| Weapons in Cropredy Church by Stephen Wass |  |

Assemblage as first seen in vestry cupboard Reproduction armour, south wall of south ailse

The weapons gathered together in the vestry cupboard are a curious assemblage consisting of one socketed bayonet, two spear heads and the remains of two small swords. These have been kept in the church since at least the 1930s1and were displayed in a tomb niche with civil war armour until it was stolen in the late eighties or early nineties at which point the remaining relics were removed to the vestry. One assumes that the rationale for keeping these weapons in the church was because of some association with the well documented Battle of Cropredy Bridge fought during the English Civil War on June 29th. 1644 2, however, as we shall see, this assumption is problematic with a number of the pieces.

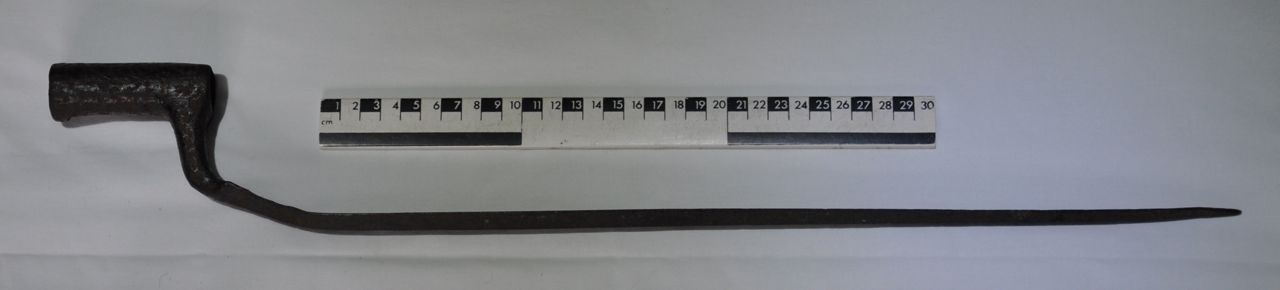

Cropredy Church Vestry (CCV) 11/1. Socketed Bayonet, Iron

| Clearly the bayonet is not a Civil War artefact. Initial examination of on-line sources 3

for socketed bayonets indicate a late eighteenth to mid-nineteenth century date however the bayonet has

a number of unusual features.

Firstly, unlike most military hardware of the period, the bayonet seems

devoid of any markings. It was generally the practice for

most pieces to carry a number of marks indicating information such as

by who, where and when they were manufactured and where and by who they

were deployed. Although there is considerable surface pitting due to

corrosion it does not seem sufficient to have removed all trace of such

stamps. The

arrangement for the majority of socketed bayonets seems for there to

have been a slot along the side of the socket, generally 'L' shaped, to

facilitate fixing the bayonet to the muzzle. This feature is

absent. A thickening of the rim to the right hand of the

rear of the socket (looking towards the point) has a notch cut out of

it possibly to engage with a feature known as a Lovell catch. Other

curious elements include strange cranking effect at the shoulder of the

bayonet. In virtually all examples of British bayonets the arm which

joins the socket to the blade leaves the socket at close to right angle

and then bends through another right angle leaving the blade lying

parallel to the barrel. Some waving to the edge of the triangular

sectioned blade suggests bending at the second angle but the whole

arrangement appears to be non-standard. In addition the overall length

of the blade at around 485 mm is longer than most British bayonets all

of which suggests that the item may be of continental or colonial

manufacture. Given the number of distinctive features it should be

possible to identify the origins of the bayonet but this would still

beg the question of how it came to be deposited in Cropredy church. |

CCV 11/2 Large Spear Head - Iron

This large iron spear head is heavily corroded. There is a jagged break at the socket end and the whole blade is bent in a curve suggestive of damage within the ploughsoil. The triangular blade returns quite sharply with straight sloping shoulders to the socket. In section the blade is diamond shaped with a central ridge being prominent on both faces. The form of this piece seems much more closely related to medieval and earlier patterns than to later pikes which were used in the seventeenth century as illustrated on the Royal Armouries web-site 4, however, one has to acknowledge that during the Civil War all manner of weapons were pressed into service and the use of earlier weapons and armour must have been common, at least at the outset 5.

CCV 11/3 Spear Head - Iron

s

| The

second spearhead is also of iron, smaller in size and significantly

less corroded. The split socket is complete and has a pair of small

holes near the base through which nails could be inserted to secure the

haft. The shoulders curve in as they approach the shaft and again the

blade has a medial ridge on both faces although the diamond effect in

section is much less pronounced. Spear heads of this type are common

across many periods and cultures and in the absence of any specific

context it is hard to assign this weapon to the mid-seventeenth

century. A common arrangement for pike heads was to extend the sides of

the socket further down the pole to prevent the head being cut off

during combat. obviously no such feature is present here |

Small Swords.

The assemblage contains two heavily damaged small swords both of iron, comparatively crudely made and both devoid of any maker's marks. In both cases the organic elements which made up the hilt are absent, presumably being long decayed. In addition both swords show evidence of reuse subsequent to being employed as fighting weapons. The small sword is defined as 'a personal dueling tool and weapon of self defence' 6. It became recognised towards the middle of the seventeenth century and particularly popular through the eighteenth century when many fine examples were produced. An early instance exists dated 1651 and said to belong to Major General Charles Worsley, a parliamentarian commander, appointed Major General for Lancashire, Cheshire and Staffordshire in 1655 7. The structure of the hilt and guard was fairly standardised and consisted of a clam shell guard, generally shaped like a figure of eight. Behind this were a pair of circular finger guards and then a rudimentary cross piece or quillion. One end of this was curved round and upwards to form a knuckle guard until it met the rounded pommel above the hand grip. Small swords were generally between 800 and 900 mm in length, triangular in section and only sharpened at the point.

CCV 11/4 Small Sword - Iron

This

is the more complete of the two swords. It has lost the hilt and pommel

but the other metal work although slightly pitted is complete and

fairly well preserved. The clamshell guard is a separate piece to the

single section comprising the finger guards, quillion and knuckle guard

and both can readily be detached from the blade by sliding them off the

rectangular section tang. The present length of the blade is just 380

mm and it has clearly been rather crudely shortened and reground at

some time. The knuckle guard terminates in a decorative feature like a

bird's head whilst the quillion has a tear drop shaped terminal which

has been strongly bent to one side. The socket that takes the tang of

the blade swells bulbously towards a rectangular fitting which

slots into the shell guard.

CCV 11/5 Small Sword - Iron

| The

second small sword exhibits several differences. The blade is unusually

flat in section and the surviving portion is around 400 mm long. Severe

bending of the blade at two points indicates the blade snapped when

being used as a lever. The shell guard and finger rings and quillion

remain firmly attached as at some point a large hand made round headed

nail has been driven in between the tang and the socket in the hilt.

The finger rings appear flatter than is the case with CCV 11/4 although

this may be the result of later damage. The knuckle guard has snapped

away entirely. The upper end of the tang is bent over in a sharp curve

to approximately 90 degrees. The nail and the adjacent tang bear traces

of a shiny black paint. |

CCV 11/6 'Cannon Balls' a and b Cast Iron, c and d Stone

These were removed separately from a drawer in a cupboard in the vestry and had presumably been displayed at some time alongside the armour and weapons. The heaviest, CCV 11/6a is of iron, quite deeply pitted and with a diameter of 60 mm ( 2 3/8 inches) and weighs 905 g (1lb 15 3/4 oz). The second iron ball, CCV 11/6b has a smoother surface with the same diameter of 60 mm ( 2 3/8 inches ) but is lighter in weight at 845g (1 lb 13 3/4 oz ). the larger of the two stone balls weighs 92 grams (3 1/4 oz ) with a diameter of 42 mm ( 1 5/8 inches) and is made from a what appears to be a mid-brown fine grained sandstone. The smallest ball is 35 mm in diameter (1 3/8 inches) and weighs 50g ( 1 3/4 oz ). This has a coarser finish except for a flattened circular patch 14mm across which is quite highly polished. The stone appears to be a brownish grey limestone.

Artillery prior to early 1700's was frequently subject to some variability. Using slightly earlier terminology the two larger iron balls best match the gun known in the sixteenth century as the falcon with a calibre of 2 1/2 inches and a shot weight of 2 pounds 8. There is a considerable database of cannon balls recovered as part of the Portable Antiquities scheme, a ball of 2 1/2 pounds with a calibre of 2 1/2 inches from Penistone Church, South Yorkshire is listed as 'probably for the type of light cannon known as a falcon, dating from 1600-1800 AD'. A similar item from North Ferriby in East Yorkshire is described thus:

'An iron

cannon ball probably dating from the Post Medieval period. At 883g

(1lb, 15oz) and a diameter of 62mm (2.4in) this was almost certainly

used with a Falcon Cannon which had a bore of 2.5 inches and took a ball of

2lb. The cannon ball is rusted and has a flaking surface but is

otherwise in good condition. These cannon were developed in the late

15th century, but continued to be used into the modern period. It

probably dates from the 16th or 17th century, but could be later.' 9

These light weight guns were used to cover the gaps between infantry units and were very portable on the battlefield. During the course of the battle the Royalists captured a number of Parliamentarian guns:

'whereof 11 Brasse; viz 5 sakers, 1 Twelve pound Peece, 1 Demiculverin, 2 Mynions, 2 Three pound Peeces & c. besides Two Blinders for Muskets and Leather Guns' 10 however, none of these specifically match our two examples a and b. In another account of the action, '... their cannon all which (beeing Eleavon peeces ) were then taken, & 2 Barricadoes of wood drawen with wheeles in each 7 small brasse & leather Gunns charged with case shot.' 11 The reference to leather guns is interesting and refers to a light weight piece in which, ' a copper or white iron tube wrapped around with rope and sewn into a leather case' 12 was employed. The smaller balls, c and d are larger than the normal calibre for civil war muskets, which ranged from half to three quarters of an inch, but could possibly have come from one of these smaller pieces of field artillery. A similarly lightweight piece was the robinet whcih had a calibre of around 1 1/2 inches 13. Reconstructed examples of this kind of gun can be seen in action served by Sir Thomas Glemham's Artillery Company 14.

Two other cannon balls from the area are held by the Oxfordshire Museums Service. One ( OXCMS: 1974.28.622) was discovered in the nineteenth century near Cropredy Bridge, it has a diameter of 90mm and the record suggests it was fired from a saker or drake cannon. The second ( OXCMS:2003.150 ) is from Little Bourton and has a diameter of 70 mm and weighs 3 lb 15.

Four other iron cannon balls from the county are recorded. One from the site of Banbury Castle ( OXCMS: 1978.121.1 ) has a diameter of around 45 mm and another small example with a diameter of 55 mm ( OXCMS : 1975.160.867 )

came from Wantage. The remaining two are larger. An example from Longwall Street, Oxford ( OXCMS : 1985.174.1 ) has a diameter of 90 mm but its description as being a 'one pound cannon ball' is almost certainly incorrect whilst the other from Ardley ( OXCMS : 1976.432.1 ) has a diameter of around 130 mm, no weight is recorded. Given the comparatively small number of cannon balls recorded for the county the examples from Croprdy Church could be a significant addition to the corpus.

CCV 11/7 Spear - Iron head, wooden shaft

This intact weapon has a broad flat iron leaf shaped head with some medial thickening. The socket clasps the end of the shaft and is projected downwards in two parallel strips clearly designed to stop the head being hacked off the shaft. This is secured in place by three small iron nails on each side. The overall length of the weapon is 2510 mm ( 99 inches or 8 foot 3 inches ), although there has been some decay to the butt of the shaft and so it may have been longer originally. The wooden shaft tapers markedly along its length, the approximate diameter is 20 mm ( 13/16 inch ) just below the head and 31 mm ( 1 1/4 inches) just above the butt. Roughly half way along the shaft there is clear marking of some kind of jointing although it is not possible to say exactly how this is arranged without taking it apart.

To complete the picture there are two modern 'practice' pikes in the chuch, one is propped up in the corner of the ringing floor of the bell tower and the other is in the attic above the vestry. Presumably these were either donated to us or simply abandoned by contemporary groups of re-enactors who visited the church.

Conclusion.

One wonders how many other parish churches close to Civil War battle sites hold similar collections of 'relics'. It would be a productive topic to research in order to throw some additional light on themes of conflict and remembrance in the English church. The greatest present difficulty with the assemblage is our inability to establish provenance for any of the items. The assumption has been that these artefacts were recovered form the battlefield. This clearly cannot be the case for the bayonet whose presence must call into question the origins of the other pieces. The spear heads may not belong to the period at all whilst the small swords both seem to have been adapted for post combat use and may even have been employed in a domestic context: as pokers or skewers perhaps. Ideally we need to find a written account which describes the circumstances of the finding and deposition of one or more of the pieces to make a secure link between these finds and the momentous events of 1644.

References

1. Les Underdown - personal communication 3.2.11

2. Margaret Toynbee and Peter Young. Cropredy Bridge , 1644 The Campaign and Battle Kineton, The Roundwood Press 1970

3. British Socket Bayonets at: http://jeffreyhayes.com/bayonets/British%20Sockets.htm

Socket bayonets of the World at: http://www.old-smithy.info/bayonets/Socket_Bayonet.htm

4. Royal Armouries On-line Collection - search for 'Pike' : http://collections.royalarmouries.org/index.php?a=wordsearch&s=gallery&w=pike&go=GO

5. Peter Harrington English Civil War Archaeology London, Batsford/English Heritage 2005 pp. 111 - 112

6. The Association for Renaissance Marshal Arts - Medieval and Renaissance Sword Forms at: http://www.thearma.org/terms4.htm

7. Can be seen at: http://www.heritage-images.com/Preview/PreviewPage.aspx?id=1196914&licenseType=RM&from=search&back=1196914&orntn=1

8. Albert C. Manucy Artillery Through the Ages Washington D.C. National Parks Service 1949 p. 35 Available on-line at:

http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=yYupSOK0BgIC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

9. The Portable Antiquities Scheme search for cannon ball and post-medieval at: http://www.finds.org.uk/database/search/results/objecttype/cannon+ball/broadperiod/POST+MEDIEVAL