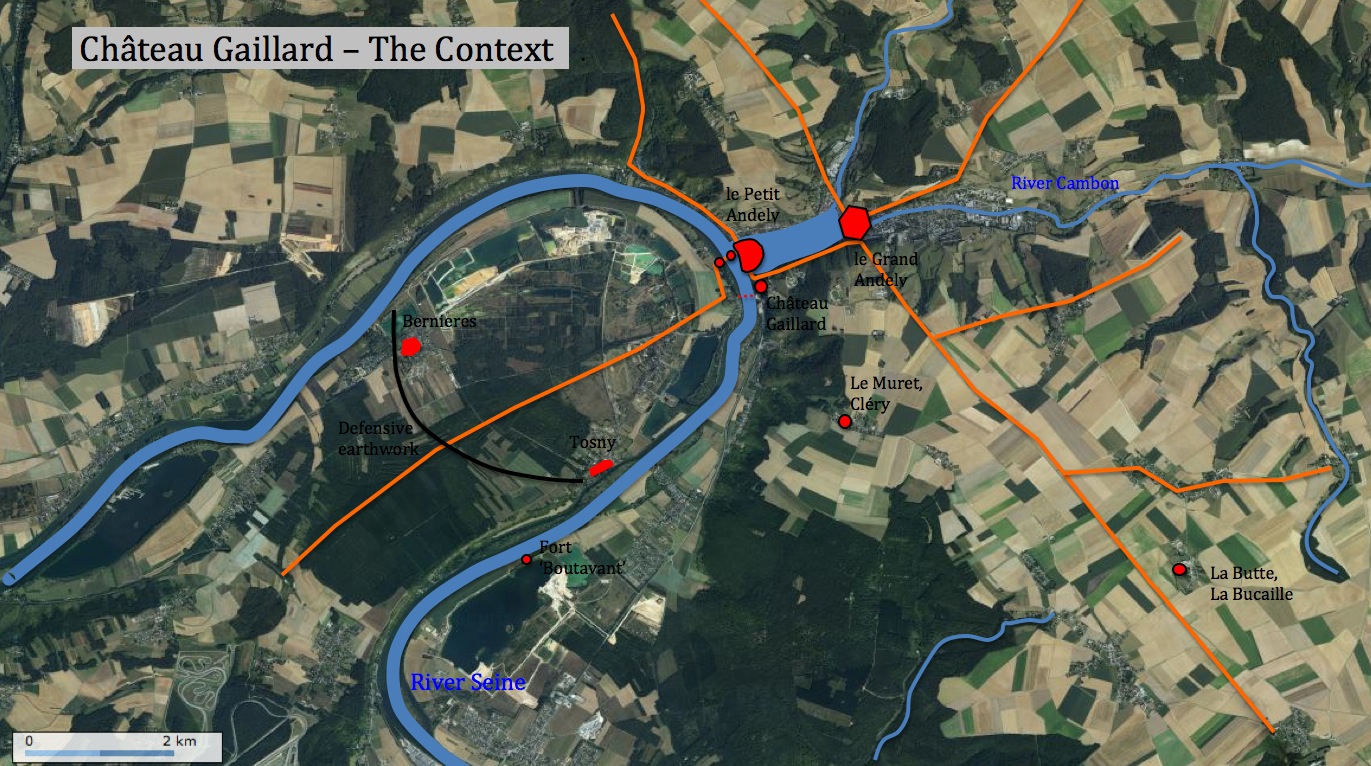

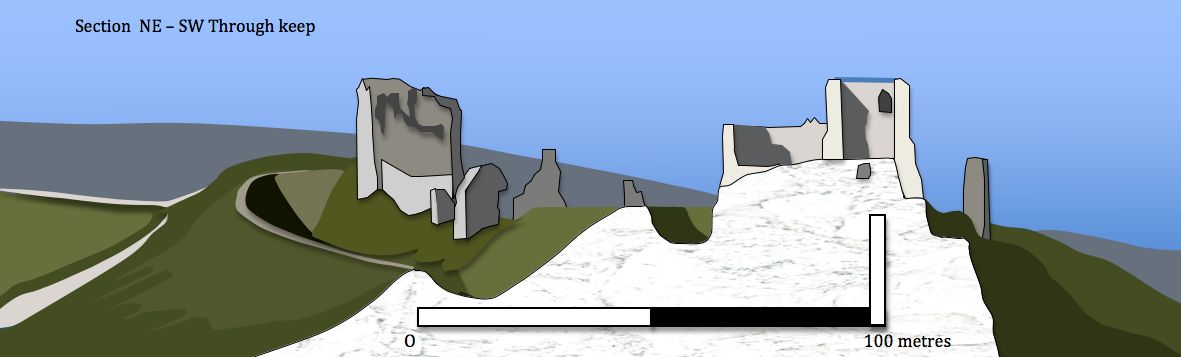

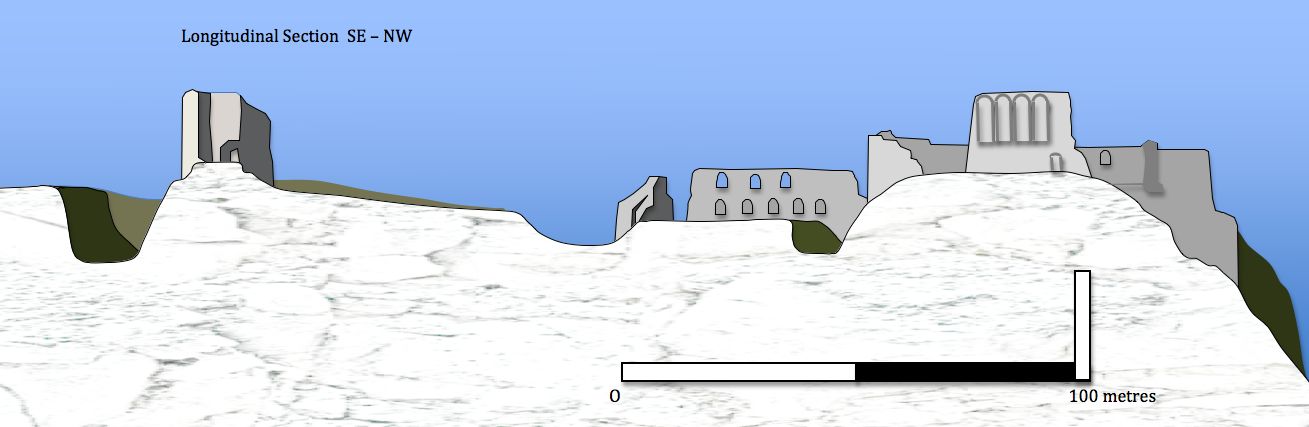

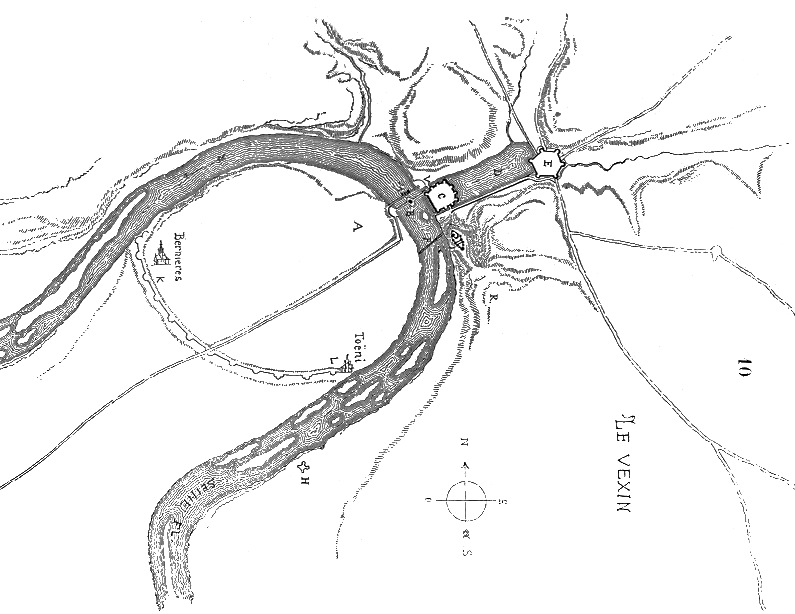

Many people will be familiar with the impressively sited Château Gaillard. This twelfth century fortress built by Richard I on a chalky cliff overlooking the Seine features in most standard texts on medieval castles. There is extensive coverage of its design, construction and fall but less is recorded about the landscape in which it lies and in particular the way in which elements within the landscape were manipulated to strengthen its defensive potential both strategically and tactically. By examining the outlying defences south of the Seine, the fortified village of le Petit Andely and town of le Grand Andely and a scattering of mottes to the south and east it should be possible to develop a better understanding of the castle and the its environment. The starting point is the remarkable engraving published in 1856 in the 'Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle' by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. This illustration with the accompanying text demonstrates a wider sensitivity to strategic issues, He describes the situation thus:

| "Les Français, par le traité qui suivit la conférence d'Issoudun, possédaient sur la rive gauche Vernon, Gaillon, Pacy-sur-Eure; sur la rive droite, Gisors, qui était une des places les plus fortes de cette partie de la France. Une armée dont les corps, réunis à Évreux, à Vernon et à Gisors, se seraient simultanément portés sur Rouen, le long de la Seine, en se faisant suivre d'une flottille, pouvait, en deux journées de marche, investir la capitale de la Normandie et s'approvisionner de toutes choses par la Seine. Planter une forteresse à cheval sur le fleuve, entre les deux places de Vernon et de Gisors, en face d'une presqu'île facile à garder, c'était intercepter la navigation du fleuve, couper les deux corps d'invasion, rendre leur communication avec Paris impossible, et les mettre dans la fâcheuse alternative d'être battus séparément avant d'arriver sous les murs de Rouen." |

Looking NW from the castle towards the Seine and le Petit Andely

"Here is how the Anglo-Norman king arranged all of these strategic defenses. At the end of the peninsula (A) the right bank of the Seine has eroded a series of very high rocky chalk cliffs which dominate the alluvial plain. On an island dividing the river (B), Richard initially raised strong octagonal tower with ditches and palisades, a wooden bridge passing through the gatehouse linked the two sides. At the end of the bridge (C), on the right bank, he built a wide beachhead protected by a wall that was soon filled with houses and took the name of Petit Andely. A pond, formed by withholding water from two streams (D), completely isolated the bridgehead. Great Andely (E), which existed before this work was also a fortified enclosure with ditches that are still visible and are filled by water from two streams. On a bluff over a hundred metres above the level of the Seine, and connected to the chalk hills by a thin strip of land on the south side, the main fortress was sited on the rocky promontory. At the bottom of the cliff, and connected to the castle, was a pier (F), consisting of three rows of piles, cutting across the Seine. This boom was further protected by palisaded structures established on the edge of the right bank and a wall and tower built on the hillside from the castle down to the river. Upstream a fort was built on the banks of the Seine (H) and assumed the name of Boutavant. The peninsula was defended at the gorge (K to L) and once garrisoned, it was impossible for an enemy to find the base camp on a furrowed field covered with huge rocks. The valley between the two Andelys was filled by the abundant waters of streams, controlled by the fortifications of the two towns located at each end. These were dominated by the fortress and could not be occupied nor could the slopes of the surrounding hills. These general provisions having been made with equal skill and promptitude, Richard devoted all his attention to the construction of the main fortress which was to command all defenses. Placed, as we said at the end of a promontory whose cliffs are very steep, it was accessible only through this strip of land that links it with the chalk high ground." Translation by S.Wass

It is unclear what his sources were for this map as by his time the vast pond between the two towns had been filled in and much of the town defences demolished. Of particular concern is the massive defensive line, presumably earthworks which ran in a great arc from 'Bernieres' to 'Toeni', where was his evidence for this? Of course much of it could have been obtained from early maps like the one below. and he may well have done field work in the area.

The strategic situation is also demonstrated well by the Cassini map of the eighteenth century depicting countryside which had changed little since medieval times. The local road network shows well as do the two fortified towns and the approach to the area over flat land to the south east. However, none of the ancillary works appear the great curving ditch which cut off the meander of the Seine was obviously not a significant feature of the landscape and the two mottes also to the south east are not indicated although their villages: Cléry and La Boucaille are shown.

The

references to outlying works connected to the main defensive works is

found in the 'Guide Historique - Château Gaillard' (Chlolet: Editions

Pays et Terrroirs 2006) by Marie M. Azard. She describes two

mottes which functioned as outworks or watch towers on the vulnerable

SE approach. The most important is known as 'La Boucaille' is in the

hamlet of Guiseniers around 5 kilometres SE of the Château. According

to Azard this consists of a 'vast pile of earth, now flattened

extending over a huge area surrounded by a deep ditch at that time

filled with water.' She also refers to the motte at Cléry, two

kilometres S of the chateau where there is a tree covered motte

surrounded by a water filled ditch.

All of the sites mentioned above have been plotted onto a recent aerial photograph of the area. From a research point of view I plan over the next year to visit each of these locations and document any remains that survive.

All of the sites mentioned above have been plotted onto a recent aerial photograph of the area. From a research point of view I plan over the next year to visit each of these locations and document any remains that survive.